If this sounds a lot like Cormac McCarthy's The Road, it is... but where McCarthy envisions a post-apocalyptic parched landscape with illusory salvation at the end of a journey to the sea, Smith's realistic landscape is full of water and wind where escape means traveling away from the sea. His survivors scrounge below The Line, a national emergency boundary 90 miles inland from the Gulf. A small band of them are reluctantly led by Cohen, a carpenter haunted by the death of his wife and unborn daughter in an earlier storm evacuation. Circumstances throw him in with a teenaged New Orleans Creole girl, a young father and his son, and various women escaped from a snake-handling zealot determined to repopulate the world with his offspring. With guns, a broke-down Jeep and a stash of $100 bills recovered from a buried casino vault, Cohen takes his rag-tag group through a gauntlet of relentless rain, washed-out highways and even-better-armed bandits.

The satisfaction of Rivers comes from Smith's finesse in creating a realistic thriller within the fiction genre of cataclysm. His scenes are as real as 24-hour Weather Channel videos. Cohen is a complex character who takes charge when he needs to while never forgetting his personal losses. He sees things as they are: "There was betrayal and hope and fear and love and hurt and yesterday and today and tomorrow twisting around in his head like a bed of snakes striking against one another for supremacy." Smith's creation of The Line is an inspired metaphor for a world divided between the haves and have nots. Above The Line is some semblance of law and order, our good old world of fast food and normal life. Below The Line, you're on your own. As Aggie, the snake-handling zealot says in a moment of clarity: "The Line is a problem for all of us.... It's the symbol of hate.... The Line don't do nothing but point fingers.... It tells us some people are alright. Some people ain't." A fitting symbol of Smith's cataclysmic future is a hunched-over old man wearing a sign that says THE END IS NEAR--"but NEAR had been crossed out, and written underneath was HERE and all the words were streaked." Storm-battered as Rivers is, its words are never streaked, but instead, clear as a ray of sunshine. --Bruce Jacobs

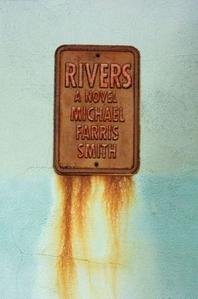

Shelf Talker: A debut novel about a Gulf Coast carpenter bearing his own burdens as he helps others bear theirs after a devastating climactic change.