.jpg) |

| photo: Joe Mazza Brave-Lux |

Born in Tijuana, Mexico, and now living near Chicago, Luis Alberto Urrea is a Mexican-American author whose novels include The Hummingbird's Daughter, Into the Beautiful North and Queen of America. His nonfiction The Devil's Highway was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. His latest novel, The House of Broken Angels (Little, Brown, $27; reviewed below), focuses on a modern Mexican-American family in San Diego.

You have written some extraordinary books, both fiction and nonfiction, about the Mexican-American experience, but The House of Broken Angels seems to be your most personal work in capturing multicultural family life in modern America.

You are dead-on. Sometimes you feel like you're writing with your own blood and sometimes, as Jim Harrison told me, God hands you your novel. The way in which my big brother died two years ago was very much reflected in the process of mortality in The House of Broken Angels. What struck me at the time was how much a celebration of one man's life it was. How a single working-class dad changed the world in his own small way. And, of course, that "small way" was in every way epic. So the novel is a hymn to our daily lives, how sacred they truly are. Finally, the tone of the recent presidential election made me know I had to speak up for the de La Cruz family.

The interplay between "Big Angel" de La Cruz and his half-brother "Little Angel" is so funny and heartwarming. Little Angel is half-gringo, and this lends itself to an examination of white culture versus Latinx culture. Is this tension between the two cultures something you experience in your own life, and, if so, how do you navigate it as a writer?

Of course, I experience this. It's the gift that keeps on giving. I'm not looking so much at an examination of white culture versus Latinx culture as an examination of American culture. In the age of the president fantasizing about "bad hombres" and hordes of Mexican rapists, I am examining what it means to be an American. With a Latinx last name, things turn political on you whether you want them to or not. It has all made me very aware of the human border that divides every kind of people, sometimes from each other. The great Rudolfo Anaya once told me that if I could make my Tijuana grandmother the grandmother of a reader in Iowa, that I would have committed the most profound political and theological act through my art. I took it to heart and have never stopped trying to foist my abuelita on readers.

You touch on generational differences in your novel, differences between foreign-born immigrants trying to assimilate and first-generation offspring of immigrants trying to create their own identities. But there's also a sense of reconciliation at the end.

I believe every family has its own code, has its own negotiation with this identity issue. Some want to preserve the homeland in the heart at all costs. Some need to negotiate the tides of change and embarrassment and even shame. I don't believe there is a blanket answer. It's profoundly personal. My own father was terrified that I would lose my Mexican-ness. My North American mother was terrified that I would lose my American-ness. Why do I write about the border? Because it is right here, inside each one of us. I could not prescribe an answer to any family, except what I am ultimately preaching in my book. As Big Angel tells his daughter: "All we do, mija, is love. Love is the answer. Nothing stops it. Not borders. Not death."

As Big Angel's health declines, his daughter Minnie takes over many important roles in the family that the sons seem incapable of handling. Is this just her character and strong-mindedness or is there a more deliberate feminist angle at play? Perhaps a subtle critique of the machismo of the past?

As Big Angel's health declines, his daughter Minnie takes over many important roles in the family that the sons seem incapable of handling. Is this just her character and strong-mindedness or is there a more deliberate feminist angle at play? Perhaps a subtle critique of the machismo of the past?

There is always a tweaking of machismo in my books. See The Hummingbird's Daughter or Into the Beautiful North. Strong women raised me, often in the absence of the men. So I do see a very strong matriarchal thread. It takes the "Americanized" Little Angel to make the case to his brother about the new matriarch in the family who can take his place.

The House of Broken Angels arrives in contentious political times. Your novel humanizes not only Mexican-Americans already in the country but the act of immigration and the challenges of transnational life. What do you think Americans need to know about Latin America and immigration that they're just not getting?

That question encapsulates my entire writing career. Not only my work, but my life. My readers know that I have been railing against dehumanization of any kind in every book. It's very easy to look up statistics about what your food would cost if the farmworker wasn't picking it. It's very easy to look up the actual immigration laws and make up your own mind. The American people need to be reminded that the marginalization of the other is the crime. It's a pernicious and dangerous crime. I believe in grace. But I also believe a little touch of honesty might help save the world.

In The House of Broken Angels, Big Angel is coming to terms with his own death, yet there is such magic and beauty and romance surrounding the event. Do you feel you belong to the tradition of magical realism in Latin American literature? How does your writing style reflect your worldview?

I love this question! I think all my writing reflects my worldview, yes. As far as magical realism goes, I'm not sure what to say about that. I do not consider myself a magical realist. And García Márquez himself said he essentially stole William Faulkner's vibe. I can tell you that being raised with a few million Mexican relatives means that one witnesses things and hears stories that might not be in the usual curriculum. Everybody believes in ghosts, miracles, apparitions, hauntings. I was told my aunt could fly. Nobody questioned it. And I don't think that this is limited to being Mexican. I am sure any Irish reader knows exactly what I am talking about. Chinese readers know exactly what I am talking about. The world is alive with a kind of magic if we only had the eyes to see. Sometimes the wonders are quite subtle, perhaps a kiss on a dying brother's forehead. But if we are paying attention, those small kisses are absolutely vast and heartbreaking. --Scott Neuffer

Luis Alberto Urrea: An Epic American Dream

Then, after the film was announced, I read A Wrinkle in Time aloud to my four-year-old. As I reread, many of my original sentiments were reaffirmed: the creatures on Ixchel are strange (though I now appreciate Aunt Beast's care for Meg) and I'm still totally fine with never experiencing fifth dimension travel. Ever.

Then, after the film was announced, I read A Wrinkle in Time aloud to my four-year-old. As I reread, many of my original sentiments were reaffirmed: the creatures on Ixchel are strange (though I now appreciate Aunt Beast's care for Meg) and I'm still totally fine with never experiencing fifth dimension travel. Ever.

.jpg)

As Big Angel's health declines, his daughter Minnie takes over many important roles in the family that the sons seem incapable of handling. Is this just her character and strong-mindedness or is there a more deliberate feminist angle at play? Perhaps a subtle critique of the machismo of the past?

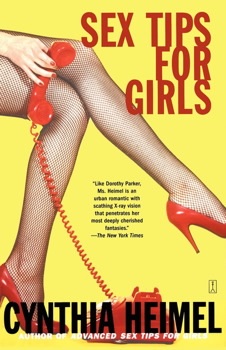

As Big Angel's health declines, his daughter Minnie takes over many important roles in the family that the sons seem incapable of handling. Is this just her character and strong-mindedness or is there a more deliberate feminist angle at play? Perhaps a subtle critique of the machismo of the past?  Feminist humor columnist, playwright, television writer and author Cynthia Heimel died on February 25 at age 70. She began her writing career in the late '60s at Distant Drummer, a counterculture magazine in Philadelphia, before moving to the SoHo Weekly News, New York magazine, then the New York Daily News. She published her first book in 1983, Sex Tips for Girls, which mixed satirical takes on popular women's magazines like Cosmopolitan with actual feminist sex advice. Heimel later had columns in the Village Voice, Vogue and Playboy, of all places, the first one about women by a woman (it ran until 2000). She wrote A Girl's Guide to Chaos, a play that later became a book, in 1986. Heimel eventually moved to Los Angeles to write for the TV series Kate & Allie and Dear John.

Feminist humor columnist, playwright, television writer and author Cynthia Heimel died on February 25 at age 70. She began her writing career in the late '60s at Distant Drummer, a counterculture magazine in Philadelphia, before moving to the SoHo Weekly News, New York magazine, then the New York Daily News. She published her first book in 1983, Sex Tips for Girls, which mixed satirical takes on popular women's magazines like Cosmopolitan with actual feminist sex advice. Heimel later had columns in the Village Voice, Vogue and Playboy, of all places, the first one about women by a woman (it ran until 2000). She wrote A Girl's Guide to Chaos, a play that later became a book, in 1986. Heimel eventually moved to Los Angeles to write for the TV series Kate & Allie and Dear John.