|

|

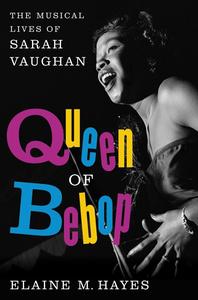

| photo: Nick Kramer | |

Elaine M. Hayes, jazz historian, writer and editor, is recognized within the music history community as the expert on Sarah Vaughan. She earned her doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania, and lives in Seattle with her husband and son.

Hayes's meticulously researched biography, Queen of Bebop: The Musical Lives of Sarah Vaughan (Ecco, $27.99), focuses on the voice of one of the most amazing vocalists of the 20th century. Hayes weaves in the story of Vaughan's life, along with racial, social, and gender history and issues.

You've said that Sarah Vaughan was your crossover moment.

I was trained as a classical musician and didn't discover Sarah until college. I immediately fell in love with her voice--the way she used her vibrato, the way she'd swoop from the bottom of a range up to the top; it was very exciting. In graduate school, when I took a seminar on women and jazz, I decided to write a paper on her and it grew from there.

There are many ways race impacted Sarah's life and career. Most of them need no explanation--after all, she toured in the South in the '40s, '50s and '60s. But one aspect is not so obvious: the way white critics discussed vocalists. Vaughan's tone was "full and rich like velvet or oozing honey, yet agile and supple, almost light as air." Yet, white female voices were considered beautiful, feminine, while black voices were not.

Since the music was heard on the radio, listeners had to be told what kind of person was singing. White critics were invested in reinforcing racial barriers, so they employed code words to maintain those boundaries, like "earthy," and used a very limited vocabulary for black voices. Black critics, black writers didn't have the same agenda. To them, black singers like Bessie Smith, Dinah Washington and other traditional blues shouters had very beautiful voices.

It was a way to keep white listeners from getting too emotionally invested in black performers. The one thing I love about Sarah is that her music is very emotionally intimate--she's talking about my life. Creating that kind of human connection between white listeners and a black person was frowned upon. So the way that the voices were talked about perpetuated beliefs.

Vaughan was typecast as a blues or jazz singer, while white vocalists had "the freedom of flexibility and the privilege of choice." However, Dave Garroway, in his radio broadcasts in the late '40s, did not "reduce Vaughan to her body." Can you describe what that meant?

When I listened to Garroway's radio broadcasts, he would talk about her voice using a lot of the vocabulary that had been used to describe white vocalists. This is not to say in any way that Vaughan was not an African-American vocalist, but he seemed less interested in maintaining the barriers we were talking about. He would tell people to close their eyes and relax their minds and just enjoy the sound. His approach to Vaughan blurred racial boundaries. There is so much in your book about racial, social, gender issues as seen through the prism of Sarah Vaughan, but... her voice! "Vaughan... together with her fellow musicians, created a seamless progression of tone colors and timbres as each pairing came in and out of focus. Together, they crafted a distinct sonic world."

There is so much in your book about racial, social, gender issues as seen through the prism of Sarah Vaughan, but... her voice! "Vaughan... together with her fellow musicians, created a seamless progression of tone colors and timbres as each pairing came in and out of focus. Together, they crafted a distinct sonic world."

When I would interview the musicians she worked with, they would describe her as an instrumentalist. In the context of how jazz singers worked, that's the highest praise they could give. Actively responding to the musicians... that was just one of the things that made her artistry exceptional.

Her singing changed the outlooks of musicians and critics. She left them, especially vocalists, "gasping in amazement at her daring innovations and vocal dexterity."

What she did with her voice was technically very difficult, and her harmonic choices--she'd choose these notes that weren't obvious in the harmonic framework. A really great album that shows this is Sarah Vaughan Live at Town Hall (1947) with Lester Young. One of the things that makes this so great is you can hear how the audience responded to her singing. Listen to "I Cover the Waterfront," or "I Cried for You."

"Mean to Me" from the album is not available, but her recording from 1945, backed by Dizzy Gillespie's Septet (with Charlie Parker on alto sax and Max Roach on drums) is. I wish we had a live performance of this band!

When we listen to "Ave Maria" (1951), we can hear how Vaughan, with her four-octave contralto, could easily have become an opera singer.

It's my sense that that was one of her dreams. Marian Anderson was one of her idols. She had the voice, but she was black and came from a working-class home, and classical music required access to certain kinds of teachers, conservatories, learning foreign languages--there was a financial and class barrier.

In the '50s, some of her greatest supporters/critics accused her of selling out, of being too commercial. "Critics believed that musicians, especially black musicians, had a moral obligation to perform (and record) jazz, and that they should remain untarnished by crass commercialism." But as Nat King Cole said, why starve?

Billy Eckstine, another black crooner, said, "Would you feel better if I died from a drug overdose and couldn't feed my family?" The critics created an idea of how black artistry should work.

Nat King Cole, Billy Eckstine, Sarah Vaughan, Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie--all jazz musicians who definitely had jazz cred--they wanted to be successful as possible, and they understood that was related to financial and commercial success.

That would also give them power, more control over their art.

Exactly. Sarah became a pretty popular singer in the '50s, and as she made the transition from jazz and bepop to pop, critics got really angry with her. But she wanted the freedom to sing what she wanted. In the '50s, she was fine-tuning her style, so she could kind of sneak in a lot of jazz elements into pop songs. She became quite good at singing for a pop audience while remaining interesting to a jazz fan.

Then she widened her audience and moved into what you call her third stage, when she emerged as a "symphonic diva."

In the 1960s, jazz (and pop) had a really hard time as rock became huge, so musicians had to figure out how to make a living. Sarah had a number of very difficult years, but in the process, she found a new opportunity--she started singing with symphony orchestras. It allowed her to first of all find beautiful venues where she was treated with respect and appreciated, but also allowed her to explore her operatic side.

Vaughan insisted on being considered a "singer," rather than being pigeonholed. When she made music, she "became a human being instead of an African-American. It released her from social and cultural limitations." But she wasn't free from the limitations of being a woman at her particular time in the world. She was only free on the stage.

I think so. Near the end of her life, she wrote an op-ed for USA Today. She talked about the special meaning music had for her. Going into the recording studio, differences in age, in musical style, in race, gender--they all disappeared in the moment of making music. Singing, communicating who she was through her voice, expressing herself... but once she stepped off the stage, there was still the real world. --Marilyn Dahl