|

|

| photo: Julie Soefer | |

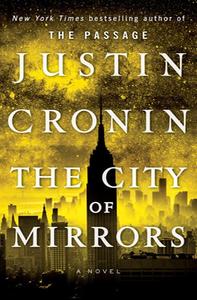

The final volume in Justin Cronin's acclaimed Passage trilogy has just been released. The City of Mirrors (Ballantine) finishes the dystopian, near-future "vampire virus" story that began with the The Passage and continued through The Twelve. Cronin's trilogy stands as a major work of American imaginative fiction that in addition to hitting the sweet spots of vampire and end-of-the-world novels, also has quite profound things to say about the human race's capacity for self-destruction, redemption and sacrificial love. Our review is below.

You've just completed an acclaimed trilogy that spans 2,400 pages and took almost a decade to write. What were your feelings when you completed the trilogy? What has the journey been like for you?

Mostly I feel stunned. Has it really been 10 years? Did I just write 900,000 words? To be honest, it's all a little disorienting. A story that has occupied at least half my brain, waking and sleeping, for a decade is suddenly gone from my thoughts, at least creatively, because it's fixed in place. A lot of people tell me I should be celebrating, but the feeling is not at all like, say, finishing your final exams and jetting off to Cabo. It's more solemn than that, like standing on the pier and watching friends sail away.

What was your writing routine during that decade?

I tend to separate my creative time from my actual writing time. Most of the creative work for the trilogy was accomplished while I was running or, in the last few years, swimming. Under the auto-hypnotic effect of some rhythmic, physical activity, my mind does its best work. Generally I try to be at my desk for five or six hours in the middle of the day; then I get some exercise, preparing for the next day's work. When I'm close to the end of a draft, my workdays expand, sometimes to as much as 12 hours, but as I've gotten older (I'm 53), I've mellowed a bit. If I'm tired, I'm tired; no use forcing it. There's always tomorrow.

Even though The Passage is a work of fantastic literature, there is a very specific and grounded nature to the geographical and technical aspects of the novels. How much research did you do and what is your approach to research?

I do a great deal of research, some of it via the Internet, some of it by consulting people who know things I don't, some of it through less formal, more ambient means--by, say, visiting a place I intend to use in the novel and drinking in its textures. Research was an exceptionally fun part of writing the trilogy, dipping into fields of study that, at the outset, I knew nothing about at all.

You completed the first volume before dystopias were such a hot genre. Why do you think dystopias are so popular these days? What needs do these books satisfy?

Many people say it has something to do with global warming, or terrorism, or political dysfunction--all pressing matters of the day--but I disagree. The world is in trouble, but it's actually been in substantially worse trouble before, and by this I mean during the Cold War, when it seemed entirely possible that humanity was going to incinerate itself in the next 40 minutes. Our interest in dystopias and end-of-the-world stories is as old as human civilization; we just shape these works to fit the anxieties of the moment. The apocalyptic novels I read as a kid in the '70s all pretty much focused on nuclear annihilation. The danger posed by 10,000 nuclear weapons pointed at 10,000 other nuclear weapons pretty much trumped every other danger in the history of the civilized world. Since the Cold War ended, though, and especially since 9/11, the threats have been less clearly defined, leading to a literature of apocalypse that employs a broad range of scenarios. In the end, our interest in these kinds of stories comes down to a fundamental human impulse--to explore our worst fears in order to make them more tolerable. When you read such a novel, you, as the reader, are cast in the role of a survivor, just by reading. And when you finish the book and look up, the world is still there. In past interviews you've mentioned that one of your goals was to write a "work without magic." Though all of the fantastical elements originate from science gone wrong, one could argue that characters like Amy, Alicia and Zero end up generating a mythical quality, and that a sense of magic accrues to them despite their worldly origins. Did you set out to build a new mythology or was this just an aspect of the novels that grew in the telling?

In past interviews you've mentioned that one of your goals was to write a "work without magic." Though all of the fantastical elements originate from science gone wrong, one could argue that characters like Amy, Alicia and Zero end up generating a mythical quality, and that a sense of magic accrues to them despite their worldly origins. Did you set out to build a new mythology or was this just an aspect of the novels that grew in the telling?

One of my intentions for the trilogy was that it would tell a very human story that, many years down the road--a millennium, in fact--would become the basis for something rather like a religion. The trilogy begins this way (Jonas Lear goes looking for the virus that is the basis of the vampire legend), and ends this way, in the figure of Amy, who has become a central figure in the mythology of a future civilization. This pet interest of mine came about as a consequence of a course I took in college in Medieval European history. As a requirement for the course, I had to pick a book off a list and give a presentation to the class. The book I chose was more archeology than history, tracing the origins of the King Arthur tale. As it turns out, the "real" King Arthur was a Celtic chieftain, a kind of local warlord, who probably ate with his hands, wore animal skins and lived on a dirt hill--hardly the shining lord of Camelot. But he did succeed in marshalling some of his fellow warlords to forestall a complete Anglo-Saxon takeover in his region of the British Isles, and over the years, this story morphed into something that now sits at the heart of the British cultural pedigree. I was completely taken by this notion that every legend has an origin, and that this origin is probably very, very human.

With The City of Mirrors, you were able to revisit events of the first novel through other eyes. Was this your original plan, or were these scenes that you planned for the first novel and then moved?

I planned this from the start. Each of the novels goes back to the beginning, to show you something from the early days of the apocalypse that you didn't get to see the first time around, or only glimpsed from the corner of your eye. I enjoyed doing this for its own sake, but it was also part of my working thesis--that the past is always present.

Did anything play out differently in The City of Mirrors than how you originally conceived it? Were there any characters that took over and moved the work in a different direction?

The biggest shift was that I had to push the story forward more years than I had planned. This occurred for technical reasons (one of my characters needed 20 years to accomplish a particular task, more time than I'd originally intended), but it played into my hands, because the characters' ages caught up to my own. Peter, Alicia, Sara, Michael et al. are now in their 50s and in a position to run things. They're also wrestling with the issues of midlife--being empty nesters, looking beyond the roles they've occupied and wondering what comes next. It worked very well for the story and allowed me to tap into many of the concerns of my own life.

Much has been written about your move from being a writer of "literary" fiction to a writer of "genre." Do you feel these labels do a disservice to the reader and the writer?

I think they can be useful in terms of directing readers to works they might enjoy. But these are broad categories with a great deal of overlap. What does it mean for a work to be "literary?" I wrote two novels that were described and marketed that way, but when I sat down to write The Passage, I didn't really go about things differently. I write how I write, and the human questions that concern me as a writer and a person don't really change. The only real difference was that I had to manage more characters, and all of these characters were constantly running for their lives--a very crystallizing thing for characters to do. As for genre: I'd argue every book belongs to one genre or another, which is to say it shows some obedience to the kind of story that it is and acknowledges other, similar stories. Moby Dick is an adventure novel. The Odyssey, though a poem, could be described as the greatest road-novel ever sung. And there's nothing that prevents a novel that overtly embraces a popular genre from also being a work of true greatness. The example I always return to is Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove. It's an absolutely by-the-numbers western, ticking off every trope on the list. But it's also a masterpiece of literature. --Donald Powell, freelance writer