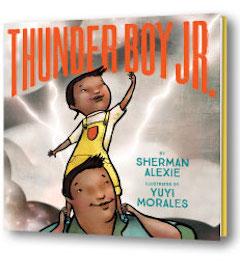

.jpg) Sherman Alexie is a poet, short story writer, novelist, filmmaker, performer and winner of the National Book Award for Young People's Literature for The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (Little, Brown). His debut picture book is Thunder Boy Jr. (Little, Brown, May 10, 2016), illustrated by Yuyi Morales. A Spokane/Coeur d'Alene Indian, Alexie grew up in Wellpinit, Wash., on the Spokane Indian Reservation and now lives in Seattle with his family. Here, he talks with Shelf Awareness about Mork & Mindy, scaring his sister, cultural chameleons and his path to writing young people's literature.

Sherman Alexie is a poet, short story writer, novelist, filmmaker, performer and winner of the National Book Award for Young People's Literature for The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (Little, Brown). His debut picture book is Thunder Boy Jr. (Little, Brown, May 10, 2016), illustrated by Yuyi Morales. A Spokane/Coeur d'Alene Indian, Alexie grew up in Wellpinit, Wash., on the Spokane Indian Reservation and now lives in Seattle with his family. Here, he talks with Shelf Awareness about Mork & Mindy, scaring his sister, cultural chameleons and his path to writing young people's literature.

I think it's safe to say at this point that you've chosen to be a storyteller in life. When you were growing up, were you surrounded by people who liked to tell stories?

I was surrounded by a couple types of storytellers. Those in the more traditional tribal mode, like my grandmother, who told a lot of old stories--not just ceremonial stories, but really reached back into the past for mythology and spirituality. And then I was also surrounded by, you know, alcoholic entertainers. My dad was hilarious and would go on and on about all the stuff that happened to him when he was a kid growing up, and as an adult. So I guess I was surrounded by sacred traditional storytellers and profane liars.

I was also coming of age with American stand-up comedy. The golden age was the mid-'70s through the mid-'80s. So, having the TV on meant you learned storytelling comic rhythm. So, all that was combined. I think I'm as much a product of Mork & Mindy as I was of powwow.

Did you always have a way with words?

Did you always have a way with words?

Uh, yeah... he says as he stutters. But I think it's part of tribal communication, certainly in the Native American world. They are incredibly quick-witted folks. My sisters who were not that academically gifted can just destroy me in arguments. They can just slap me up and down. I grew up in a highly verbal environment. Very funny, very caustic. So you had to become adept with language, spoken language, or just stay home.

Did you have people who encouraged you to write?

My big sister always thought I was going to be a writer. She read a few of my papers when I was in third or fourth grade and said, "Oh! You're going to be a writer." Once I wrote her a story about her trailer house being haunted. And it scared her so much that she never wanted me to write her another one.

Haunted by... ghosts?

By skeletons. Yeah. Trailer-house hallways are narrow, so when the skeletons are walking down towards her room they're brushing the walls and making a squeaking noise, and so I wrote on the page Skweee! Skwee! Skwee! For years afterwards I could scare her by making that noise: Skwee! Skwee! Skwee!

Do your own kids have a tie to their heritage?

Yeah, they have a tie to that, they have a tie to everything we are. What I'd like to hope is that I kept more good stuff than bad from my heritage. And I hope my kids do the same thing. I mean, they're standard Commie leftie Seattleites. You know how that is.

Do they seek out books by Native American authors?

They read what they want. They pick out their own books. Going with the theme of Thunder Boy. I mean, I've done my best and their mom has done her best to let them find their own name. I think all too often family and tribal tradition is just synonymous with wanting your kid to be like you. Trying to control destiny. And I try not to do that. I'm sure if you asked my kids, they'd tell you I fail, I try.

How old are they now?

18 and 15.

|

|

|

Sherman Alexie takes Thunder Boy, Jr. to the Galloway School in Atlanta, Ga., on May 18, at an event arranged by Little Shop of Stories. |

|

I remember you saying to a crowd of teens in Seattle that books saved your life.

Oh yeah. Well, there's no guaranteed pathway out of poverty, out of social oppression. Nobody around you knows how, nobody has gone that way before. And what you have to start doing is imagining yourself in a different place, imagining yourself as a different person. And the way you begin to do that is to read. I couldn't afford to experience the world. I couldn't go places. So, books were the cheapest, easiest way to transport myself into other people's realities, which enabled me to start thinking about changing my own reality.

What's it been like visiting Native American schools?

I think because my career has become so strange and huge and because I'm on Colbert and stuff, Native people are surprised when they meet me, how Native I am. I think they probably expect me to be much more assimilated. Culturally, racially, geographically. So I think one of the delightful things that happens when I visit Indian schools is when I go into my full-on Indian mode and I sound like their uncles. It narrows the distance between us. It opens up their possibilities. To think somebody who grew up pretty much the way they're growing up now has become who I am. Once they realize how much I am like them I think it gives the stories more power. I love it when anybody reads my books. But when kids like me, when some indigenous kid reads my books and identifies, there is something more powerful about that.

What is your "full-on Indian mode?"

The action, the idioms, everything changes. It's subtle. By and large Natives are not so overtly different from white folks in the way we move through the world. Because there are so few of us, we have far more extensive assimilation skills than a lot of other ethnic groups. Because we don't belong anywhere, with any community. White, brown, black, whatever. We don't belong, so we have to constantly be assimilating. I think we're cultural chameleons. We are spies in the house of ethnicity. Everybody tells us their secrets. And everybody loves us.

That's a good position for a storyteller to be in.

From the right wing to the left wing. We're beloved for all sorts of romantic, stereotypical reasons. There's nothing sadder than a non-Native who actually gets to know us and realizes that we're just as awful as everybody else. We're exactly as awful... and only as good.

You said earlier that people were surprised by how unassimilated you are. That surprises me.

Well, that's because I'm talking to you. And we're speaking in the dominant culture's mode. We're speaking Shelf Awareness vocabulary.

Speaking of that mode, as you well know there's a lot of consciousness-raising going on in the children's lit community--and nationally--about issues of diversity. I read in the Horn Book blog that Mary Hoffman and Caroline Binch's bestselling Amazing Grace was reissued for its 25th anniversary without its original 1991 illustration of an African American girl dressing up as Hiawatha.

Oh wow. That strikes me as going too far. I mean, you either publish the book as it is or you don't publish the book. Oh, man. That strikes me as liberal censorship. What would we say if a conservative press pulled something disturbing to them out of a book, a classic? My response is, don't publish that, publish something new, damn it! With the amount of money they're putting into that book they could probably publish five new books! If you want to pull that Hiawatha image, then why not publish five Native American books with no stereotypical images whatsoever? I am disturbed by the removal of an image from an original book. Even though it's my side of the political fence doing it. But that doesn't mean I have to agree with it. I empathize with the political argument, but it's censorship. I have no more patience with liberal censors than I have with conservative censors.

Does anyone ever approach you about making the Absolutely True Diary movie?

Constantly. Whenever Hollywood starts talking to me I feel like they want me to sign a treaty. I feel very 19th century. And it always seems like such a contradiction. I feel like the most liberal business in the world, Hollywood, is also being the most colonial. I haven't worked there in quite a few years. That contradiction drives me away, keeps me away.

You're on tour with Thunder Boy, Jr. these days. How is it talking to very young children vs. your usual crowd?

It's what I do. I'm a DAD! I've been pointing out backhoes for 18 years now. Backhoe! Backhoe! Bulldozer! Crane! --Karin Snelson, children's & YA editor, Shelf Awareness