|

|

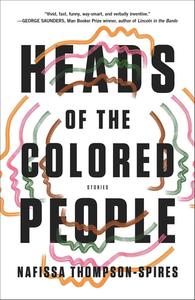

| photo: Adrianne Mathiowetz Photography | |

Nafissa Thompson-Spires's work has appeared or is forthcoming in the Paris Review Daily, Dissent, Buzzfeed Books, the White Review, the Los Angeles Review of Books, StoryQuarterly, Lunch Ticket and East Bay Review. She is a visiting assistant professor of Creative Writing at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Heads of the Colored People (reviewed below), a collection of stories, is her first book.

In your author's note, you give credit to 19th-century writers who narrated black life in particular ways. Why was it important for you to continue and to expand on this tradition?

I like this question a lot. Even though my goal in the collection is to think through a particular experience of blackness in this contemporary moment (during my lifetime, really), there's an imperative for black art to look back--both out of homage and respect, and because while many things have changed for the better, a lot of issues are nearly the same, or repeated. Those 19th-century writers were trying to think about what it would look like for black people to have full rights of citizenship. We're still doing that with Black Lives Matter, protests against state-sanctioned violence, voter suppression, etc. These aren't new; they're extensions and rearticulations of ongoing battles. A lot of black writers have theorized a kind of cyclical sense of time for black people, and when you read work from the 19th century, those cycles become apparent.

From a craft perspective, I'm a big fan of intertextuality and the richness older texts can lend to newer ones. So, I'm referencing and in conversation with James McCune Smith, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and all these black writers, but also some white ones like Charles Brockden Brown. I love what we can signal through unexpected juxtapositions.

This brings me to your nod to Shirley Jackson in "Belle Lettres." Like Jackson, you filter shocking behavior through the mundane--to unsettling (if humorous) effect.

I've been influenced by writers like Jackson and Flannery O'Connor and Ishmael Reed who disarm with dark humor. It's not so much an intentional craft choice as it is my mode of getting through life. I'm a highly sensitive person, and the distance humor creates is often the only way I can tolerate upsetting content. I especially enjoy a deadpan delivery. My mom used to say I reminded her of Ben Stein and Janeane Garofalo. I was also a failed class clown who wanted to become a standup comedian. Perhaps that desire still exists and comes out in my work.

Quite a few of your characters struggle with their mental health.

It was important to address those concerns from a variety of angles, both with humor and seriously. Many people make blanket statements claiming black people delay addressing mental and physical health concerns or don't go to therapy, but that isn't true in my own life. Nearly all my black friends and family members (except a few very resistant ones) have been to, or are currently in therapy, and so am I. Mental health struggles are just another part of creating realism. Most of the characters are one of only a few black people in their respective environments, if not the only black person. Why was this an important element to include?

Most of the characters are one of only a few black people in their respective environments, if not the only black person. Why was this an important element to include?

I think that theme of isolation is perhaps more autobiographical than a lot of the other themes in the collection. I was often the only or one of a few black girls (or black people, or sometimes POC in general) in spaces. I attended a predominantly white private school from elementary through high school. In grad school it was more of the same. I've even taught courses in which I was the only black person in the room.

I'm not sure people who haven't experienced that can understand how jarring that is and the ways it teaches you to see yourself, to monitor your behaviors, to feel like an example all the time. I've also dealt with white people who became too comfortable in my presence and treated me like I wasn't black enough or made comments about my being "exceptional" because I didn't fit their stereotypes. I hear the same things from black friends with similar backgrounds. A lot of the stories in the collection are me shining a light on those situations and problematizing them.

You interact with the body in a variety of ways, addressing issues such as colorism, eating disorders, mortality and fetishization.

One of my interests is in the vulnerability of the black body, both historically and now. So the collection deals with a range of bodily harm--from police brutality in two stories to eating disorders and chronic illness in others. I'm interested in the idea that upper middle or middle class positions don't protect black bodies, that blackness supersedes class.

With eating disorders, traditional narratives frame it as a white illness; there's this pervasive idea that black women are more body positive. That may sometimes be true, but I also feel the more black people live under the pressure and pathology of white aesthetics, the more likely they are to internalize that. I grew up not wanting to be "thick," but as emaciated as possible. I used to pray that my butt would never be big and that I would get skinnier. That's appallingly sad to me now, as an adult, but I can't say I'm any less fat-phobic now. Even after years of therapy and recovery from an eating disorder, I worry about my weight all the time. Some of that's the nature of growing up in Southern California--a very fat-phobic place--some of it is familial, some of it is just my own particular issue, but a lot of it is because I subscribed to white body ideals.

Vulnerability coexists with acts of resistance (to both external and internal forces) in your stories. How do you see these elements working, both separately and in tandem, in your writing?

Black characters are often presented as either exceedingly vulnerable--to oppression of all kinds, which makes sense--or exceedingly strong. bell hooks has written at length about the myth of the strong black woman and how that idea of inherent resilience or superhuman strength can create a lack of empathy for black women's pain. I didn't want to slip into the binary of pure victimhood or super strength, so a lot of the characters are actively resistant. But I hope they're round, too, that their vulnerabilities are visible and ongoing and that their (small) triumphs are, too. This is why many of the stories end in medias res instead of with resolute endings. --Shannon Hanks-Mackey, freelance editor and managing editor at the Black Scholar