.jpg) |

| Erika Kobayashi Photo: Mie Morimoto |

Erika Kobayashi is the author of Trinity, Trinity, Trinity, translated into English by Brian Bergstrom, which Astra House will publish in June 2022.

There is an almost poetic style in Trinity, Trinity, Trinity—specifically in the use of line breaks, with sentences that might appear in a single paragraph broken up into separate lines. Is this a device to communicate something untranslatable from the Japanese? Or is the original text as unconventional as the U.S. edition?

Brian Bergstrom: Erika's style is both unique to her and builds on tendencies in modern Japanese writing.

Japanese prose tends toward shorter paragraphs and more line breaks than English, especially in its sense of momentum ("thrillers" are usually written in dramatic short graphs, for example). Traditional Japanese poetry is written in a single line (instead of each 5- or 7-syllable unit getting its own line, as in English translations of haiku or waka), and, like prose, it is written vertically on the page. The shortness of poetic verses means that each poem runs down the page and disappears into the white space below, giving the reader a "space" to contemplate each one before moving on to the next.

Erika's use of single-line paragraphs and sentences broken into single-line fragments introduces this poetic effect into her prose, balancing it against the thriller-like pacing of the story overall. The tension between the two effects is a major achievement and something I tried to replicate in my translation.

In the Japanese edition of Trinity, Trinity, Trinity, there is a list of real-world references in the back matter, an unusual feature for works of fiction. Is this common in Japan?

Erika Kobayashi: This is something unusual in Japanese fiction as well, which made me sometimes feel a bit lonely. However, when I encountered the works of Svetlana Alexievich, they gave me great encouragement to go on. Also friends and critics have brought to my attention other writers whose fiction is based on painstaking historical research, including the Japanese American writer Julie Otsuka and the Korean writer Kim Soom. I've derived great inspiration and courage from reading their work as well.

Bergstrom: Frequently, the most surreal-seeming elements of Erika's work are the ones drawn from history. The bibliography allows readers to explore the depth of documentary history lying beneath her prose's poetic, evocative surface.

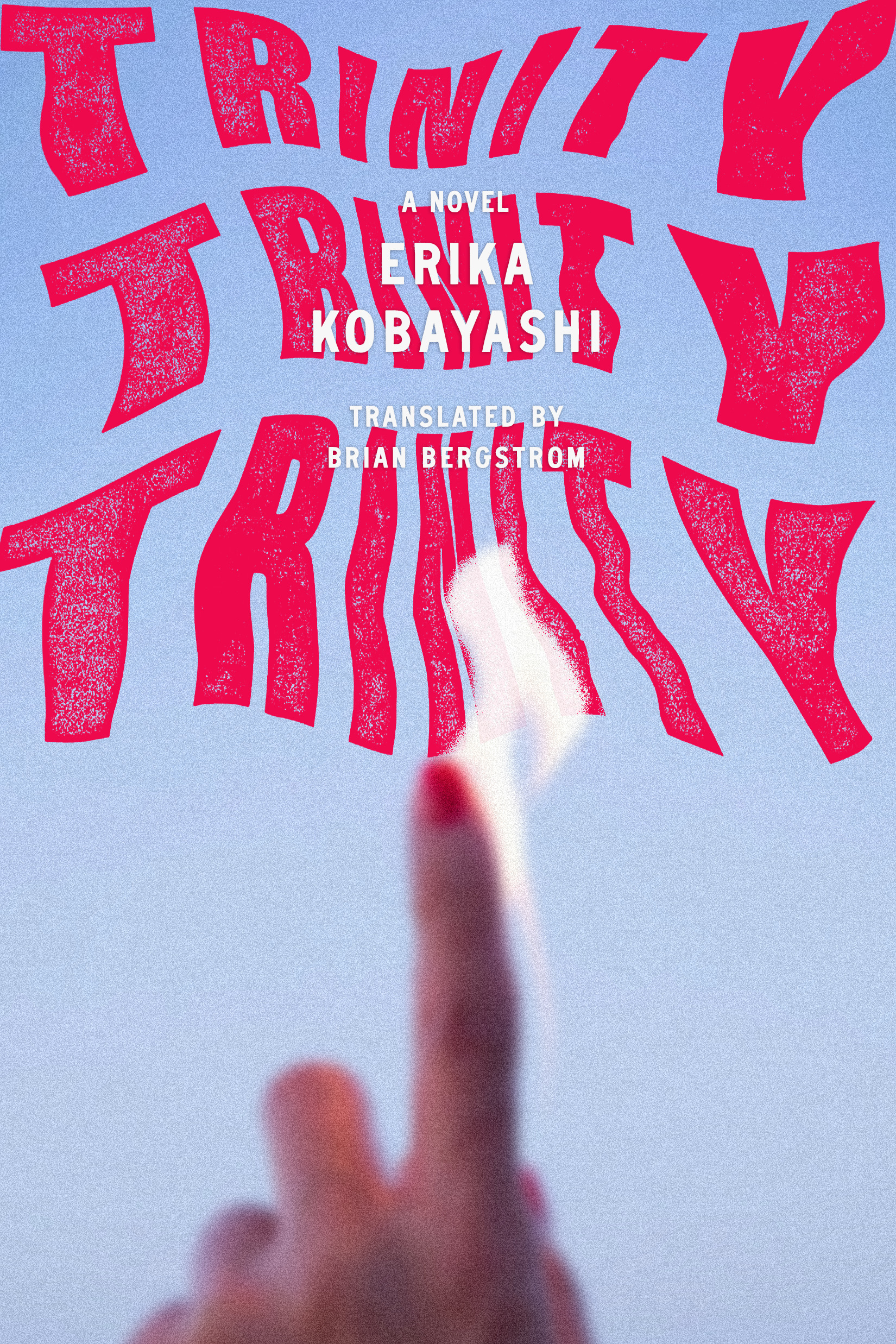

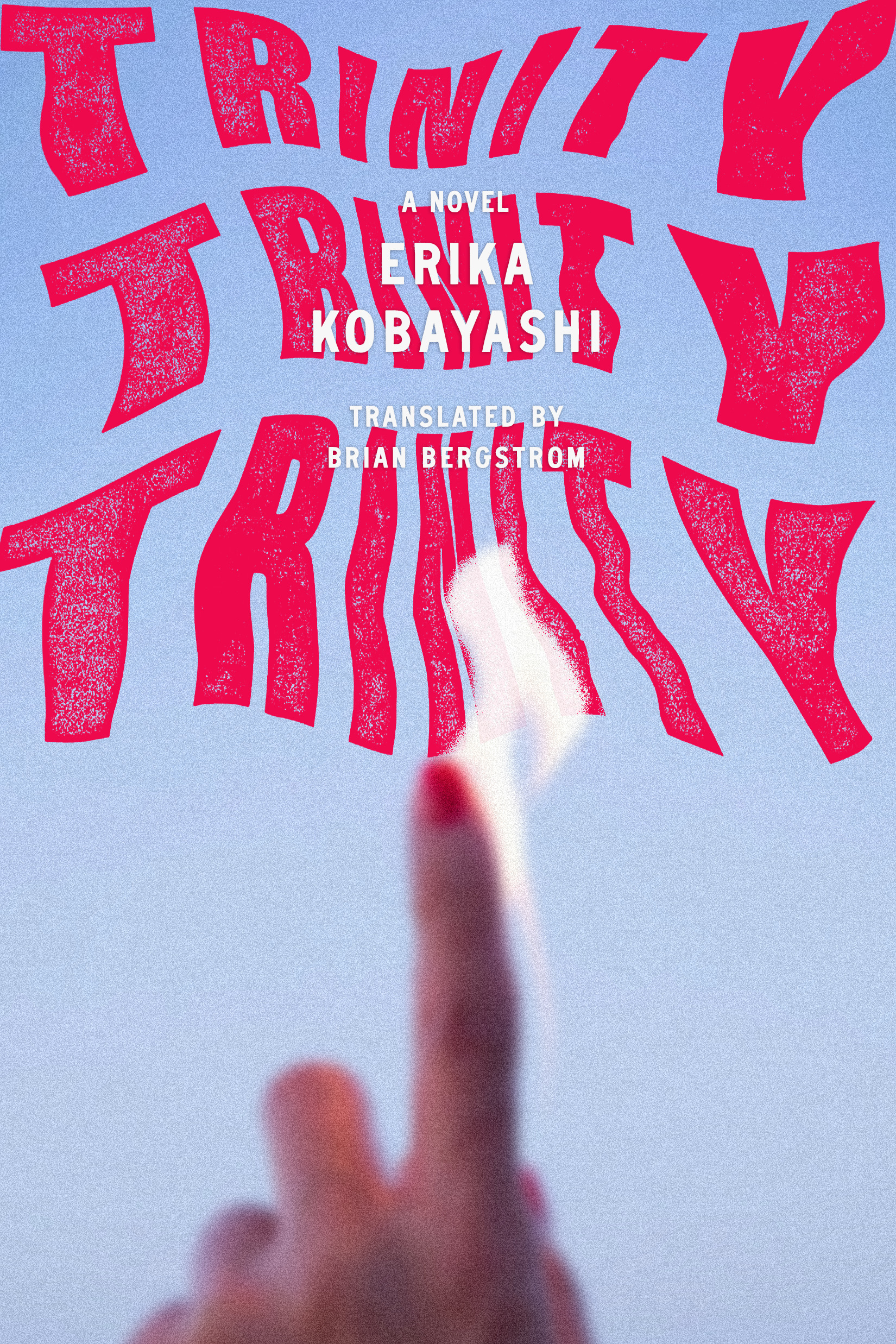

There is a distinct connection between Erika's writing and her visual art practice. Her series of photos titled "My Torch" feature the image of a hand with the tip of the index finger lit aflame. This image is featured on the cover of both the Japanese edition of Trinity, Trinity, Trinity and the U.S. edition. What is the significance of this image?

There is a distinct connection between Erika's writing and her visual art practice. Her series of photos titled "My Torch" feature the image of a hand with the tip of the index finger lit aflame. This image is featured on the cover of both the Japanese edition of Trinity, Trinity, Trinity and the U.S. edition. What is the significance of this image?

Kobayashi: "My Torch" was part of an installation called "She Waited" that was in the group show Image Narratives: Literature in Japanese Contemporary Art at the National Art Center in Tokyo. The exhibition opened in fall of 2019, coinciding with the release of Trinity, Trinity, Trinity in Japanese. I created "She Waited" in tandem with Trinity, Trinity, Trinity, and a visual presentation of it, along with the accompanying text in Japanese and English, are available online at the Chic Magazine website.

Incidentally, the hand in "My Torch" is my hand, and the photograph was taken as I physically lit it on fire. I was inspired by a chemistry experiment described in Richard Feynman's book Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!.

Trinity, Trinity, Trinity takes place at the time of the 2020 Summer Olympics, which were held in Tokyo a year later due to the outbreak of Covid-19. How have the events of the last year affected this? Are there any messages in the book that readers might connect to the upheaval and loss of the last year?

Kobayashi: Seeing Olympic flags all over Tokyo that read "2020" in big letters during the summer of 2021 made me feel like I was living in a piece of science fiction. I've been told by many readers that Trinity, Trinity, Trinity struck them as a kind of prophetic work. People reading it during the time the Olympics actually opened were even more disturbed, saying that it was as if what I'd written had become reality.

Seeing adults and children walking the streets in masks due to COVID-19 reminded me of seeing the same thing happening after the earthquake in 2011. During that time, children from Fukushima faced bullying and discrimination due to concerns that they'd "infect" others with radiation; cars with license plates showing that they were from Fukushima were frequently vandalized. The same thing happened in the COVID-19 era when cars from the Tokyo area were spotted in other parts of Japan.

Bergstrom: Reading and then translating Trinity, Trinity, Trinity over the course of 2020 was a strange experience. Erika's speculative version of the 2020 Olympics incorporates many elements that were "real" in the sense of "really planned," which at the time she wrote it was meant to ground the more fantastical elements in a concrete reality, as well as show how strange that "reality" actually was. But with their postponement, the "real" Olympics as they exist in the novel became the only place they remained.

The postponement of the 2020 Olympics brought to mind the cancelled 1940 Tokyo Olympics, which play an important role in the novel as well; the layering of real and speculative versions of various Olympics through the years is a major part of the novel that only grew more eerily resonant as these newest "real" Olympics became more and more speculative themselves.

Erika's parents were the primary translators of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes novels into Japanese. Did that affect her writing style?

Kobayashi: I grew up in a small house in the Tokyo suburb of Nerima, surrounded by cabbage fields and modest apartment buildings, eating oranges while tucked cozily beneath the blankets of the heated kotatsu table; at the same time, though, it also felt like I was living in 19th-century Victorian London (though I didn't get a chance to visit London until I was in my twenties!).

Watching my mother and father sit at the kitchen table translating Sherlock Holmes stories was, to me as a child, like witnessing magic itself.

Seeing the words of those no longer living come back to life through books struck me as something close to spiritualism (and after all, Arthur Conan Doyle was a devotee of spiritualism himself in the latter part of his life). For this reason, seeing my own words given new life in translation, including Brian's wonderful translation into English, fills me with such joy, as if I'm seeing myself reborn.

With the support of the publisher, Shelf Awareness focuses on Astra House's fall and spring lists, featuring original works of fiction, nonfiction and poetry that expand beyond genre conventions and broaden and deepen our understanding of the world.

With the support of the publisher, Shelf Awareness focuses on Astra House's fall and spring lists, featuring original works of fiction, nonfiction and poetry that expand beyond genre conventions and broaden and deepen our understanding of the world.

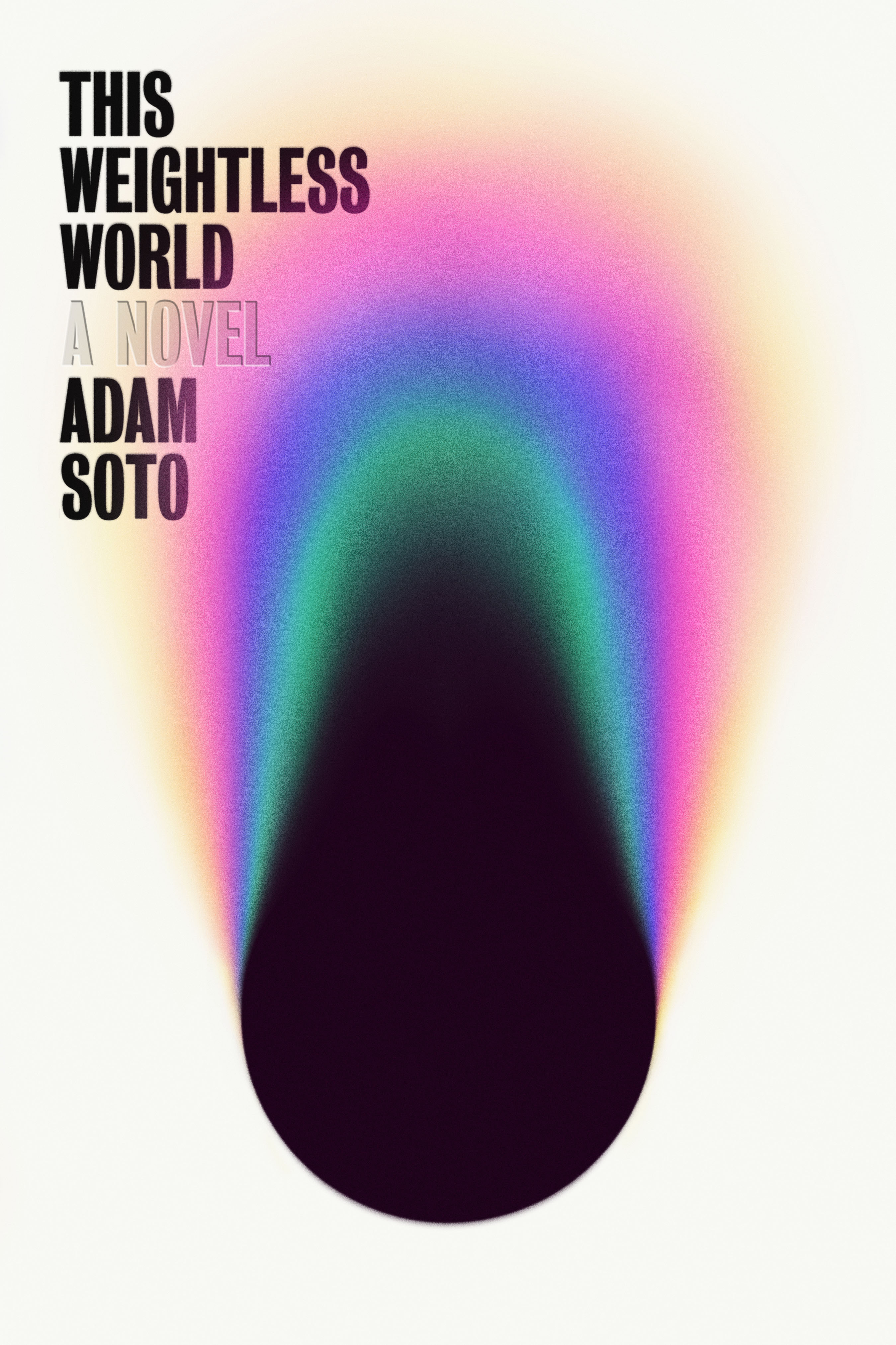

It's the year 2012 in Adam Soto's debut novel, This Weightless World, when a mysterious signal reaches earth from a planet 75 light years away. Initially received as a sign of hope for a technologically advanced future, the signal eventually stops as abruptly as it had started. A classic science fiction trope that typically leads into a story about a war between worlds, here, is instead turned inward, to examine the lives of a revolving cast of characters. Exploring the everyday effects of a supposed cataclysmic, paradigm-shifting event that ends up not really changing much at all, This Weightless World paints an ugly portrait of human exceptionalism and reveals the destructive, paralyzing effects of capitalism, the confusing realities we've created for ourselves, and the reasons we're so often reluctant to break away from them.

It's the year 2012 in Adam Soto's debut novel, This Weightless World, when a mysterious signal reaches earth from a planet 75 light years away. Initially received as a sign of hope for a technologically advanced future, the signal eventually stops as abruptly as it had started. A classic science fiction trope that typically leads into a story about a war between worlds, here, is instead turned inward, to examine the lives of a revolving cast of characters. Exploring the everyday effects of a supposed cataclysmic, paradigm-shifting event that ends up not really changing much at all, This Weightless World paints an ugly portrait of human exceptionalism and reveals the destructive, paralyzing effects of capitalism, the confusing realities we've created for ourselves, and the reasons we're so often reluctant to break away from them. In God of Mercy, Igbo-American author Okezie Nwọka enters into a powerful tradition of magical realist, postcolonial works of fiction. In the novel, we follow the life of Ijeọma and the village of Ichulu, which finds itself at a crossroads, a crisis of warring gods triggered when Ijeoma begins literally to take flight. God of Mercy imagines the condition of African peoples unchanged by external influence into the modern day by way of a village in Igboland that has escaped the exploitation, deprivation, and displacement of colonialism. A celebration of tradition as a marker of cultural identity and an appeal to the value of shifting norms, God of Mercy is a novel about what might become of a people left to design their own future, what conflicts might arise among them as they might have appeared in an alternate timeline.

In God of Mercy, Igbo-American author Okezie Nwọka enters into a powerful tradition of magical realist, postcolonial works of fiction. In the novel, we follow the life of Ijeọma and the village of Ichulu, which finds itself at a crossroads, a crisis of warring gods triggered when Ijeoma begins literally to take flight. God of Mercy imagines the condition of African peoples unchanged by external influence into the modern day by way of a village in Igboland that has escaped the exploitation, deprivation, and displacement of colonialism. A celebration of tradition as a marker of cultural identity and an appeal to the value of shifting norms, God of Mercy is a novel about what might become of a people left to design their own future, what conflicts might arise among them as they might have appeared in an alternate timeline.

The North American edition of your book is publishing in March 2022. What can you tell us about how it differs from the U.K. edition? What are you most excited about when you think about the book being published in the U.S.?

The North American edition of your book is publishing in March 2022. What can you tell us about how it differs from the U.K. edition? What are you most excited about when you think about the book being published in the U.S.?

In The Town of Babylon, one character, the Evangelical minister Paul, is a suspect in a long-unsolved murder. Yet, this isn't a work of crime fiction or mystery. Did you struggle to find a balance between the kind of interior, realist mode in which the novel is written and this pulpier more genre element?

In The Town of Babylon, one character, the Evangelical minister Paul, is a suspect in a long-unsolved murder. Yet, this isn't a work of crime fiction or mystery. Did you struggle to find a balance between the kind of interior, realist mode in which the novel is written and this pulpier more genre element?.jpg)

There is a distinct connection between Erika's writing and her visual art practice. Her series of photos titled "My Torch" feature the image of a hand with the tip of the index finger lit aflame. This image is featured on the cover of both the Japanese edition of Trinity, Trinity, Trinity and the U.S. edition. What is the significance of this image?

There is a distinct connection between Erika's writing and her visual art practice. Her series of photos titled "My Torch" feature the image of a hand with the tip of the index finger lit aflame. This image is featured on the cover of both the Japanese edition of Trinity, Trinity, Trinity and the U.S. edition. What is the significance of this image?

Broken Halves of a Milky Sun

Broken Halves of a Milky Sun Stalking the Atomic City

Stalking the Atomic City Identitti

Identitti