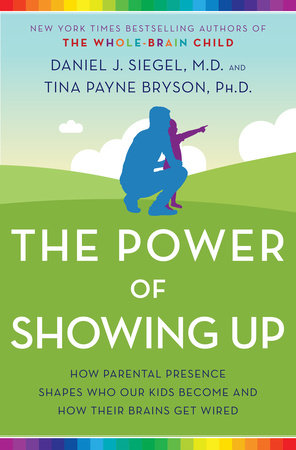

Together, Daniel J. Siegel, M.D., and Tina Payne Bryson, Ph.D., have co-authored three other parenting books: The Whole-Brain Child; No-Drama Discipline; and The Yes Brain. With their latest book, The Power of Showing Up (Ballantine Books, $27), they combine scientific research with no-nonsense guidance to reassure readers that "There's no such thing as flawless child-rearing" and that ideal parenting--creating secure attachment relationships--can be as simple as applying the "Four S's": making a child feel Safe, Seen, Soothed and Secure.

Together, Daniel J. Siegel, M.D., and Tina Payne Bryson, Ph.D., have co-authored three other parenting books: The Whole-Brain Child; No-Drama Discipline; and The Yes Brain. With their latest book, The Power of Showing Up (Ballantine Books, $27), they combine scientific research with no-nonsense guidance to reassure readers that "There's no such thing as flawless child-rearing" and that ideal parenting--creating secure attachment relationships--can be as simple as applying the "Four S's": making a child feel Safe, Seen, Soothed and Secure.

How does The Power of Showing Up vary from your previous titles, and what makes it such a good introduction to the other three?

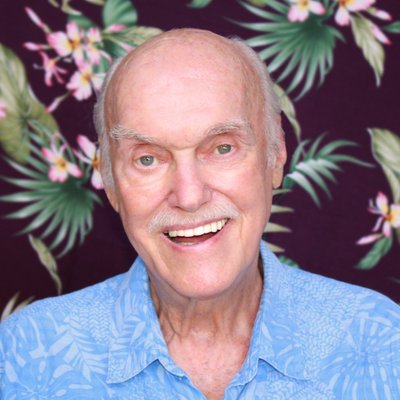

Daniel J. Siegel: The reason we wrote this new book was to offer parents a solid foundation in the art and science of attachment--the ways in which research across cultures reveals the foundations of a parent-child relationship that leads to a child flourishing. It's a fun and grounding book that can serve as the framework for our other works as well.

Tina Payne Bryson: The first three books emphasize many powerful and effective ways caregivers can provide experiences and opportunities, things we can do or teach, to build kids' brains and minds, allowing them to thrive. The Power of Showing Up is also about experiences that build their brains and minds, allowing them to thrive, but it's focused on relational experiences--how we can be as parents, on the quality of our presence, and our relationship with them. It focuses on the one thing our kids need most from us--that we show up--and this book walks with parents to explore how to do that.

|

Dr. Daniel Siegel

(photo: James Reese) |

As the mother of a young toddler, I can certainly speak to the never-ending list of concerns about raising children the "right" way. What is it about the experience of parenting and how we care for our children that makes it such a universally recognizable and sympathetic one?

Siegel: Attachment is how our young become shaped by what we do as parents. Because of this innate human legacy, the universal experiences of parenting involve deeply embedded neural circuits of connection which in turn make it possible to deeply see our kids, have them feel soothed, keep them safe and build the security they need. There is no such thing as "perfect parenting" and so what we try to offer are science-based strategies that are both practical and reflective of the reality that no one ever "gets it right all the time" and that repair is possible so long as we are aware and intentional about it. In fact, it is this kindness toward ourselves that can mobilize our capacity to make a repair more readily. These mismatch-repair-realignment sequences are not only inevitable, but they are what builds resilience in our kids and in our selves.

_Darrell_Walters.jpg) |

Tina Payne Bryson

(photo: Darrell Walters) |

Bryson: As a mom to three, and as a therapist who has listened to many parents, I agree that, at least in our culture, there's a fairly universal experience of fearing we're "not enough" or that we're messing them up, and then that's compounded by the fear and anxiety that come with trying to do it "right." Simply, I think we feel these things because we care so darn much and we want to do right by our children. We know our parents failed us in certain ways, and we want desperately to be the best parents we can be.

One of the reasons I love attachment science is that the research indicates that there is quite a bit of room for parents to be flawed and that we can make a lot of mistakes, but as long as we help our kids feel safe, seen and soothed most of the time, their brains wire to securely know that if they have a need we will see it and show up for them. And when we do that predictably (not perfectly), they learn how to find friends and mates who will show up for them (they come to expect it!), and they learn how to show up for themselves.

Parenting styles and popular methods seem to change with each generation, and many parents worry about too much sensitivity resulting in kids who are "soft" or spoiled. How do you respond to caregivers who worry about spoiling their children or giving them unreasonable expectations of the world?

Siegel: Attuning to our kids involves being able to sense their inner life and respond with compassion and care. The research is quite clear, however, that such attuned connections--coupled with repair of ruptures--builds resilience, not weakness as some may be understandably concerned it might. What we can say to parents is that when a child is seen, safe, soothed and secure, they know themselves well--they don't expect the whole world will be that way for them. This inner knowing, then, has built the capacity to have mutually rewarding relationships, the emotional awareness and equilibrium to take on challenges, have the patience and persistence to move through them and to have a "growth mindset" knowing that the effort they put into something can determine the outcome of their pursuits. That's the stuff of strength, not weakness or being spoiled.

Bryson: The two most heavily researched topics in the childrearing literature are 1) limits/boundaries (also referred to as demand/control) and 2) emotional responsiveness (also referred to as warmth/nurture). Many parents don't know that parenting in sensitive, emotionally responsive, warm and nurturing ways can and should go hand in hand with setting clear, predictable limits and boundaries. We can tune into our child's internal experience and communicate connection and empathy while holding a limit or boundary.

The bottom line is that if you want to raise a kid who is hearty and tough, you should soothe them any chance you get. When you do that, it gives their brain practice going from a reactive state into a regulated state so they can do that for themselves and can handle the hard things that life will inevitably bring. The research doesn't show that kids can get spoiled or become fragile from too much attention or love or affection or nurturing. The research shows that where kids can get "spoiled" is when there are not rules and boundaries that are enforced and they don't get practice respecting limits.

How has technology and the seeming increase in screen time and device usage affected modern-day parenting and relationships?

Siegel: The challenge for all of us is to maintain our face-to-face time of connection and communication. With so many distractions in this digital, mobile age, if we lose these important sources of belonging and understanding in relationships, the art of conversation and the need for self-awareness can become compromised. One big concern is that this impairment in the growth of emotional and social skills will itself produce relational thinness that will make anxiety, depression and despair more prevalent at a changing time in our society when resilience is needed more than ever before.

Bryson: The technology we use can be great and even help us stay connected better if we use it in thoughtful ways. My biggest concern is that we unconsciously reach for [our devices] so often that they pull us away from being present. We are modeling what we value by what we give the most attention to, and my fear is that we're modeling that we value our devices more than our relationships. Our devices can enrich life in certain ways, but I think we can do a much better job of using them as little as possible when we are providing care to children, particularly young ones. One time a stay-at-home mom told me that she worried that she was on her phone too much while she cared for her toddler and asked me, "How much is too much?" I asked her, "If you had a nanny who was caring for your child and he or she was on their device as much as you are, would you feel good about the care your child was receiving?" Her eyes widened and she said, "I'd fire her."

It's important that we are thoughtful about how, when and how much we are on our devices and that we're honest with ourselves regarding how much it interferes with being present with our kids.

You place a significant emphasis on the importance of empathy in child-rearing, both in understanding a child's motivations and in relating one's own experiences to theirs. What are the implications of increased empathy and "showing up," beyond personal relationships, for the next generation as world citizens?

Siegel: The term "empathy" can be defined in many ways. For us, the scientific view of empathy--having at least five interrelated facets--is how we use this term: emotional resonance, perspective-taking, cognitive understanding, empathic joy, and empathic concern. These serve as the gateway in turn for compassion and kindness--compassion being the way we sense suffering, imagine how to reduce that suffering and then take actions to alleviate that suffering. Kindness can be seen as a positive intention to be of benefit to others without expecting anything back in return, a way of being in which we honor and support one another's vulnerabilities. For world citizens, providing an early experience of caregivers who "show up" is the basis for cultivating empathic skills, compassionate states of mind and kindness. Also, moving beyond a solitary sense of self and realizing the importance of the inner self's relational interconnections with other people and with nature--with the planet--may be the crucial shift that the world needs as we move forward as a species.

Bryson: Beautifully said, Dan. I'd just like to add that when we show up empathetically for our children, we are doing something much more than just being nice, more even than regulating their nervous system in the moment to help them calm down. We're stimulating the growth and development of their integrative prefrontal cortex, which allows them, as development unfolds over time, to have greater capacity for problem-solving, insight, empathy, morality, mental and emotional flexibility, creativity, curiosity, decision-making and much more. These qualities of social and emotional intelligence, of wise discernment and of strong executive function to plan and solve are all essential for the world citizens of the next generation. --Jennifer Oleinik, freelance writer and editor

Paragraphs bookstore in South Padre Island, Tex., will close February 29 as co-owners Joni Montover and Griff Mangan have decided to retire. The Monitor reported that for "the past decade, this full-service independent bookstore has been a hub for visitors in search for a variety of new and used books."

Paragraphs bookstore in South Padre Island, Tex., will close February 29 as co-owners Joni Montover and Griff Mangan have decided to retire. The Monitor reported that for "the past decade, this full-service independent bookstore has been a hub for visitors in search for a variety of new and used books."

Pioneer Square,

Pioneer Square, BINC.0325.T2.SUSANKAMILEMERGINGWRITERSPRIZE.jpg)

In

In  "

" Shift: A New Mindset for Sustainable Execution

Shift: A New Mindset for Sustainable Execution Together,

Together,

_Darrell_Walters.jpg)

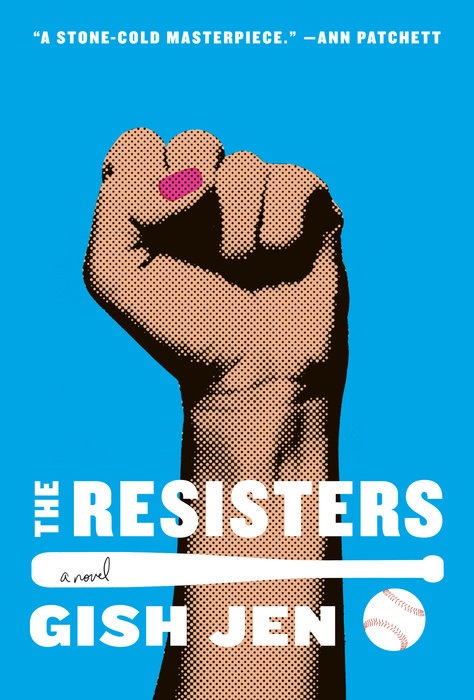

On the list of passions that are as American as apple pie, the game of baseball occupies a prominent place. That's what makes its presence at the heart of Gish Jen's clever dystopian novel The Resisters so meaningful, and so disquieting.

On the list of passions that are as American as apple pie, the game of baseball occupies a prominent place. That's what makes its presence at the heart of Gish Jen's clever dystopian novel The Resisters so meaningful, and so disquieting.