|

|

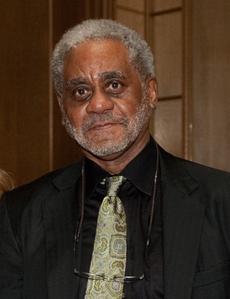

| photo: Lynette Huffman-Johnson | |

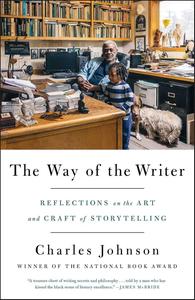

Charles Johnson is an artist, MacArthur fellow and professor emeritus at the University of Washington in Seattle. A student of the late John Gardner, he has gone on to teach many other writers and has been hailed by James McBride as "one of America's greatest literary treasures." Johnson's body of work encompasses fiction, nonfiction, philosophy, cartooning and screenwriting. In 1990, he won the National Book Award for his novel Middle Passage, which has been adapted into a play, and in 2002 he received the Arts and Letters Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In his new book, The Way of the Writer: Reflections on the Art and Craft of Storytelling (Scribner), Johnson offers 40 years of lessons on writing, reading, publishing, critical theory and the creative process. Our review is below.

Why write a book about writing?

Around 2010, the poet Ethelbert Miller asked if he could interview me for a year. He asked me 400 questions on every subject you could imagine. He would put a title on my answers, which became kind of like essays. He put artwork with it, too. And after it was done, my agent placed all of it with Dzanc Books, which last year published a 672-page book called the Words and Wisdom of Charles Johnson, which is about everything--Buddhism, fatherhood, the visual arts, you name it.

Some people who read that suggested that there was a separate book that could be conjured from this 672-page book, just on the craft of writing. So I said okay--let me go back over it and expand on and polish my answers, and I added three essays to the book.

Forty years ago, when I first started teaching at age 28, the last thing on my mind was doing a book on the craft of writing. But it's something I know; I spent half my life teaching this. So there's lots I have to say about the subject. And because I'm retired--I'm professor emeritus now--I thought maybe it's the right time to do this.

Why tell students not to limit themselves to one art form?

Because that's how I live. I do many things, and they all reinforce each other. I see myself as being an artist. Sometimes the art I do is literary. Sometimes the art I do is visual. Sometimes the art I do is martial art. It all depends on what I want to do during a given day. And I don't call myself "a writer." I always cringe in a certain way when somebody calls me that. I say, I tell stories: I'm a storyteller. A storyteller and an artist who works in different mediums.

I see my body of work being like a house, or a mansion with many rooms. And there are different kinds of art in all of those rooms. But they all talk to each other. If I haven't written about a subject, it's quite possible that I've drawn something about it, and published that: as an illustration or as a cartoon, an editorial cartoon, as something. All of it connects.

That kind of free-ranging curiosity may be viewed with skepticism, if not outright hostility, by some.

It is a natural and unfortunate human tendency we have to oversimplify things for the sake of making them manageable. We'll say for example, my friend August Wilson, you know, "he's a playwright." And that's true; he wrote 10 plays. But he was a poet, too. And the poetry part of his life is manifest very clearly in the dialogue in his plays. We manage people by putting them in little convenient boxes, constructed by people who can't see beyond the fact that all the arts are interrelated and they are interrelated with the sciences as well.

And now I'm really going to lay one on you: we do that all the time with artists of color. We pigeonhole them constantly. If they're Native American, we want them to write about the Native American experience. They may have a degree in nanotechnology. If they're black Americans, we want them to write about the black experience.

One of the great fights in life--and this is a quote from one of my other interviews--is not to allow anything or anyone to limit you. I truly believe that. No one can really understand and guide your talents but you. No one can understand its depth and breadth but you. You do what brings you joy in terms of the creative process. It doesn't matter what medium we're talking about. This is a gift you have. And I think it's a god-given gift, to be honest about it.  There's a lot of Buddhism in this book.

There's a lot of Buddhism in this book.

For an artist, the vision of the Buddhadharma is extremely... helpful. The Buddhist experience is the human experience. It allows us to clear away a lot of cultural and social conditioning. Bhikkhu Bodhi, a Buddhist teacher, talks about it as being like a conceptual painter who has painted over an object. And we have to get rid of that conceptual paint so we can have a fresh experience with whatever phenomenon we're talking about. And that's called beginner's mind. For an artist that's invaluable. One of the things you want as an artist is to experience and give to others a new fresh vision of something.

What books do you recommend to readers of Shelf Awareness that might've escaped their notice?

Chicago Heat by Clarence Major. The Collected Poems of E. Ethelbert Miller. The Writer's Brush: Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture by Writers, edited by Donald Friedman, is a wonderful, wonderful book and it would be wonderful in our educational institutions, K-12, because it would show young people that you don't have to limit yourself if you have a broad talent.

There's a whole list in chapter seven of works I expected my students to know. But by the early '80s, they didn't know them [laughs]. Albert Murray's The Hero and the Blues, if we're talking about a writer of color. Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man.

Any advice to aspiring artists (that isn't in your book)?

For a young writer, getting published should not be the main thing, if you're really serious about your overall body of work. I quote a New York editor [who] said you shouldn't publish your first novel. And secondly, not everybody can be published. And thirdly, you shouldn't see yourself as a failure if you don't get published.

But even more importantly, you should see every book that you do as part of a larger body of work. And how one book advances beyond [or] complements another. And the only way [younger writers] are going to do that is if they ask themselves some serious questions about what it is they're bringing to the table as a writer. What is it they're bringing to literary culture that is not there now? What void are they filling in terms of our literary culture?

There are writers who knew exactly what they were bringing to the table. Zora Neale Hurston knew, in terms of her work in black folklore. Saul Bellow knew, in terms of being a Jewish writer who was finding the universal in the specific Jewish experience. Same thing with Ralph Ellison looking at the black experience.

A lot of young writers want to be a writer before they have a great story to tell. But, okay, what story do you have to tell that is going to be worthy of all the time and energy that you're going to have to put into it, and worthy of a reader's time? Because readers are hard-pressed for time. --Zak Nelson, writer and bookseller