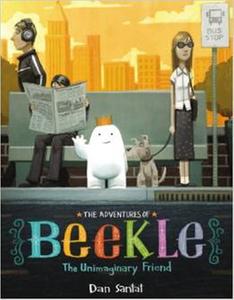

Earlier this week, at the American Library Association Midwinter Conference in Chicago, writer and illustrator Dan Santat won the 2015 Caldecott Medal for The Adventures of Beekle: The Unimaginary Friend (Little, Brown), the story of a snowman-looking fellow with limbs and a gold crown who eagerly waits "to be imagined by a real child." Santat spoke with Shelf Awareness about the book's very true origins as a metaphor for the yearnings of an expectant father.

|

|

Congratulations! How do you feel?

Thank you very much! I'm like pumping on adrenaline.

So tell us, what were the seeds of The Adventures of Beekle? We loved your completely original idea of an imaginary friend searching for his child.

The idea was inspired by the birth of my son--a metaphor for the birth of my son. When my wife told me she was pregnant, my first thoughts as a father were wondering what he would be like, his interests, his personality, how much of me would be reflected in him. There's an anxiety of expectations, and an unconditional love you know you'll have when you meet.

That's intertwined with my son's feelings on the first day of school, and finding friends that have the same interests that he had. That was a big part of the inspiration of the story, combined with doing a story from an imaginary friend's perspective. You typically think of kids designing an imaginary friend in their minds, but there's no input from the imaginary friend himself. He's programmed to say, "My purpose is to be your friend and that's all I'm meant to do."

But Beekle is overly concerned with, "I'm such a bizarre-looking imaginary friend, I wonder if anyone would want me?" and the idea that you were both meant to be together.

How did you come up with that setting--a kind of island of misfit toys with imaginary friends in limbo until they meet their child?

It's funny that you call it limbo, because for a while the island's name was Limbo. The imaginary friends serve a function, but they don't know what it is yet. If you look on the endpapers, there's a monster that plays the drums for a child who loves music [and other examples]; they're not aware of the other half that completes them. With Beekle, my struggle was to make him in such a way that he didn't give away his purpose. He's the only pure white character in the entire book; he represents a blank canvas.

Your Beekle-eye view of the subway is so spot on. Did you think of the sailing ship and the subway as a kind of journey to transition from his island of imaginary friends to the world of humans?

The spread that really communicates the journey well is when he's lost in a sea of commuters walking, and you don't see their faces, just a sea of legs. I was trying to portray a child's experience. It's not as intimidating to meet people eye to eye as it is when you see these giants. If you're little and you're sitting on a couch, your legs are dangling off the edge of the chair. That's evident in the scene in the subway. Every year I go to New York to meet with my publisher, and people on the subway have their faces in books or they're sleeping. They don't really make contact or look around or reach out to anyone. There's a sense of a loss of magic when you're an adult. Things don't seem spectacular because you've gotten a bit cynical with the world.

You see that in the cake and the strawberries, the music notes of the accordion; those are the bright colors. It was important to me to separate these two worlds--the childlike innocence from the reality of how the world is to an adult.

It's also wonderful that you characterize both Beekle and his child, Alice, as relatively friendless--or at least incomplete--before they meet. Do you see that as the role of the imaginary friend for children?

I honestly don't feel like children pick imaginary friends based on anything in particular. When I was a kid, I didn't have imaginary friends, but if I played make-believe, it was referenced by something I knew. I was going on an adventure with a Ghostbuster or Pac Man, things I experienced through culture. Talking with kids, not a lot of their imaginary friends reflected their interests or anything in particular about them.

For the message of making a friend, I found it to be important to find two halves to a whole. To have Alice find--not because she's an introvert or shy--to find a friend in a world created by her, fills that void. It's like having that "a-ha" moment when all the pieces are coming together. I didn't want the imaginary friend to sound clichéd, hairy monsters with horns and stripes that didn't reflect anything. I wanted them to reflect these children and their interests. You can tell a lot about these children without any dialogue in the book.

If you could say anything to young readers, what would it be?

Don't be afraid. Be fearless. Go out there and engage with the world. I think you will find it to be less frightening than you anticipated it would be. There's always someone out there for you. In the end, one person is all you really need. --Jennifer M. Brown