|

|

| photo: Michel Arsenault | |

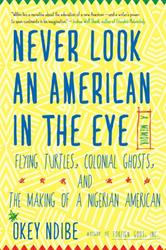

Okey Ndibe's memoir, Never Look an American in the Eye: A Memoir of Flying Turtles, Colonial Ghosts, and the Making of a Nigerian American (Soho Press, $25), explores the experience of the traveler and immigrant, trying to make sense of all the possibilities and challenges of American culture. Ndibe first came to the U.S. to serve as founding editor of African Commentary, a magazine published by Chinua Achebe. He has taught at Brown University, Connecticut College, Simon’s Rock College, Trinity College and the University of Lagos (as a Fulbright scholar). He is the author of two novels, Arrows of Rain and Foreign Gods, Inc., and his award-winning journalism has appeared in the New York Times, the Guardian and the Hartford Courant. Ndibe and his family live in West Hartford, Conn.

Given the polarization of national opinion regarding immigration, I have to ask about the title of your book. Did the title come about during the past few months?

The title emerged through an interesting evolutionary process--and then proved rather fortuitous. Throughout the writing of the memoir, my title was Going Dutch and Other Misadventures. But soon after I finished writing, I traveled to Italy and South Africa to take part in literary festivals. In discussions with other writers and readers in those countries, I was rather surprised that few people were familiar with the cultural and social connotation of the phrase "going Dutch." Since I didn't wish to confound my non-American readers, I changed the working title to Robbing a Bank and other Misadventures. It took a perceptive second reader--I believe a member of the marketing team at Random House--to suggest Never Look an American in the Eye. And, of course, once I heard it, I recognized its sheer brilliance. I realized that the title was organic and evocative. It both captures something essential about my book and taps powerfully into the current of one of the great contemporary debates in the U.S. A part of me felt jealous that I had not been first to see that this was the title.

You were born in 1960, and came to the U.S. in 1988 by a combination of writing skill and lucky coincidences involving the writer Chinua Achebe. The section of your book that relates this part of your story also mentions how, as a younger man, you were quite an enthusiast for American wrestling. I couldn't help but think there was a similarity there--how wrestling is executed so exceptionally that the viewer is left wondering which parts are skillfully choreographed and which are random.

I never quite thought about it that way, but your insight strikes the bull's-eye! Come to think of it, that whole experience is part of the ineffable economy of anybody's life, viewed retrospectively. When one looks back on one's life, one often sees certain patterns--the ways in which a number of coincidences, happenstances and seeming accidents intersected with and leavened one's dreams and plans to produce the sum of one's experiences. There emerges a pattern that is at once breathtakingly logical and deeply mysterious. There's a loneliness that you write about, from your early days in America, that seemed like more a product of your cultural background than literally "being alone"--you had to interact with a lot of people, getting the African Commentary magazine started. Do you look back on those feelings differently now?

There's a loneliness that you write about, from your early days in America, that seemed like more a product of your cultural background than literally "being alone"--you had to interact with a lot of people, getting the African Commentary magazine started. Do you look back on those feelings differently now?

Yes, I did interact with a lot of people, but there was nevertheless that sense of being cast adrift, that feeling of a dislocation. I'd suggest that this sensation is a fundamental one, integral (to one degree or another) to the experience of anyone who has ever moved to a different place and different cultural zone, period. There's a shock to the psyche--on several fronts. For example, I had read about winter in books, but how could I--a tropical being all my life--possibly understand even the barest ramification of the word? Remember: I had lived for close to 30 years in a tropical country where, almost year-round, the temperature is 80 degrees and higher. I felt devastated to come from all that heat into a zone that felt absolutely arctic. Another example: in Nigeria, I was used to friends gathering every evening in my apartment--to drink, eat, share stories about our romantic disasters or fortunes, laugh about the absurdities in which our lives were mired, inveigh against corrupt military rulers and so on. Each evening, if I happened to be in town, friends and neighbors would just stop by, no prior arrangement, no invitation needed from me. And when we carried on 'til quite late, some of my visitors would just stake out positions in the two bedrooms or on the couch and doze off for the night. And did I treasure those recurrent, rowdy get-togethers! But in America, people seemed to have other priorities. That, or they were too busy for that kind of daily, unplanned, informal roasts. I found that Americans often required a clearer agenda, some more definite purpose, for social gatherings. And I discovered that that most Americans didn't expect you to just drop by at their homes--invoking the name of friendship. You had to wait to be invited. I've had all these years to adjust to the "American" way. Even though I have lived in America for as many years as I lived in Nigeria, the adjustment--I must confess--is still ongoing. Except that, whenever I return to Nigeria, I also see myself adjusting to certain Nigeria idiosyncrasies--for America has also changed me, profoundly in some respects. --Matthew Tiffany, LCPC, writer for Condalmo and psychotherapist