|

|

| photo: John Coutts | |

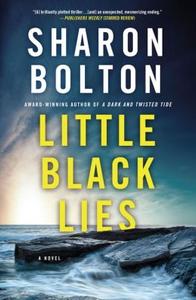

Sharon Bolton is the author of seven mystery novels, including the Lacy Flint series. She lives and writes in England, though her latest book, Little Black Lies (reviewed below), is set in the Falkland Islands. The standalone novel centers on three people who have all confessed to the same crime: kidnapping and killing a local boy, the latest in what is believed to be a string of missing children.

Little Black Lies is a complicated novel, weaving together several mysteries in one. Can you summarize it?

On a fundamental level, it's about three friends whose lives have been torn apart by tragedy, and how they manage to find their way home. Not in a literal sense, but metaphorically, as they get back to a place where they can be whole again as people in their own right, and where they can, to the extent possible, rebuild the relationships they used to have.

It is also about people who live in a very isolated community, and the impact that that isolation and smallness can have upon a society, especially when something goes wrong.

And as a mystery novel, I was intrigued by the idea of three people confessing to the same crime, when two of them have to be lying. Why would they do that? How could that happen?

You chose to set Little Black Lies in the Falkland Islands, in the very small town of Stanley. What prompted this?

I particularly love isolated communities and island communities, because there's that sense that when the sun goes down and the planes stop flying, there's no way to escape and nowhere to go. I love that claustrophobic feeling, and it works very well in mysteries.

I feel very strongly that I am a writer of British mysteries, and my stories have got to be set in the British Isles among British people, because that's what I know and that's what I do and that's where I get my inspiration. But all the islands around Britain have been done to death by other crime writers. I've done them myself; my novel Sacrifice is set on the Shetland Islands off the coast of Scotland.

Then someone suggested to me: What about the Falkland Islands?

They are British islands. They're inhabited by people who believe themselves to be British and who want to remain British. I was struck by the dichotomy between the familiarity of the British setting and the exoticness of it being so far away, just off the coast of South America.

It wasn't possible to do a research visit, but I very much intend to go as soon as possible.

I don't believe it's necessary to visit a place to capture its spirit. I did a huge amount of desk research. I ordered and read every book on the Falkland Islands that I could find. I looked at maps, I looked at photographs.

It's a lot easier now than it might have been 10 years ago, because many people on the islands are heavily into social media. Lots of people there have blogs that I was able to follow, they're on Twitter, they have Facebook pages. There are all these innocent people on the Falkland Islands with no idea that I've been stalking them online.

But it gave me a very, very strong feeling of the place. I immersed myself with the desk-space research, wrote the book, and then was lucky enough to find three people who have lived there and know the islands well, and they read the book and pointed out mistakes and told me where I got it wrong.

You've said before that you are "compelled to imagine how [life] can go wrong." How is Little Black Lies an exploration of that?

Quite a few years ago, I was chatting with a woman in the village where I lived, and I asked her if she had any children. She physically recoiled from me. And I thought, "What on earth have I done?" Later I found out that some years earlier her husband and her two children had been killed in a car accident, and her life had never been the same again. That struck me quite hard, the idea of someone who has to go on when their life has been taken away.

And then there was a serious road traffic accident very close to where I live. A woman had been driving a carload of children home from a party, and something had gone horribly wrong on that journey home and she crashed the car. She survived, but several of the children died. How on earth do you live with that?

So these two things were in my head and I put them together: What if the one woman was best friends with the other? How would that play out?

That was the start of it. But because it speaks so deeply to what, as a parent, are my worst fears, that something might happen to my own child or to children in my care, it was a very personal--and at times quite distressing--experience to write.

What was it like to write the book in three distinct parts, switching perspectives between each part and weaving those back together?

It had to be that way because of the original idea of the story, with three people all confessing to the same crime. They each had to have an equal share and point of view in the narrative to enable the reader to get inside their heads, to understand why they are the way they are, where they're coming from, what's driving them and what they're capable of.

Writing the same scene twice from different perspectives was quite tricky, but I did get a lot of satisfaction from it. It was interesting to show how two characters can react very differently to the same thing.

There's so much guilt and so much grief in this book and for all three characters.

What I found very interesting as I was writing this was the question of which is worse: guilt or grief?

I particularly liked the link I was able to make with the poem, "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner." I loved, in a very dark way, this idea of this rotting carcass being hung around someone's neck, and them having to carry it with them throughout life. In many ways, all three of the main characters have that thing around their neck, and they have to learn how to throw it off in order to live properly again.

Would you say that that guilt and grief pushes the characters to act outside of what we'd normally consider "right" and "wrong?" Into the grey area between the two?

I think it's possible to understand actions even if you can't condone them. I suppose I was exploring, to some extent, how far people can go. We never really know what we're capable of until we're put to the test. And luckily most of us never are. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm