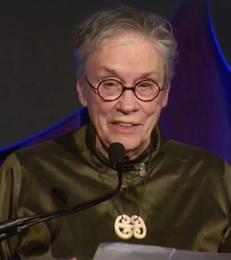

In her acceptance speech for the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters at the National Book Awards last night, author Annie Proulx said:

|

|

| Annie Proulx | |

We don't live in the best of all possible worlds. This is a Kafkaesque time. The television sparkles with images of despicable political louts, sexual harassment reports. We cannot look away from the pictures of furious elements, hurricanes and fires, from the repetitive crowd murders by gunmen burning with rage. We are made more anxious by flickering threats of nuclear war. We observe social media's manipulation of a credulous population, a population dividing into bitter tribal cultures. We are living through a massive shift from representative democracy to something called viral direct democracy, now cascading over us in a garbage-laden tsunami of raw data.

Everything is situational, see-sawing between gut-response likes or vicious confrontations. For some, this is a heady time of brilliant technological innovation that is bringing us into an exciting new world. For others, it is the opening of a savagely difficult book without a happy ending.

To me, the most distressing circumstance of the new order is the accelerated destruction of the natural world and the dreadful belief that only the human species has the inalienable right to life and god-given permission to take anything it wants from nature, whether mountaintops, wetlands, or oil. The ferocious business of stripping the earth of its flora and fauna, of drowning the land and pesticides again may have brought us to a place where no technology can save us.

I personally have found an amelioration in becoming involved in citizen science projects. This is something everyone can do. Every state has marvelous projects of all kinds, from working with fish, with plants, with animals, with landscapes, with shore erosion, with water situations. Yet somehow, the old discredited values and longings persist. We still have tender feelings for such outmoded notions as truth, respect for others, personal honor, justice, equitable sharing. We still hope for a happy ending. We still believe that we can save ourselves and our damaged earth, an indescribably difficult task as we discover that the web of life is far more mysteriously complex than we thought and subtly entangled with factors we cannot even recognize.

But we keep on trying. Because there's nothing else to do. The happy ending still beckons, and it is in hope of grasping it that we go on. The poet Wisława Szymborska caught the writer's dilemma of choosing between hard realities and the longing for the happy ending. She called it consolation.

Darwin. They say he read novels to relax, but only certain kinds, nothing that ended unhappily. If he happened on something like that, enraged he flung the book into the fire. True or not, I'm ready to believe it. Scanning in his mind so many times and places, he's had enough of dying species, the triumphs of the strong over the weak, the endless struggles to survive, all doomed sooner or later. He'd earned the right to have the happy ending at least in fiction, with its microscales. Hence, the indispensable silver lining, the lovers reunited, the families reconciled, the doubts dispelled, fidelity rewarded, fortunes regained, treasures uncovered, stiff-necked neighbors mending their ways, good names restored, grief daunted, old maids married off to worthy parsons, troublemakers banished to other hemispheres, forgers of documents tossed down the stairs, seducers going to the altar, orphans sheltered, widows comforted, pride humbled, wounds healed, prodigal sons summoned home, cups of sorrow tossed into the ocean, hankies drenched with tears of reconciliation, general merriment and celebration, and the dog Fido gone astray in the first chapter turns up barking gladly in the last.