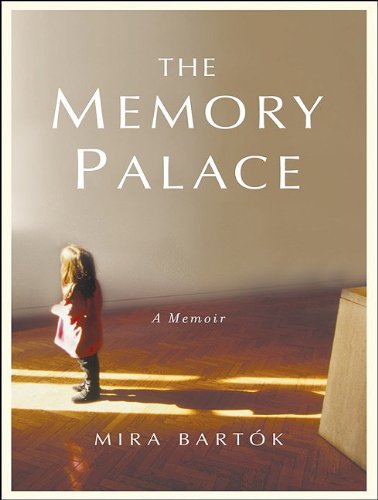

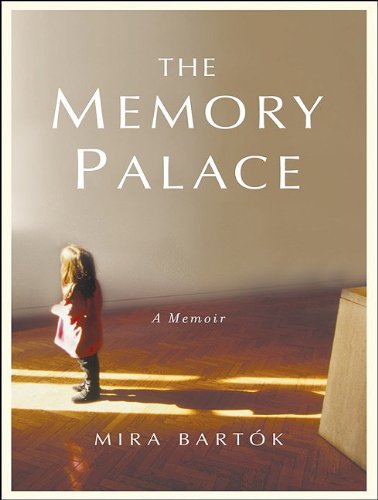

Mira Bartók's compelling memoir opens with this epigraph: "Child, knowledge is a treasury and your heart its strongbox." Bartók has gathered knowledge her entire life, and kept it in her heart as talisman and anchor; in The Memory Palace, she opens her heart and shares the story of her schizophrenic mother, Norma, and what she and her sister, Natalia, had to do to survive life with, and without, a severely sick woman.

Mira Bartók's compelling memoir opens with this epigraph: "Child, knowledge is a treasury and your heart its strongbox." Bartók has gathered knowledge her entire life, and kept it in her heart as talisman and anchor; in The Memory Palace, she opens her heart and shares the story of her schizophrenic mother, Norma, and what she and her sister, Natalia, had to do to survive life with, and without, a severely sick woman.

"A homeless woman, let's call her my mother for now, or yours, sits on a window ledge in late afternoon, in a working-class neighborhood in Cleveland or it could be Baltimore or Detroit. She is five stories up, and below the ambulance is waiting, red lights flashing in the rain. The woman thinks they're the red eyes of a leopard from her dream last night. The voices below tell her not to jump, but the ones in her head are winning."

Mira and Natalia grew up in Cleveland with their divorced mother and her parents, who lived a few blocks away. Norma Herr, who was a piano prodigy with a glittering future, began to fall apart early in her marriage, and her husband left when the girls were young. The girls--then named Myra and Rachel--had a difficult and frightening life, made worse by a brutal grandfather and ineffectual grandmother; in their 30s, in order to escape their mother's relentless pursuit, they changed their first and last names. They were terrified--"She was the cry of madness in the dark, the howling of wind outside our doors...."--and it was necessary, because their mother was extremely resourceful, at one point even hiring a detective to find them.

For 17 years, Mira did not see her mother, but communicated through a PO box address. When she at last found the strength and the desire to see her, Norma was dying.

When Mira went to see her mother, it was a journey filled with more than reunion anxiety: in 1999, Mira sustained a major brain injury in an automobile accident, and still has trouble with her memory and the bombardment of stimuli, like a car radio, or bright lights, or many voices. On a good day, she can act like normal and sound articulate, but she keeps an on-going inventory of what she's afraid she'll forget, her computer is covered with Post-its, and her "life has become a palimpsest--a piece of parchment from which someone had rubbed off the words, leaving only a ghost image behind."

Mira wonders what to take to Cleveland--what would she bring to show her mother the last 17 years of her life? Reindeer boots from when she lived in the Arctic? A petfrified bat or mouse skeleton from her studio? Star charts, bird charts, paintings, maps? She dreams about bringing her mother back to her home, where Norma could die surrounded by plants and books and music, but she knows that won't happen. She asks, "How will I remember her, after she is gone?" If this were the entire story, told in narrative, it would be gripping enough. What sets it apart is Mira Bartók's journey into the chaos of deep memory, her honesty and compassion, and her artist's soul.

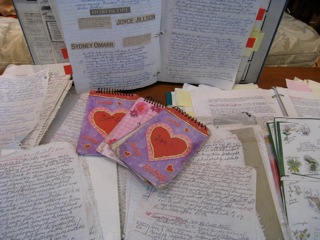

At the hospital, Mira finds, among other things, a sock filled with 17 keys and a diary--her mother kept diaries all her life. She had been studying geology; before that, Edgar Allen Poe; before that, the stars: "Recently, I had a dream of a cataclysm. Was not prepared for study of the planets, which has fevered my imagination once again."

Mira had also been studying geology, reading a book about Nicolaus Steno, the 17th-century Danish father of geology. "My mother would have loved [him]. She'd marvel at the way his mind flew from one thought to another, uncovering the truth about ancient seas, how he learned to read the memory of a landscape, one layer at a time.... If my mother were well enough, I would tell her this. She'd light up a cigarette, pour herself a cup of black coffee, and get out her colored pens. The she'd draw a giant chart with a detailed geological timeline, revealing the stratifications of the earth."

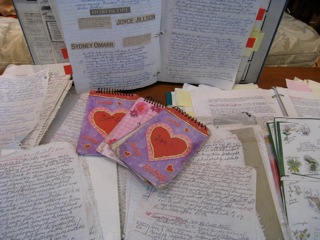

Her sister, Natalia, joins her in Cleveland, where, for one last time, for Norma, they'd be Myra and Rachel. There, they find her storage locker, and unlock the door to the past decades--furniture, trash, cans of soup, a butcher knife. Natalia wonders if that was the one Norma had when the police caught her at Logan Airport. "I'm sure she was on her way to find me." Newspaper articles, children's books, 13 pairs of scissors (Norma had tried to slit her wrists with cutting shears after her divorce), stacks of drawings and a huge box of notebooks devoted to her eclectic research: geometry, poetry, chemistry, the Bible, medicine, botany, fairy tales. For each subject she made vocabulary lists, something Mira would have done before her brain injury. "Her files could have been my files; her notes, mine."

Her sister, Natalia, joins her in Cleveland, where, for one last time, for Norma, they'd be Myra and Rachel. There, they find her storage locker, and unlock the door to the past decades--furniture, trash, cans of soup, a butcher knife. Natalia wonders if that was the one Norma had when the police caught her at Logan Airport. "I'm sure she was on her way to find me." Newspaper articles, children's books, 13 pairs of scissors (Norma had tried to slit her wrists with cutting shears after her divorce), stacks of drawings and a huge box of notebooks devoted to her eclectic research: geometry, poetry, chemistry, the Bible, medicine, botany, fairy tales. For each subject she made vocabulary lists, something Mira would have done before her brain injury. "Her files could have been my files; her notes, mine."

"There was danger imparted to me at birth." Norma writes about her father threatening to kill her with a lamp. Some years later, at the dining table in front of the girls, he yells: "Eat the lamb! I cook all day for you whores. Now eat!" Norma says in a small voice that she's not hungry. He gets a gun, holds it to Norma's head and says, "Nobody leaves this room until you eat that lamb." Hours later, he falls asleep and Norma is still sitting at the table, fork in one hand, cigarette in the other. She stares at Myra and says, "There are those who wish us dead."

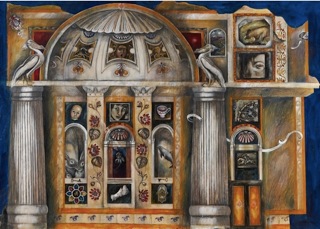

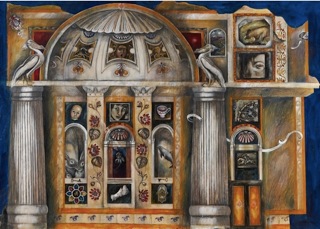

As Mira remembers her life, she asks, "Who am I, then, if my memory is impaired?" Old memories feel trapped in amber, and yet the part of her brain that stores museum artifacts--fossils, masks, bones--and everything else she loves to look at and draw is, for the most part, intact. If she can find the right pictures, perhaps they will lead her to the core. Memory is associative. Her mother built a memory cabinet at the storage unit; could Mira build one too? A memory palace? She starts with a photo, a close-up of her mother taken in 1959. Her face looks soft in the photograph. What can't be told from the picture is that Norma tried to fly out a second-floor wind soon after it was taken. The next picture, which Mira "hangs" across from Norma, is of Caravaggio's Medusa. Myra is in her bedroom one day when she hears a low guttural sound, followed by strange chattering and laughter. She follows the sound and sees her mother, stumbling in her underwear, spinning around with a knife in her hand, obscenities rolling off her tongue. "My sweet beautiful mother merges with Medusa."

As Mira remembers her life, she asks, "Who am I, then, if my memory is impaired?" Old memories feel trapped in amber, and yet the part of her brain that stores museum artifacts--fossils, masks, bones--and everything else she loves to look at and draw is, for the most part, intact. If she can find the right pictures, perhaps they will lead her to the core. Memory is associative. Her mother built a memory cabinet at the storage unit; could Mira build one too? A memory palace? She starts with a photo, a close-up of her mother taken in 1959. Her face looks soft in the photograph. What can't be told from the picture is that Norma tried to fly out a second-floor wind soon after it was taken. The next picture, which Mira "hangs" across from Norma, is of Caravaggio's Medusa. Myra is in her bedroom one day when she hears a low guttural sound, followed by strange chattering and laughter. She follows the sound and sees her mother, stumbling in her underwear, spinning around with a knife in her hand, obscenities rolling off her tongue. "My sweet beautiful mother merges with Medusa."

"Sign of Mars. Dreamless nights. Sunshine, continued cool.... Must think of something to control rage. Birth flower, May, lily of the valley.... Think of something cheerful: a sweet pea. Draw a picture of it."

After Medusa arrived, she never left for good. On days of agitated pacing, Myra and Rachel stayed out of her way or went to their grandparents' and played in the gardens among the fruit trees. If things got worse, she told herself, she and Rachel could live in a wolf den in the middle of the woods. Her mother continued to be admitted into hospitals for short stays, diagnosed as catatonic, dissociative, delusional, hysterical, mad.

"Sometimes in my dreams I am taken out of the city to a place where they monitor the hearts of Jews and other marginalized citizens. Recently, I discovered I was given a pacemaker without consent."

Their mother's change from neglect to unremitting intrusion was gradual, and seemed to begin when Rachel started fussing with her hair and flirting with boys at school. In public she shouted out questions: "Who are you sleeping with? Are you menstruating yet? Is that sperm on your leg? Pull up your skirt and let me see." Or she would ride a bicycle to the girls' school, circle the grounds, ring the bike bell, and call their names over and over. "Where are my children? Someone has kidnapped my children!" Is that when Rachel and Myra started heaving the dresser against the bedroom door at night?

Their mother's change from neglect to unremitting intrusion was gradual, and seemed to begin when Rachel started fussing with her hair and flirting with boys at school. In public she shouted out questions: "Who are you sleeping with? Are you menstruating yet? Is that sperm on your leg? Pull up your skirt and let me see." Or she would ride a bicycle to the girls' school, circle the grounds, ring the bike bell, and call their names over and over. "Where are my children? Someone has kidnapped my children!" Is that when Rachel and Myra started heaving the dresser against the bedroom door at night?

"Baron: an air-cooled gas operated machine gun that uses 303 caliber ammo, fired from the shoulder. I can think of a few men I'd like to use that baby on. B is for babies: where did my little girls go?"

When Rachel leaves for college (after thwarting her mother's attempts to destroy her acceptance letters), Myra wonders how heavy a dresser is when only one is pushing it against a door? When she leaves a year later for art school in Chicago, she's constantly afraid that her mother will show up at her apartment, at school, at work. Her sense of stability comes from making art and working in museums; in particular, the Field Museum is her "salvation and sanctuary." When her mother's calls get to be too much, she chants lists of birds and plants. But one day her mother comes to the museum, saying everywhere she looks they have a gun pointed at her head.

It wasn't until 1990 that Myra finally sent her a letter with a PO box number, lying and saying she had moved to another neighborhood. Her mother wrote back immediately--she would track her down and save her from the kidnappers. Myra and Rachel tried to get a court to declare her incompetent, but no--she could still cash her disability checks and manage a checking account; ergo, she was competent. In late January of that year, Myra and Rachel went to their mother's to try to convince her to sign guardianship papers. Norma smashed a bottle against the table and came after them. Struggling with Myra, Norma cut her daughter's neck with the broken bottle. Myra and Rachel managed to get away as Norma ran after them, shouting, "I'm your mother! Come back!"

Later that year, Myra moved to Italy. "Without my sister and family around to remind me that she is the writer and I am the artist, I start writing stories and poems. I don't want to be the person who gasps in fear whenever she hears the sound of a doorbell or a phone. I just want to lose myself in these hills, in the river winding west to the city of bridges." When she goes back to Chicago, she changes her name to Mira Bartók after signing a contract for a children's book series and realizing her mother could track her that way. She was as safe as she could be, and yet, safety still eluded her, from her time in Israel when a soldier stalked her to her life with her first husband, who was a moody, manipulative poet. She longed to be far away, in a place no one knew, and dreams, "Someday I will live in a quiet green place, off a winding country road. My house will be small but warm, and the rooms awash with light. The floor will be terra-cotta red.... Outside, I will have a small, enclosed garden, dense with vegetables and flowers.... And if I look out the window at just the right moment, the garden will be illuminated in the golding hour of the day."

Later that year, Myra moved to Italy. "Without my sister and family around to remind me that she is the writer and I am the artist, I start writing stories and poems. I don't want to be the person who gasps in fear whenever she hears the sound of a doorbell or a phone. I just want to lose myself in these hills, in the river winding west to the city of bridges." When she goes back to Chicago, she changes her name to Mira Bartók after signing a contract for a children's book series and realizing her mother could track her that way. She was as safe as she could be, and yet, safety still eluded her, from her time in Israel when a soldier stalked her to her life with her first husband, who was a moody, manipulative poet. She longed to be far away, in a place no one knew, and dreams, "Someday I will live in a quiet green place, off a winding country road. My house will be small but warm, and the rooms awash with light. The floor will be terra-cotta red.... Outside, I will have a small, enclosed garden, dense with vegetables and flowers.... And if I look out the window at just the right moment, the garden will be illuminated in the golding hour of the day."

In Mira's quest for safety and wellbeing, she and her sister mirror Norma's determination and strength to choose freedom and a creative life. If they had stayed in Norma's orbit, they would have had to give up their lives for her, "and our art, the two things she taught us to hold most sacred and dear." There was great love and sweetness in their mother, but schizophrenia devoured it every day.

A memoir about living with a schizophrenic mother could have turned out to be "just" a horrifying story, and yet, in telling it, Bartók--even through narrow escapes and traumatic occurrences--has told a story of the deep, mystical bond between a daughter and a mother, and their quest for freedom and autonomy. Bartók has great compassion for the beautiful, brilliant, obsessed mother who lived with the voices in her head but was still determined to live.

"If I had another life as the person I was supposed to become, I'd go to France and sit at a red table and look out the window at blue and green waves. Someone who wasn't in hiding would serve me cheese Danishes and coffee without arsenic."

Bartók says our brains are built not to fix memories in stone but rather to transform them; our recollections change in the retelling of them. How often do we think about this when reading memoirs? How often do we realize this in ourselves? With memoirs, we hope to get a larger, universal truth, the kind we often encounter in fiction, because facts are mutable. And part of that truth will hold mystery, like Norma's madness and intelligence. Centuries ago, Nicolaus Steno said, "Beautiful is what we see. More beautiful what we understand. Most beautiful what we do not comprehend." Within the mystery of love and bond and fear--"When I think of my mother beating her cold white fists against our flimsy door.... I don't know whether to kill her or to take her in my arms and sing her to sleep."--Mira Bartók has found beauty and peace. --Marilyn Dahl

How difficult was it to write your

memoir? When it ends, your memory is still a problem for you.

How difficult was it to write your

memoir? When it ends, your memory is still a problem for you. The order,

the beauty, the sense of possibility. The idea that there was this endless,

endless shelf of books, this endless hall of paintings.... I mean, there's

something about that. And there's something about the natural world. Both my

sister and I spend a lot of time outside--we were what you called outside girls

growing up. We were outside constantly and we still are. We both have dogs and

we spend a lot of time outdoors. We grew up in the city, but at my

grandparents' we had this wonderful field and we were really close to the Rocky

River Park--acres and acres of trails and creeks, and horses you could ride--it

was pretty extraordinary. Kind of this other world I could be in rather than home.

If I hadn't had that contact with the natural world, as well as the books and

paintings, I'm not sure what would have happened.

The order,

the beauty, the sense of possibility. The idea that there was this endless,

endless shelf of books, this endless hall of paintings.... I mean, there's

something about that. And there's something about the natural world. Both my

sister and I spend a lot of time outside--we were what you called outside girls

growing up. We were outside constantly and we still are. We both have dogs and

we spend a lot of time outdoors. We grew up in the city, but at my

grandparents' we had this wonderful field and we were really close to the Rocky

River Park--acres and acres of trails and creeks, and horses you could ride--it

was pretty extraordinary. Kind of this other world I could be in rather than home.

If I hadn't had that contact with the natural world, as well as the books and

paintings, I'm not sure what would have happened.  In your memoir, you say, "Someday

I will live in a quiet green place, off a winding country road. My house will

be small, but warm...." Do you have that now?

In your memoir, you say, "Someday

I will live in a quiet green place, off a winding country road. My house will

be small, but warm...." Do you have that now? ill, and I never saw her behavior as cruel; her obsession was

the product of someone who was really ill. I even have a problem with the word "mad"

or "madness." I use that word in the book, but it's a word that not

everyone in the mental health community likes. I just tried to be careful not

to perpetuate the idea that schizophrenics are really violent, because most of

them are not, and most of the time my mother was not, she was just obsessed--she

really believed she had to protect her daughters from the world, from imaginary

enemies. It's not like she tried to keep us locked in the house because she was

cruel--no, she was sick. I knew she was sick from very early on, I knew it wasn't

intentional, like she was evil. But some people read the book and are amazed

that I can forgive her for being so cruel. No, she was sick, I say over and

over, this is an illness, we need to treat it, we need to take it seriously.

But there's still that lingering thing in society that says mentally ill people

are crazy and evil, and they're not. That's a pet peeve. That's something that

surprised me. Is it the fault of my writing? I hope not; my hope is that people

will see my mother and people who suffer from mental illness in a more

compassionate way, and see people who live on the street more compassionately.

I hope that at the heart of this book lies compassion, and that readers can

find that in themselves. But you can't control how people read.

ill, and I never saw her behavior as cruel; her obsession was

the product of someone who was really ill. I even have a problem with the word "mad"

or "madness." I use that word in the book, but it's a word that not

everyone in the mental health community likes. I just tried to be careful not

to perpetuate the idea that schizophrenics are really violent, because most of

them are not, and most of the time my mother was not, she was just obsessed--she

really believed she had to protect her daughters from the world, from imaginary

enemies. It's not like she tried to keep us locked in the house because she was

cruel--no, she was sick. I knew she was sick from very early on, I knew it wasn't

intentional, like she was evil. But some people read the book and are amazed

that I can forgive her for being so cruel. No, she was sick, I say over and

over, this is an illness, we need to treat it, we need to take it seriously.

But there's still that lingering thing in society that says mentally ill people

are crazy and evil, and they're not. That's a pet peeve. That's something that

surprised me. Is it the fault of my writing? I hope not; my hope is that people

will see my mother and people who suffer from mental illness in a more

compassionate way, and see people who live on the street more compassionately.

I hope that at the heart of this book lies compassion, and that readers can

find that in themselves. But you can't control how people read.  Mira Bartók is a Chicago-born artist

and writer and the author of 28 books for children. Her writing has appeared in

several literary journals and anthologies and has been noted in The Best American Essays series. She lives in western Massachusetts

where she runs

Mira Bartók is a Chicago-born artist

and writer and the author of 28 books for children. Her writing has appeared in

several literary journals and anthologies and has been noted in The Best American Essays series. She lives in western Massachusetts

where she runs  "I play piano, fiddle, baroque double harp

and a small Celtic/medieval harp. I never pursued music personally--I always

had a hard time playing in front of people unless I was in an orchestra or

singing in a large choir. And it has been the hardest thing to return to

cognitively. It is my next thing to overcome as soon as I have a little more

time (if I have a little more time!)

when things settle down after my book has been out for a while.

"I play piano, fiddle, baroque double harp

and a small Celtic/medieval harp. I never pursued music personally--I always

had a hard time playing in front of people unless I was in an orchestra or

singing in a large choir. And it has been the hardest thing to return to

cognitively. It is my next thing to overcome as soon as I have a little more

time (if I have a little more time!)

when things settle down after my book has been out for a while. Mira Bartók's compelling memoir opens with this epigraph: "Child, knowledge is a treasury and your heart its strongbox." Bartók has gathered knowledge her entire life, and kept it in her heart as talisman and anchor; in The Memory Palace, she opens her heart and shares the story of her schizophrenic mother, Norma, and what she and her sister, Natalia, had to do to survive life with, and without, a severely sick woman.

Mira Bartók's compelling memoir opens with this epigraph: "Child, knowledge is a treasury and your heart its strongbox." Bartók has gathered knowledge her entire life, and kept it in her heart as talisman and anchor; in The Memory Palace, she opens her heart and shares the story of her schizophrenic mother, Norma, and what she and her sister, Natalia, had to do to survive life with, and without, a severely sick woman.

Her sister, Natalia, joins her in Cleveland, where, for one last time, for Norma, they'd be Myra and Rachel. There, they find her storage locker, and unlock the door to the past decades--furniture, trash, cans of soup, a butcher knife. Natalia wonders if that was the one Norma had when the police caught her at Logan Airport. "I'm sure she was on her way to find me." Newspaper articles, children's books, 13 pairs of scissors (Norma had tried to slit her wrists with cutting shears after her divorce), stacks of drawings and a huge box of notebooks devoted to her eclectic research: geometry, poetry, chemistry, the Bible, medicine, botany, fairy tales. For each subject she made vocabulary lists, something Mira would have done before her brain injury. "Her files could have been my files; her notes, mine."

Her sister, Natalia, joins her in Cleveland, where, for one last time, for Norma, they'd be Myra and Rachel. There, they find her storage locker, and unlock the door to the past decades--furniture, trash, cans of soup, a butcher knife. Natalia wonders if that was the one Norma had when the police caught her at Logan Airport. "I'm sure she was on her way to find me." Newspaper articles, children's books, 13 pairs of scissors (Norma had tried to slit her wrists with cutting shears after her divorce), stacks of drawings and a huge box of notebooks devoted to her eclectic research: geometry, poetry, chemistry, the Bible, medicine, botany, fairy tales. For each subject she made vocabulary lists, something Mira would have done before her brain injury. "Her files could have been my files; her notes, mine." As Mira remembers her life, she asks, "Who am I, then, if my memory is impaired?" Old memories feel trapped in amber, and yet the part of her brain that stores museum artifacts--fossils, masks, bones--and everything else she loves to look at and draw is, for the most part, intact. If she can find the right pictures, perhaps they will lead her to the core. Memory is associative. Her mother built a memory cabinet at the storage unit; could Mira build one too? A memory palace? She starts with a photo, a close-up of her mother taken in 1959. Her face looks soft in the photograph. What can't be told from the picture is that Norma tried to fly out a second-floor wind soon after it was taken. The next picture, which Mira "hangs" across from Norma, is of Caravaggio's Medusa. Myra is in her bedroom one day when she hears a low guttural sound, followed by strange chattering and laughter. She follows the sound and sees her mother, stumbling in her underwear, spinning around with a knife in her hand, obscenities rolling off her tongue. "My sweet beautiful mother merges with Medusa."

As Mira remembers her life, she asks, "Who am I, then, if my memory is impaired?" Old memories feel trapped in amber, and yet the part of her brain that stores museum artifacts--fossils, masks, bones--and everything else she loves to look at and draw is, for the most part, intact. If she can find the right pictures, perhaps they will lead her to the core. Memory is associative. Her mother built a memory cabinet at the storage unit; could Mira build one too? A memory palace? She starts with a photo, a close-up of her mother taken in 1959. Her face looks soft in the photograph. What can't be told from the picture is that Norma tried to fly out a second-floor wind soon after it was taken. The next picture, which Mira "hangs" across from Norma, is of Caravaggio's Medusa. Myra is in her bedroom one day when she hears a low guttural sound, followed by strange chattering and laughter. She follows the sound and sees her mother, stumbling in her underwear, spinning around with a knife in her hand, obscenities rolling off her tongue. "My sweet beautiful mother merges with Medusa." Their mother's change from neglect to unremitting intrusion was gradual, and seemed to begin when Rachel started fussing with her hair and flirting with boys at school. In public she shouted out questions: "Who are you sleeping with? Are you menstruating yet? Is that sperm on your leg? Pull up your skirt and let me see." Or she would ride a bicycle to the girls' school, circle the grounds, ring the bike bell, and call their names over and over. "Where are my children? Someone has kidnapped my children!" Is that when Rachel and Myra started heaving the dresser against the bedroom door at night?

Their mother's change from neglect to unremitting intrusion was gradual, and seemed to begin when Rachel started fussing with her hair and flirting with boys at school. In public she shouted out questions: "Who are you sleeping with? Are you menstruating yet? Is that sperm on your leg? Pull up your skirt and let me see." Or she would ride a bicycle to the girls' school, circle the grounds, ring the bike bell, and call their names over and over. "Where are my children? Someone has kidnapped my children!" Is that when Rachel and Myra started heaving the dresser against the bedroom door at night?  Later that year, Myra moved to Italy. "Without my sister and family around to remind me that she is the writer and I am the artist, I start writing stories and poems. I don't want to be the person who gasps in fear whenever she hears the sound of a doorbell or a phone. I just want to lose myself in these hills, in the river winding west to the city of bridges." When she goes back to Chicago, she changes her name to Mira Bartók after signing a contract for a children's book series and realizing her mother could track her that way. She was as safe as she could be, and yet, safety still eluded her, from her time in Israel when a soldier stalked her to her life with her first husband, who was a moody, manipulative poet. She longed to be far away, in a place no one knew, and dreams, "Someday I will live in a quiet green place, off a winding country road. My house will be small but warm, and the rooms awash with light. The floor will be terra-cotta red.... Outside, I will have a small, enclosed garden, dense with vegetables and flowers.... And if I look out the window at just the right moment, the garden will be illuminated in the golding hour of the day."

Later that year, Myra moved to Italy. "Without my sister and family around to remind me that she is the writer and I am the artist, I start writing stories and poems. I don't want to be the person who gasps in fear whenever she hears the sound of a doorbell or a phone. I just want to lose myself in these hills, in the river winding west to the city of bridges." When she goes back to Chicago, she changes her name to Mira Bartók after signing a contract for a children's book series and realizing her mother could track her that way. She was as safe as she could be, and yet, safety still eluded her, from her time in Israel when a soldier stalked her to her life with her first husband, who was a moody, manipulative poet. She longed to be far away, in a place no one knew, and dreams, "Someday I will live in a quiet green place, off a winding country road. My house will be small but warm, and the rooms awash with light. The floor will be terra-cotta red.... Outside, I will have a small, enclosed garden, dense with vegetables and flowers.... And if I look out the window at just the right moment, the garden will be illuminated in the golding hour of the day."