|

|

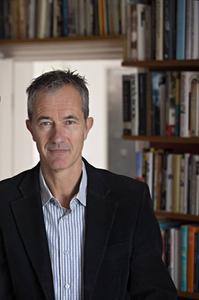

| photo: Matt Stuart | |

A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Geoff Dyer has received the Somerset Maugham Award, the E.M. Forster Award, a Lannan Literary Fellowship, a National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism and, in 2015, the Windham Campbell Prize for nonfiction. The author of four novels and nine works of nonfiction, Dyer is writer-in-residence at the University of Southern California and lives in Los Angeles. His books have been translated into 24 languages. White Sands: Experiences from the Outside World (Pantheon, May 2016) is his newest collection.

With his trademark wit, Dyer examines a host of seemingly unrelated landscapes across the globe: Tahiti, where he is in search of himself searching for Gaugin; the Forbidden City in the impersonal sprawl of Beijing; an obscure land art project in remote New Mexico; from Oslo north into Svalbard's endless dark; points across the great American West and, finally, Los Angeles.

Was there any rhyme or reason in choosing the locations you ended up traveling to?

It was pretty random, but they were all places I'd been wanting to go to for one reason or another. And then I thought there might be something about the Adorno house and Watts Towers that would fit in thematically with other stuff in the book--and after I'd been to these places I saw that they also knitted up or provided some kind of resolution of those themes.

So much of this book seems to be about traveling, focusing on interludes of waiting, wondering, on long thoughts that depart from a place and, rather than return back to where you started, lead us somewhere new. Did you feel at times that you were writing about a writer traveling?

I just felt like a writer writing--which is a form of travel, I suppose. But maybe I should qualify that further: most of the time I felt like a writer having trouble writing--which is a writer not getting anywhere.

At one point, you acknowledge that you are essentially a British intellectual author in Tahiti complaining about Gauguin complaining about Tahiti, an irony you seem fully aware of and embrace. Are these the facets you set out to discover?

It just ended up that way. I was really excited about going to Tahiti and I loved Gauguin--and then the experience of being there started sucking so I had to make some kind of accommodation with the suck. Humor is the natural aid to and result of that accommodation. Naturally these sentences could be re-written to be about (or read as an allegory of) England--minus the initial excitement. Which is a way of saying it started that way, too.

Were there any destinations on the agenda that went unexplored--trips that you originally thought were going to be part of White Sands but didn't make the cut?

I went to a number of places hoping there might be something there writing-wise--either a vibe the landscape was giving off or some kind of adventure that might befall me--but in many cases it didn't happen. Strangely, I'm now having trouble remembering where they were, but I promise I regularly came back empty-handed. Regarding Gauguin in French Polynesia, you say "our (historically constructed) idea of paradise is, precisely, a place untouched by history." Later, you trace the German philosopher Theodor Adorno's emigration to Los Angeles during World War II. In his book Minima Moralia, one of the things Adorno found most striking about the American southwest was the "absence of historical memories" in the landscape. This was an interesting parallel, between where you begin and end in White Sands--the notion of the pre- and post-historical landscape, and how neither were what those giants of their time expected. Nothing is ever what we suspect, which is a thought that appears time and again in White Sands.

Regarding Gauguin in French Polynesia, you say "our (historically constructed) idea of paradise is, precisely, a place untouched by history." Later, you trace the German philosopher Theodor Adorno's emigration to Los Angeles during World War II. In his book Minima Moralia, one of the things Adorno found most striking about the American southwest was the "absence of historical memories" in the landscape. This was an interesting parallel, between where you begin and end in White Sands--the notion of the pre- and post-historical landscape, and how neither were what those giants of their time expected. Nothing is ever what we suspect, which is a thought that appears time and again in White Sands.

That's an interesting connection you've spotted--and one that had escaped me. One of the interesting things about L.A., though--the exemplary city without a past--is how much past, how much history, there is here. The Adorno house is proof of that. It's really nice that L.A. is not semi-pickled in and by history the way that England is. On the other hand, when events are unfolding somewhere on the world stage, one often feels removed from them by virtue of being on the west coast of America--partly because of the time difference. In London, you feel much closer to the heart of what's going on in the world--unless it's something happening in California, of course. L.A. is very well placed for that.

You intersperse chapters set across the globe from each other with vignettes about small, folkloric places from your childhood in Cheltenham, England. What did traveling to exotic, storied locations reveal to you about your own "island no bigger than a back garden?"

I guess the purpose of those chapters--and this is an answer to your question--is to try to show how the seeds of the exotic elsewhere (or at least of my attraction to and appreciation of them) were actually planted back in England in the deeply un-exotic soil of childhood. Let's say they are buried there, in the unconscious. Those little chapters unearth them.

Your writing tends to deconstruct moments from different points of view (Li's photographs in "Forbidden City"). Whether something is beautiful, awkward, thought-provoking, meaningless or sad, you spend large amounts of time trying to get to the various forms of resonant, abstract truths. Rarely in whole, usually in part. What is to be learned there?

The only word I would quibble with in this is "abstract." I think the truths I am drawn to and try to articulate are often physical or embodied--or embedded. They tend also to be incidental in the sense that they grow out of incidents. To that extent I am--and I think this is the only time I've ever said this--a storyteller, albeit one like the hitchhiker in White Sands who, as the narrator of that story says, is not a very good storyteller because he's always bringing in all sorts of irrelevant detail, slowing things down, etc.--exactly as you say.

"You realize that this is not a piece of art to be seen but--the point bears repeating--an experience of space that unfolds over time." It often feels that you are casually going after the bigger fish, even if you insist that certain inquiries prove useless.

Strangely, the idea of "story" comes up again here. There's a certain amount of cataloguing, but it tends to be sequential, as in any story. It's somewhat frustrating to me that the book is always being described as a book of essays; it's as much a book of stories. Even if the fish is big you need a net with a fine mesh. Or something to hook the reader's attention.

I came away from White Sands thinking about what we use landscapes to discover. If there was ever any one notion uniting your various episodes in this book, I think it's your ruminating on this idea, returning again to ask the same questions and ending up with new answers each time.

Yes, I think that's a good summing up. It's why I was tempted to use that painting by Vedder, of the pilgrim at the Sphinx, on the cover of the book, sort of listening to it, hoping to have its mysteries revealed. This observation of yours also brings me back to that amazing passage in the book--don't worry, I'm not about to lay some major ego trip on you!--quoted from Raymond Williams's The Country and the City, where he takes something that we are very used to seeing (the English stately home) and by asking us to think about it in a different way--"think it through as labour"--causes us to view it in a fundamentally different, more complex way. It's also a reminder of how much of the landscape is man-made, historied, a result of social forces that are still actively engaged in shaping it. --Jarret Middleton, author/freelance editor