Once considered a small Southern house that specialized in literary, coming-of-age novels by Southern writers, Algonquin has pulled a neat trick: it's come of age itself while retaining the qualities that made it such a lovable  youngster. Algonquin is now a national publisher boasting a range of writers from around the country and abroad; it has its own paperback program; it nurtures and promotes its titles in imaginative, entertaining, effective ways; and it has created strong bonds with booksellers. At the same time, as it has since its founding, Algonquin continues to offer a solid mix of fiction and nonfiction and a standard of writing and storytelling that is remarkably consistent from distinctive book to distinctive book.

youngster. Algonquin is now a national publisher boasting a range of writers from around the country and abroad; it has its own paperback program; it nurtures and promotes its titles in imaginative, entertaining, effective ways; and it has created strong bonds with booksellers. At the same time, as it has since its founding, Algonquin continues to offer a solid mix of fiction and nonfiction and a standard of writing and storytelling that is remarkably consistent from distinctive book to distinctive book.

"Algonquin is the model company of what's right in the industry," said Joe Drabyak of Chester County Book & Music Company, West Chester, Pa. Besides having a good list, he said, "They're exceptional at publicity, advertising and personal sales--creating buzz and handselling."

Becky Anderson of Anderson's Bookshops, Naperville and Downers Grove, Ill., concurred: "They create relationships with us and help us create relationships with our customers. They value what we think and want to know what works for us and what we want to try. They make buying books very attractive with extremely competitive terms and margins. It all goes a long way to building a great business for them and in turn builds a great business for us."

That business began in 1982, when Louis Rubin and Shannon Ravenel founded the house in part because Southern writers had trouble breaking into New York publishing. Authors published in the first years included Clyde Edgerton, Kaye Gibbons, Jill McCorkle and the late Larry Brown. In 1989, Algonquin was bought by Workman Publishing. It maintains its Chapel Hill, N.C., office, although it has some operations at Workman headquarters in the heart of Yankeeland, aka New York City.

Algonquin publishes some 30 titles a year in two seasons, split about evenly between fiction and nonfiction. Offerings include some literary fiction, a debut novel or two, memoirs, cookbooks, a collection of essays and more, on average two books a month, and "each has its own audience and constituency," publisher Elisabeth Scharlatt said. Becky Anderson commented, "It's a small list, but they do so much." (For more on the fall list, see below.)

There are many advantages to having a relatively small list. For one, the staff of 16 knows the list well--not always the case at other houses. "We're contained enough so we can do what we want to do and need to do," Scharlatt said. "We make every book work."

Work them, they do.

In early times, however, some of Algonquin's bestsellers were helped by others, beginning in 1995, when on the front page of the New York Times Book Review, William F. Buckley, Jr., wrote of My Old Man and the Sea: A Father and Son Sail Around Cape Horn by David Hays and Daniel Hays: "The account of the passage, related in alternating sections by father and son, will be read with delight 100 years from now." After that, My Old Man and the Sea had full sales.

In 1997, Oprah picked Ellen Foster and A Virtuous Woman, both by Kaye Gibbons, for her book club--and of course huge sales followed. In 2000, lightning struck again: Oprah picked Gap Creek by Robert Morgan. And Good Morning America helped boost Lee Smith to fame, picking The Last Girls for its book club.

But who needs Oprah when your company has developed the kinds of relationships that make some booksellers seem to be an extension of the publishing house?

In the past several years Algonquin has had three homegrown bestsellers: Water for Elephants by Sara Gruen, Mudbound by Hillary Jordan and A Reliable Wife by Robert Goolrick. And in the past year, Algonquin placed six books on the New York Times bestseller list. These achievements--and increasing sales throughout the list--come "from the momentum we create early on for a book," marketing director Craig Popelars said. Or, as publicity director Michael Taeckens noted, "We never stop talking about the books. We never stop promoting them."

"Once the manuscripts come in, we all read them, and Craig and I strategize and figure out how to run with these different titles," Taeckens continued. "We're always trying to think of something that's new and fun and different that will attract people's attention. We can't always do giveaways with galleys, but we always try to inject some personality into the press materials and avoid bland corporate speak."

"Peter [Workman] and Elisabeth have never been constrained about how we promote a book," Popelars added. "The philosophy is that if you feel it will sell books, just do it."

The other important aspect of promotion is having fun. As Popelars said, "If we're not entertained, who will be?"

Becky Anderson, whose stores have done many programs with Algonquin, attested to the approach's effectiveness. "They're always successful," she said. "We always have fun and our customers have fun. And we sell a lot of books. There's nothing like the humor they bring to our business."

Among the company's typical and amusing promotions and marketing efforts:

In 1998, the house promoted Running North by Ann Mariah Cook, about a New Hampshire family's entry into the Yukon Quest, by hosting a dogsled run between two New Hampshire bookstores.

For An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England, the 2007 novel by Brock Clarke, Algonquin staged a letter-writing campaign about house torching that led police to make inquiries--and had to be shut down quickly. Despite "a little bit of negative attention," as Taeckens put it, "we got an amazing outpouring of review attention, probably more than for any other novel we've published. I heard from so many people who thought it was a hoot."

Taeckens's all-time favorite campaign, he said, was for Candyfreak: A Journey Through the Chocolate Underbelly of America by Steve Almond, "a funny and nostalgic memoir" about smaller candy companies and their history that was published in 2004. Algonquin contacted the seven companies profiled in the book and received "hundreds of boxes of candies" to give as samples with galleys to the media. "It went over extremely well," Taeckens said. "People reminisced about candy bars" that had either disappeared or were hard to find. "I heard from so many people."

Not only does promotion start long before it does at many other houses, it continues long after. For example, Heidi Durrow's The Girl Who Fell from the Sky was published at the beginning of the year, but she is "still on tour, still getting publicity," Taeckens said. "We're getting requests for interviews and appearances. We're still promoting it as much now as we were in January."

In the same way, Algonquin continues to pay attention to backlist. "Peter Workman is a pitbull about backlist," Popelars said. "Once he sinks his teeth into a book, he doesn't let go. A given title might be backlist, but we treat it like frontlist and pound and pound away."

"It's a lesson from Workman," Scharlatt said. "Don't give up on a book. It's not just for this season."

Among Algonquin backlist gems, Scharlatt cited Educating Esme by Esme Raji Codell, the diary of a teacher's first year teaching in inner-city Chicago. When the MS arrived, Scharlatt remembered, "I thought, 'Just what the world needs. Another teacher memoir.' " But she "laughed and cried," and now, 11 years, 200,000 copies and three editions later, "It's one of the classic books about teaching."

Popelars called Last Child in the Woods by Richard Louv--which argues that exposure to nature is essential for a child's healthy development--"the most important book we've published. It changed the way people think about raising their children."

Just as Algonquin might change how people think about raising its book children.

Starting with Water for Elephants, which was published in 2006, Algonquin has developed a formal paperback program and now retains paperback rights for many of its titles. Earlier it published some paperback titles, but usually sold paperback rights to other houses. The program helps the list as a whole and, among other advantages, results in more book club adoptions of Algonquin titles, which are popular with reading groups. And to help paperbacks with book club potential, the company publishes some titles as Algonquin Readers Roundtable editions, which have readers' guides, author interviews and other special features.

Starting with Water for Elephants, which was published in 2006, Algonquin has developed a formal paperback program and now retains paperback rights for many of its titles. Earlier it published some paperback titles, but usually sold paperback rights to other houses. The program helps the list as a whole and, among other advantages, results in more book club adoptions of Algonquin titles, which are popular with reading groups. And to help paperbacks with book club potential, the company publishes some titles as Algonquin Readers Roundtable editions, which have readers' guides, author interviews and other special features. Most likely to knock your teeth out in a bar fight: Joe by Larry Brown

Most likely to knock your teeth out in a bar fight: Joe by Larry Brown West of Here by Jonathan Evison, due in early February, was one of the books discussed at BEA's Editors' Buzz panel; it's a favorite of Algonquin editor Chuck Adams.

West of Here by Jonathan Evison, due in early February, was one of the books discussed at BEA's Editors' Buzz panel; it's a favorite of Algonquin editor Chuck Adams. A Curable Romantic by Joseph Skibell, coming in September, is "a huge sweeping novel that covers 50 years of European history and is funny, and character driven," Scharlatt said. Beginning in Vienna in 1895, the book is narrated by Dr. Jakob Sammelsohn, who was raised in a tiny Polish village and married twice, divorced in one case and widowed in the other--at the age of 12. Sammelsohn meets Dr. Sigmund Freud, who is just building his practice, and is smitten by Emma Eckstein, one of Freud's most famous and earliest patients.

A Curable Romantic by Joseph Skibell, coming in September, is "a huge sweeping novel that covers 50 years of European history and is funny, and character driven," Scharlatt said. Beginning in Vienna in 1895, the book is narrated by Dr. Jakob Sammelsohn, who was raised in a tiny Polish village and married twice, divorced in one case and widowed in the other--at the age of 12. Sammelsohn meets Dr. Sigmund Freud, who is just building his practice, and is smitten by Emma Eckstein, one of Freud's most famous and earliest patients. Blind Your Ponies by Stanley Gordon West is about a high school basketball team in a rundown town in Montana and the English teacher who coaches them. After two stars come to town, the team rebounds. West published the book himself and sold more than 40,000 copies "out of his trunk," Popelars said. "Our Pacific Northwest rep kept hearing about it and the rep's mother heard a reading"--the rest is history.

Blind Your Ponies by Stanley Gordon West is about a high school basketball team in a rundown town in Montana and the English teacher who coaches them. After two stars come to town, the team rebounds. West published the book himself and sold more than 40,000 copies "out of his trunk," Popelars said. "Our Pacific Northwest rep kept hearing about it and the rep's mother heard a reading"--the rest is history. Nothing Left to Burn by Jay Varner is a memoir of a family that includes a fire chief father and arsonist grandfather. Find some enlightment through this

Nothing Left to Burn by Jay Varner is a memoir of a family that includes a fire chief father and arsonist grandfather. Find some enlightment through this  A 2008 Giller Prize finalist, Barnacle Love by Anthony De Sa is a series of stories that "fit together and add up to a novel," Scharlatt said. The tale follows two generations of fishermen who emigrate from Portugal to Canada, "a wonderfully portrayed immigrants' story."

A 2008 Giller Prize finalist, Barnacle Love by Anthony De Sa is a series of stories that "fit together and add up to a novel," Scharlatt said. The tale follows two generations of fishermen who emigrate from Portugal to Canada, "a wonderfully portrayed immigrants' story." The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey has led to an addition in Algonquin staff: Snookie and The Situation, two snails who are teaching the staff all about the lives and ways of Gastropoda. Read more about them via senior publicist Kelly Bowen's

The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey has led to an addition in Algonquin staff: Snookie and The Situation, two snails who are teaching the staff all about the lives and ways of Gastropoda. Read more about them via senior publicist Kelly Bowen's  Land sakes alive. Reflecting Algonquin's more national approach, the annual New Stories from the South, in its 25th anniversary edition this year, will continue to focus on work by Southerners across the country, but for the first time the guest editor is from the North: Amy Hempel.

Land sakes alive. Reflecting Algonquin's more national approach, the annual New Stories from the South, in its 25th anniversary edition this year, will continue to focus on work by Southerners across the country, but for the first time the guest editor is from the North: Amy Hempel.

Like his actor brother Zach (Scrubs, Garden State), Josh Braff is a music aficionado, and his novel cries out for a soundtrack that captures the seediness and counterculture of New York City in the 1970s. We asked Josh to create a Peep Show soundtrack, and here's what he came up with:

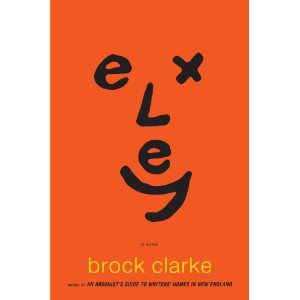

Like his actor brother Zach (Scrubs, Garden State), Josh Braff is a music aficionado, and his novel cries out for a soundtrack that captures the seediness and counterculture of New York City in the 1970s. We asked Josh to create a Peep Show soundtrack, and here's what he came up with: You got rave reviews for An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England--the New York Times, People, USA Today, Entertainment Weekly, the Los Angeles Times, Boston Globe, Washington Post and many more. How did you feel about following that big act with Exley, which publishes in October?

You got rave reviews for An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England--the New York Times, People, USA Today, Entertainment Weekly, the Los Angeles Times, Boston Globe, Washington Post and many more. How did you feel about following that big act with Exley, which publishes in October? Does a reader have to be familiar with Frederick Exley's A Fan's Notes to enjoy or understand your book?

Does a reader have to be familiar with Frederick Exley's A Fan's Notes to enjoy or understand your book? Caroline Leavitt is the author of eight novels and is a columnist for the Boston Globe, a book reviewer for People and a writing instructor at UCLA online. Pictures of You, which will appear as a trade paperback original from Algonquin in January, is the story of two women running away from their marriages who collide on a road on a foggy night. One woman is killed, and the survivor, along with the husband and son of the dead woman, tries to make sense of where that woman was running and why.

Caroline Leavitt is the author of eight novels and is a columnist for the Boston Globe, a book reviewer for People and a writing instructor at UCLA online. Pictures of You, which will appear as a trade paperback original from Algonquin in January, is the story of two women running away from their marriages who collide on a road on a foggy night. One woman is killed, and the survivor, along with the husband and son of the dead woman, tries to make sense of where that woman was running and why. On your nightstand now:

On your nightstand now: