|

|

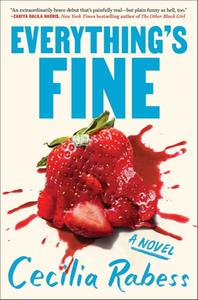

| Cecilia Rabess | |

Cecilia Rabess has worked as a data scientist at Google and an associate at Goldman Sachs. Her nonfiction has appeared in McSweeney's, FiveThirtyEight, Fast Company, and FlowingData, among others. Everything's Fine ($27.99, 9781982187705), which will be published June 6, is her debut novel. The following is an excerpt from the beginning of the book:

1

Jess's first day of work, the first day of the rest of her life. Into the elevator and up to the twentieth floor, where the doors open with a little whoosh.

The entire building smells like money.

She receives a small plaque with her name printed in all caps: JESSICA JONES, INVESTMENT BANKING ANALYST. Then introductions—the other analysts on the team: Brad and John and Rich and Tom, or maybe it's Rich and Tom and Brad and John—and also Josh, who Jess remembers from college.

"Hey," she says, "it's you!"

He looks up from his desk—he is already installed at a workstation, looking busy and important—but his face is blank.

They had a class together last year and Jess remembers him, because he was the worst.

"Jess?" she offers. "From school?" He blinks.

"We had a class together?" she tries again. "Supreme Court Topics?"

He just looks at her, saying nothing. Is it possible she has something on her face?

"With Smithson? Fall semes—"

"I remember you," he says. And then promptly swivels in his chair.

Cool, Jess thinks. Nice catching up.

She starts to go.

"You know," he says, not turning, "I knew you'd been assigned to this desk."

Jess stops. "Oh, really?"

He nods—the back of his head—"I worked with these guys when I was here last summer. And I graduated off-cycle, so I've been back since January." He pauses. "They asked me about you."

"What did you say?"

"Nothing."

"What! Why didn't you tell them I was amazing?"

"Because," he says, finally turning to look at her, "I'm not convinced you are amazing."

—

The first time Jess met Josh, it was fall of their freshman year. November. The night of the 2008 election. All day the campus had pulsated. History in the making. Around eleven the election was called and Jess emerged stunned and delirious onto the quad, which had erupted into something like a music festival. Students spilled out into the night cheering and hugging. Car horns honked. Someone screamed woot woot and, somewhere, a trombone, brimming with pathos, played a slow scale.

The first time Jess met Josh, it was fall of their freshman year. November. The night of the 2008 election. All day the campus had pulsated. History in the making. Around eleven the election was called and Jess emerged stunned and delirious onto the quad, which had erupted into something like a music festival. Students spilled out into the night cheering and hugging. Car horns honked. Someone screamed woot woot and, somewhere, a trombone, brimming with pathos, played a slow scale.

Jess had the feeling she had been shot out of a cannon; she was blinking into the moonlight when a couple of reporters from the school paper stopped her. They were compiling quotes from students on the eve of this historic moment. Did she have a minute to share her feelings, and would she mind if they took her photo? Jess said sure, even though the air was crackling and she wanted to weep.

The reporter's pencil was poised. "Whenever you're ready." What could she possibly say? There were no words.

"I'm just . . . I'm just . . . fucking ecstatic! Is this even real? And now I'm probably going to go have, like, thirty shots—no, fifty!—because that's more patriotic!"

The student reporter looked up from his mini legal pad. "End quote?"

"Wait, no! Don't write that!"

"What do you want to say?"

Jess thought about it, collected herself. Imagined her dad reading her words. Her dad, who she'd spoken to just hours ago, and whose reaction to the early returns—Ohio and Florida were set to break for Obama—was to pour himself another Coke and say: "Well, Jessie, I'll be darned."

She started over. "I feel the weight of history tonight. To cast my very first vote for our nation's very first Black president is such an awesome privilege. A privilege that my ancestors, slaves, did not share. Standing on the shoulders of so much strength and sacrifice, I've never felt more humbled or hopeful."

"That's great," the reporter said. "Now just stand over there and we'll take your shot."

Jess took a step to the left and watched as the reporter approached another student. A sandy-haired freshman wearing chinos and a collared shirt.

The photographer said to Jess, "Look this way. On the count of three."

And the reporter said to the boy in business casual, "How are you feeling about the election?"

Jess turned to the camera and smiled.

The guy in chinos turned to the reporter and said, "Everyone seems to forget that we're in the middle of a financial crisis. The stock market is in free fall. Gas is four dollars a gallon. So I'm not convinced that now is the right time to entrust another tax-and-spend liberal with the economy," he shrugged, "but I guess I can see the appeal."

Jess, aghast, turned to give him a dirty look, her smile dropping just as the flash popped.

The next day she was on the front page of the school newspaper under a headline that read STUDENTS REACT TO OBAMA'S HISTORIC WIN. The picture was good—the angle, the moonlight, her face radiating quiet wonder—and that, plus the gravitas of the moment, made Jess feel like this was something she would show to her children and their children one day.

There was only one problem.

The paper had spoken to ten students, a grid of two-by-two photos and quotes, names and graduation years printed below. But there were only two faces above the fold. There was Jess, but also the guy in the collared shirt, with his terrible quote. Jess's friends agreed that it was a stupid thing to say. Miky, who lived across the hall, said, "Who pissed in his Cheerios?" And Jess's roommate, Lydia, peered at the photo and declared: "He looks boring."

Still, Lydia tacked the paper to the outside of their door. With a marker, she drew a frame of hearts and stars around Jess's face. But there was no way to accordion the paper so that only her picture appeared. It cut off the text strangely and warped her smile. It was impossible to see Jess without seeing Josh. Eventually Miky took a Sharpie and drew devil ears and a weird mustache across his face, and that was better.

Eventually the tack hardened and the paper fluttered to the floor. At that point it was the spring semester and the hallway had devolved into a persistent, low-grade chaos: crushed pizza boxes, twisted extension cords, a mysterious pair of men's underwear. And when the cleaning crew cleared out the dormitory between the spring and summer sessions, they swept everything, including that momentous reminder, into the trash.

But until that happened, Jess could return to her room each day and see the newspaper, like a talisman, stuck to her door, emanating strength and inspiration, and when she looked at it, she would think: We are standing at the precipice of a bright new world, hopeful and resolute, knocking on the door of progress, with the conviction of what's on the other side.

And then she would slide her eyes to the right, to the photo of JOSH HILLYER '12 and his terrible quote, and she would think: Asshole!