Although both The Glass Castle and Half Broke Horses are your own family stories, you experienced the former directly and reconstructed--or reimagined--the latter. What, for you, defines the difference between writing from memory and writing about personal history?

In writing The Glass Castle, the challenge was to be honest with myself. With Half Broke Horses, it was to be as true as possible to the story and the voice of my grandmother.

As a follow-up, what were the

challenges--and, conversely, the rewards--of writing the fictionalized account

of Half Broke Horses after the

memoir?

As a follow-up, what were the

challenges--and, conversely, the rewards--of writing the fictionalized account

of Half Broke Horses after the

memoir?

They were shockingly similar. It's all about story telling. It's all about trying to ferret out the truth, to explain how we got where we are, and how the answer is always there--if you're willing to dig deep enough.

For generations, the women in your family (including yourself) have coped with tremendous hardship, both physical and emotional, and yet have found creative and sustaining ways to survive. To what do you attribute the strength it has taken to face these challenges?

Necessity

is the mother of invention. That was always one of my mother's favorite

sayings, and she learned it from her mother, Lily. Lily was not only a school

teacher, but she also brought in extra money driving the school bus--which wasn't

really a bus, but a hearse with the words "SCHOOL BUS" painted on the

side. When the hearse got stuck in the mud or in a ditch, which it did a lot,

Lily would make the students get out and push--and recite Hail Marys while they

pushed. She'd holler at them, "Push and pray, kids, push and pray!" I

think that's not a bad philosophy for life. I believe in a higher authority, I

believe in the power of prayer and positive thinking and all that good stuff,

but I'm also a big fan of the power of pushing, of rolling up your sleeves and

doing the hard work that needs to be done. The combined power of pushing and

praying makes us all pretty strong.

Necessity

is the mother of invention. That was always one of my mother's favorite

sayings, and she learned it from her mother, Lily. Lily was not only a school

teacher, but she also brought in extra money driving the school bus--which wasn't

really a bus, but a hearse with the words "SCHOOL BUS" painted on the

side. When the hearse got stuck in the mud or in a ditch, which it did a lot,

Lily would make the students get out and push--and recite Hail Marys while they

pushed. She'd holler at them, "Push and pray, kids, push and pray!" I

think that's not a bad philosophy for life. I believe in a higher authority, I

believe in the power of prayer and positive thinking and all that good stuff,

but I'm also a big fan of the power of pushing, of rolling up your sleeves and

doing the hard work that needs to be done. The combined power of pushing and

praying makes us all pretty strong.

How did the success of The Glass Castle inform the writing of Half Broke Horses?

I've come to really trust readers. They were incredibly smart about The Glass Castle and understood the story so much better than I could have ever hoped. So when readers started suggesting that my next book should be about Mom, I listened--even though it ended up being about Mom's mom, it does tell her story by explaining her childhood.

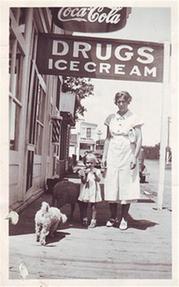

Your grandmother, Lily Casey Smith,

emerges from Half Broke Horses as an

indelible, complex character--a woman in many ways ahead of her time to whom

today's readers can immediately relate. What did you learn about yourself in

the course of writing her story?

Your grandmother, Lily Casey Smith,

emerges from Half Broke Horses as an

indelible, complex character--a woman in many ways ahead of her time to whom

today's readers can immediately relate. What did you learn about yourself in

the course of writing her story?

Lily was one tough broad and I say that with both disdain and admiration--because I'm alarmingly like her. I recognized myself in so many of her thoughts and actions, including some not always endearing traits. I also learned a lot about Mom, about her quirks and her values and why she made some of the choices that she did.

What, for you, is the most important thing we can all learn from Lily Casey Smith?

My ambition

for Half Broke Horses is that people

who read it will be moved to think about their own parents or grandparents or

great-grandparents. While touring on behalf of The Glass Castle, so many people have said to me that they're not

as strong as I am--that they never could have survived without indoor plumbing

or electricity--and while I'm flattered by their comments, they're nonsense.

Of course they could have. A hundred years ago, pretty much no one had these

luxuries. So I'm hoping that people who read Lily Casey Smith's story will

think about their own ancestors--most of whom were pretty tough characters who

survived without the things that we've come to view as necessities and who did

the back-breaking work that many of them needed to do to survive. I hope that

the readers are reminded that they have the same blood running through their

veins.

My ambition

for Half Broke Horses is that people

who read it will be moved to think about their own parents or grandparents or

great-grandparents. While touring on behalf of The Glass Castle, so many people have said to me that they're not

as strong as I am--that they never could have survived without indoor plumbing

or electricity--and while I'm flattered by their comments, they're nonsense.

Of course they could have. A hundred years ago, pretty much no one had these

luxuries. So I'm hoping that people who read Lily Casey Smith's story will

think about their own ancestors--most of whom were pretty tough characters who

survived without the things that we've come to view as necessities and who did

the back-breaking work that many of them needed to do to survive. I hope that

the readers are reminded that they have the same blood running through their

veins.