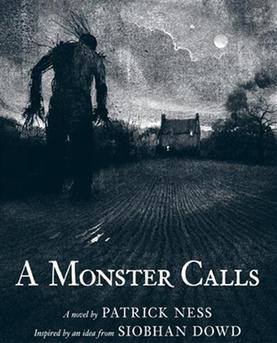

A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness, inspired by an idea from Siobhan Dowd, illus. by Jim Kay (Candlewick, $16.99, hardcover, 9780763655594, 224p., ages 12-up, September 27, 2011)

Wasting not a word in a narrative leavened with humor, Patrick Ness describes the isolation that accompanies the feelings of grief, pain and anger in a child whose mother is battling a terminal illness.

Wasting not a word in a narrative leavened with humor, Patrick Ness describes the isolation that accompanies the feelings of grief, pain and anger in a child whose mother is battling a terminal illness.

What do you do when you are losing the person who means the most to you? And what if you had no one to talk to about it? If you are 13-year-old Conor O'Malley, you summon a monster. Though Conor doesn't believe that he called the monster, it nonetheless appears outside his bedroom window just after midnight. Conor is not afraid. "I've seen worse," he tells the monster. Much of the novel's humor emanates from Conor's delightfully sassy demeanor, most often triggered by the monster. Even though the monster stands more than 30 feet tall with a torso made of the trunk of a yew tree and spikey leaves that add to its prickly bearing, and--in artist Jim Kay's rendering of the giant--presses against the boy's house as if to topple it, Conor is not afraid. He has seen worse. His mother is going through yet another round of treatment, and "her bare scalp looked too soft, too fragile in the morning light, like a baby's." Every day when Conor goes to sleep, the same nightmare haunts him--the one "he would never tell another living soul about." At the same time that the dream starts its nightly visits, his classmate Harry begins bullying Conor at school. This, too, Conor keeps secret. His mother has enough to think about; his father lives half a world away with his new wife and baby in America. Lily Andrews had been "like a sister who lived in another house"--until she told some people about Conor's mother (which "changed the whole world in a single day"), and he definitely would not tell his grandmother.

Conor's relationship to the monster changes over the course of their visits. The monster--which transforms itself from the very yew tree that stands guard at the nearby graveyard--comes back the next night, again at 12:07. He promises Conor that he will tell three stories, and then Conor must tell the fourth. Conor has no time for stories. He wants his mother to be well, and he does not want to stay with his grandmother while his mother is in the hospital. He wants a happy ending. "I do not often come walking, boy, only for matters of life and death," the monster says. "I expect to be listened to." So Conor listens, and, through the monster and his three tales, he begins to make peace with the chaos of his life. Not because the stories go the way stories often go. The monster's stories always have a twist: the prince is not all good and the witch is not all bad; the apothecary possesses more faith than the parson. Instead, the peace grows from the monster's testimony that creation and destruction are part of a continuum, and in everything there is light and dark, side by side. "I am the wolf that kills the stag, the hawk that kills the mouse, the spider that kills the fly! I am the stag, the mouse and the fly that are eaten!" the monster explains. After the second story, as Conor joins the monster in his destruction of the parsonage, they also wreck a settee "not unlike Conor's grandma's." Conor realizes, when the monster leaves, that they have destroyed his grandmother's sitting room.  And, in the course of the third story, about an invisible man, the monster defeats Harry in the cafeteria. But the headmistress summons Conor (not the monster) to her office. Is the monster real or is he part of Conor? The brilliant illustration of Conor upending the lunchroom chairs depict him in the same position as the monster on his first visit to Conor's window, arms pressed forward and an energy coursing from his fingertips. What matters is that when Conor needs the monster most, he is there: Conor confides his nightmare to the monster, the fourth story. "I do not often come walking, boy, only for matters of life and death."

And, in the course of the third story, about an invisible man, the monster defeats Harry in the cafeteria. But the headmistress summons Conor (not the monster) to her office. Is the monster real or is he part of Conor? The brilliant illustration of Conor upending the lunchroom chairs depict him in the same position as the monster on his first visit to Conor's window, arms pressed forward and an energy coursing from his fingertips. What matters is that when Conor needs the monster most, he is there: Conor confides his nightmare to the monster, the fourth story. "I do not often come walking, boy, only for matters of life and death."

This is not an easy book. Conor's honesty is raw. Patrick Ness tells the truth about grief--that it is wrapped up with anger and sadness and fear. Grief is a messy business, and it must see the light of day. Those who do not bring it forth risk retreating into silence and isolation, as Conor does before the monster calls. In his Chaos Walking trilogy, Ness created an alien world in which everyone's thoughts are audible as "Noise." Here Conor walks in a world we recognize, yet buries his secret in silence. Until the monster comes: "You know that your truth, the one that you hide, Conor O'Malley, is the thing you are most afraid of," he says. Ness creates a paradoxical "monster" with the power to mete out justice and the healing properties of a yew tree; he's an archetype as ancient as the Green Man, who witnesses Nature's cycle of creation and destruction over centuries. He knows that Conor can free himself by telling his truth, and that whatever may happen, Conor will survive. The monster stays with Conor until he understands that the monster truly sees him and knows him--and accepts him exactly as he is, with all of his complexities. There is no one way to grieve, and no wrong way to grieve. That is the gift Patrick Ness and his monster give to every reader who fears the loss of the one they love.

A MONSTER CALLS. Text copyright © 2011 by Patrick Ness. Inspired by an idea from Siobhan Dowd. Illustrations copyright ©2011 by Jim Kay. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, Mass., on behalf of Walker Books, London.