Jonathan Evison's epic novel, West of Here, is an expansive, swaggering, utterly engrossing saga spanning a century, with dreams of exploration and growth clashing with indigenous people and lofty ideals. It's the American experience, where the past creates the present and unintended consequences of nation-building. And it's a heck of a ride.

Jonathan Evison's epic novel, West of Here, is an expansive, swaggering, utterly engrossing saga spanning a century, with dreams of exploration and growth clashing with indigenous people and lofty ideals. It's the American experience, where the past creates the present and unintended consequences of nation-building. And it's a heck of a ride.

The story begins with an end: the Elwha Dam in Port Bonita, Washington, constructed 100 years ago, is about the be torn down--the largest dam removal project ever carried out in the United States, in an effort to reclaim a major river system and salmon runs that once numbered more than 400,000 and dwindled to fewer than 4,000. The editor of the 1890's Port Bonita newspaper asked, "How do you get the public to conserve what they cannot even see the end of?" In 2006, a conservationist says, "For five generations, Port Bonita was an orgy of consumption that seemed like it would never end. Every day was Dam Day. But now it was time to clean up the mess."

At the annual Dam Days celebration in September 2006, Dave Krigstadt ("Krig") listens to his boss, Jared Thornburgh, give a speech to a swiftly disappearing crowd of Port Bonitans as "the rain came hissing up the little valley in sheets." Jared flees the rain, too, after he says "There is a future.... And it begins right now." Krig, the only one remaining, walks over to the fence above the Elwha Dam, watching the water roar into the canyon as fall Chinook beat their silver heads over and over against the concrete. As a kid, he thought it was funny. He muses about the dam, the  salmon, the future and his past, as he works his high school basketball championship ring off his finger. Twenty-two years have passed, and playing on that winning Bucket Brigade team is still the high point of his life. But one has to start somewhere, so he tosses the ring into the chasm.

salmon, the future and his past, as he works his high school basketball championship ring off his finger. Twenty-two years have passed, and playing on that winning Bucket Brigade team is still the high point of his life. But one has to start somewhere, so he tosses the ring into the chasm.

Jump back to January 1880: a gale-force storm roars inland, dropping more than four feet of snow near the mouth of the Elwha River. "It is said among the Klallam that the world disappeared the night of the storm, and that the river turned to snow, and the forest and mountains and sky turned to snow. It is said that the wind itself turned to snow as it thundered up the valley and that the trees shivered and the valley moaned. At dusk, in a cedar shack near the mouth of the river, a boy child was born...." For six months the boy child had no name, until his mother decided on Thomas Jefferson King. But he was given another name by Indian George, a Klallam elder; upon meeting the blue-eyed, mute child, he called him Storm King.

Between these two events lie the establishment of a utopian community, the building of the dam, the ambitions of entrepreneurs, the education of a would-be newspaperwoman and a prostitute, and, ultimately, the decline of a city with promise--Port Bonita, whose backers thought it would be the jewel of the newest state, outdoing Seattle for the honor, since the Great Fire of 1889 had reduced the rival city to rubble.

Between these two events lie the establishment of a utopian community, the building of the dam, the ambitions of entrepreneurs, the education of a would-be newspaperwoman and a prostitute, and, ultimately, the decline of a city with promise--Port Bonita, whose backers thought it would be the jewel of the newest state, outdoing Seattle for the honor, since the Great Fire of 1889 had reduced the rival city to rubble.

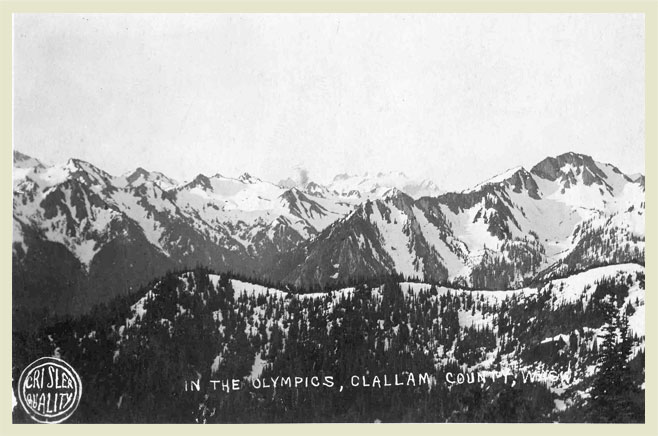

Woven through the stories of past and present is the expedition of James Mather, who was given the task of exploring the uncharted interior of the Olympic Peninsula between the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the coast of the Pacific. Viewed from the Strait, "The high country was marked by gaps so steep and dark that the eye could scarcely penetrate them. And all of this was wrapped tightly about the waist with an impenetrable green blanket of timber." Viewed from Elliott Bay to the south, the Olympic Mountains presented a sheer wall of basalt, so steep in places that snow wouldn't stick. Mather chose, surprisingly, to set out on his 1889 expedition in the dead of one of the worst winters on record, because he was determined to be the first to penetrate the wilderness.

Port Bonita in 1889 was a rough, ragged town, with a ramshackle hotel, the Olympic, and a skeezy saloon, the Belvedere, run by John Tobin, a mean man and supplier of illegal whiskey to the Klallams. The men in the town "shared an appetite for new possibilities," from the obvious ones in the port to signing on with Mather to establishing a commonwealth outside of town. Women also had an appetite for new possibilities: Eva Lambert came to the commonwealth, pregnant and single, to be a newspaper reporter; Gertie McGrew came to the saloon to be a madam.

As Mather gathers information on the Elwha and points farther afield, a trapper named Lofall convinces him that the river is navigable by flatboat, but his other story seems too tall: a bear-man, howling on a riverbank like the devil himself. When Mather talks to the Klallams, they tell of a fertile valley, an idyllic paradise, yet one that the natives did not venture into, having been warned away by Thunderbird, a fire-spewing bird god.

As Mather gathers information on the Elwha and points farther afield, a trapper named Lofall convinces him that the river is navigable by flatboat, but his other story seems too tall: a bear-man, howling on a riverbank like the devil himself. When Mather talks to the Klallams, they tell of a fertile valley, an idyllic paradise, yet one that the natives did not venture into, having been warned away by Thunderbird, a fire-spewing bird god.

Shortly after Mather arrives in town, Ethan Thornburgh shows up, looking for Eva Lambert. They had left Chicago together for the Northwest but she had abandoned him in Seattle, and he has tracked her down to make an honest woman of her, to get her to put aside her ambitions and the rest of it and get serious. "The rest of what? The rest of me? The rest of my life? Why is it every time a woman gets serious, she has to set something aside?" Ethan says she doesn't have to give up anything. He looks outside and says, "It's glorious, it's endless. It's up for grabs....Why not us, Eva? You're a new woman, why not a new life?"

The feeling of limitless opportunity and riches fuels everyone in Port Bonita--unexplored territory, inexhaustible timber, salmon runs that defy description. Ethan wanders out to the foothills, passing land grab claims, and finally comes to the head of a canyon where the Elwha thunders, and decides to build a cabin there, already dreaming of the mark he will make on the river. The first night, as he sleeps on a bed of spruce boughs, he's awakened by a howl, then a series of whoops and answering calls from the other side of the chasm--eerie, loud sounds, not owls, not elk. Perhaps the trapper and the Klallams weren't in thrall to dark imagination and myth. Perhaps there is something out there.

The characters in early Port Bonita are deftly drawn, and one of the many pleasures in West of Here is seeing how their personalities are carried over in their descendants. James Mather is an inveterate explorer, running out of virgin wilderness. But he wonders, what is the purpose of exploration but escape? Is he cowardice dressed up in snowshoes? Isn't Ethan throwing himself into the unknown just as bravely as Mather, but without the self-doubt? Indian George Sampson is a Klallam with a command of the King's English, a distaste for salmon and a fondness for sourdough bread. Dalton Krigstadt only hauls things, but comes up with an idea to harvest ice. Hoko, Thomas's mother, changes from an innocent girl to a bitter woman after the birth of her son--a mute and dreamy boy, following the sounds in his head. Adam has been taking a census of the territory and everything in it, but his current mission is to find out who is selling the natives liquor. Those drives, concerns and questions continue 100 years later for a new generation.

The Mather expedition leaves with five men, two mules and two dogs, starting out in a downpour. Inauspicious, but their morale is high--the terrain is easy, the fish plentiful, and they have worlds to conquer. Even the strange wailing in the night, like the "lament of some grizzled bagpipe," fails to dampen their spirits, but soon the terrain and the weather take their toll. After three months, they do not find Eden, but still another precipitous valley, and a terrifying mountain laden with blue glaciers and cut through with crevasses, a "sculptured face glowering at heaven"--Mt. Olympus. Mather wonders about the wisdom of embarking on this journey in the spring rather than winter. "But spring was too late. Destiny could not wait until spring."

The Mather expedition leaves with five men, two mules and two dogs, starting out in a downpour. Inauspicious, but their morale is high--the terrain is easy, the fish plentiful, and they have worlds to conquer. Even the strange wailing in the night, like the "lament of some grizzled bagpipe," fails to dampen their spirits, but soon the terrain and the weather take their toll. After three months, they do not find Eden, but still another precipitous valley, and a terrifying mountain laden with blue glaciers and cut through with crevasses, a "sculptured face glowering at heaven"--Mt. Olympus. Mather wonders about the wisdom of embarking on this journey in the spring rather than winter. "But spring was too late. Destiny could not wait until spring."

In present-day Port Bonita, the weather is much the same, and the once-promising town is, according to Curtis, a teenage Klallam, "one big f***ing Wal-Mart." He meets with his guidance counselor about a job shadowing a tribal elder, but he balks. "Why couldn't his people just adapt? And what were they trying to sell him, anyway?... He knew being a Klallam back in the day wasn't all communing with nature and dancing with spirits. He knew about the slave trade.... He knew about the violence and hatred the Klallam had visited on the Tsimshians as well as the whites.... Funny, you never heard the elders singing that tune." But Curtis may be tied to his heritage more than he realizes; like Thomas, the Storm King, he wanders and has unsettling dreams.

In present-day Port Bonita, the weather is much the same, and the once-promising town is, according to Curtis, a teenage Klallam, "one big f***ing Wal-Mart." He meets with his guidance counselor about a job shadowing a tribal elder, but he balks. "Why couldn't his people just adapt? And what were they trying to sell him, anyway?... He knew being a Klallam back in the day wasn't all communing with nature and dancing with spirits. He knew about the slave trade.... He knew about the violence and hatred the Klallam had visited on the Tsimshians as well as the whites.... Funny, you never heard the elders singing that tune." But Curtis may be tied to his heritage more than he realizes; like Thomas, the Storm King, he wanders and has unsettling dreams.

So he goes with a shadow job at High Tide, the only seafood processor left in town. He reports to Krig, the production manager, who chafes at working for Jared, a state senator's son. "Where the hell was Thornburgh when Krig led the Bucket Brigade to the regional championship on the glory of his sweet stroke and sure-handed crossover, huh?... Who was pulling honor roll two years in a row? That's right, Krig. Not as dumb as he looked." Krig is in a dead end job and knows it; Jared shares his frustration: "How had his life been reduced to such trivialities?... Thornburghs didn't ponder the shipping cost of canned clams... [they] built dams out of mountains and put towns on maps!" At least Krig has a mission: he's a Sasquatch spotter, although he has only heard noises, not actually seen anything. He goes up the Elwha at night, armed with Sasquatch calls and a softball bat for making syncopated knocks on trees.

The characters in present-day Port Bonita are just as intriguing as the early settlers. Timmon Tillman is an ex-con who ends up there looking for a fresh start and just wants to be left alone. In search of solitude, he sets off into the wilderness with a modest store of food and five stolen library books. Franklin Bell is Tillman's parole officer, the only black man for miles. Bell hums Don Henley tunes, gives pep talks and drinks eggnog ("I know what you're thinkin'... what kinda dude drinks eggnog in June? Well, now, you take one look out that window and you tell me it looks like June, Tillman. Looks like goddamn Christmas to me.") Rita, Curtis's mom, has a dreary job gutting fish at High Tide. Hillary Burch works for Fish and Wildlife doing environmental impact studies, trying to predict how the landscape will react once the dam is removed; like Eva Lambert, she wants to make her way in the world unencumbered by society's expectations. Meriwether Lewis Charles, an elderly Klallam (and a sharp dresser), dispenses wisdom and caustic remarks with equal skill, and senses that Curtis "walks between worlds."

Jonathan Evison also walks between worlds in this sprawling, splendid novel. His sense of place is impeccable, as he limns a landscape of always-waning light, gray skies, snow and howling winds, driving rain, steady rain, drizzling rain and the omnipresent river, "a flashing silver serpent as it roared down the mountains." He captures the awesomeness and the beauty of the wilderness, coupled with man's desire to conquer it in a restless quest for adventure and riches.

Jonathan Evison also walks between worlds in this sprawling, splendid novel. His sense of place is impeccable, as he limns a landscape of always-waning light, gray skies, snow and howling winds, driving rain, steady rain, drizzling rain and the omnipresent river, "a flashing silver serpent as it roared down the mountains." He captures the awesomeness and the beauty of the wilderness, coupled with man's desire to conquer it in a restless quest for adventure and riches.

At the same time that Evison is entertaining us with story and character, he also draws attention to thorny contemporary issues--habitat degradation, Native American alcoholism, dying small towns. Credit Evison's rich imagination for being able to combine the serious and the zany seamlessly in his storytelling, for bringing the Sasquatch into the same story in which Lord Jim, a Klallam elder, with his dying words, counsels us, "We are born haunted. Haunted by our fathers and mothers and daughters, and by people we don't remember. We are haunted by otherness, by the oath not taken, by the life unlived. We are haunted by the changing winds and the ebbing tides of history. And even as our own flame burns brightest, we are haunted by the embers of the first dying fire. But mostly, we are haunted by ourselves."--Marilyn Dahl

Fiction writers toil

alone for years before a note from a complete stranger shows

he/she gets what you're trying to do and is crazy in love with it. Can you

recall a moment when that happened for you?

Fiction writers toil

alone for years before a note from a complete stranger shows

he/she gets what you're trying to do and is crazy in love with it. Can you

recall a moment when that happened for you? Clams.

No, really! Actually, I wanted to write a history of the Olympic Peninsula, a

place near and dear to me. I spend an awful lot of time hiking and camping in

the Olympics, making frequent stops in Sequim, and Port Angeles, and Forks. I

live for these getaways. My old Dodge motor home allows me to basically live on

the road. While researching in earnest, I was conceiving something along lines

of a historical novel, but I soon realized that what I really wanted to write

was a novel about history, about the countless tiny connections that bind

people together, and tie people to a place, and a time, and how the sum total

of all these connections amounted to a living breathing history. I wanted to

bring the place to life on the page, like Steinbeck brought central California

to life, or Twain brought the Mississippi to life.

Clams.

No, really! Actually, I wanted to write a history of the Olympic Peninsula, a

place near and dear to me. I spend an awful lot of time hiking and camping in

the Olympics, making frequent stops in Sequim, and Port Angeles, and Forks. I

live for these getaways. My old Dodge motor home allows me to basically live on

the road. While researching in earnest, I was conceiving something along lines

of a historical novel, but I soon realized that what I really wanted to write

was a novel about history, about the countless tiny connections that bind

people together, and tie people to a place, and a time, and how the sum total

of all these connections amounted to a living breathing history. I wanted to

bring the place to life on the page, like Steinbeck brought central California

to life, or Twain brought the Mississippi to life.  Did you develop a

method for keeping track of such a huge cast of characters living in two

very different time periods?

Did you develop a

method for keeping track of such a huge cast of characters living in two

very different time periods? Chuck

Adams is executive editor of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. In a publishing

career that reaches back 40 years, he has acquired and edited hundreds of

fiction and nonfiction titles from authors as diverse as Sandra Brown, James Lee Burke, Mary Higgins Clark and Ronald Reagan. Since coming to

Algonquin Books in 2004 he has continued to advocate for books that feature

vivid storytelling that will entrance readers, with one prime example being Water

for Elephants by Sara Gruen (Algonquin,

2006).

Chuck

Adams is executive editor of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. In a publishing

career that reaches back 40 years, he has acquired and edited hundreds of

fiction and nonfiction titles from authors as diverse as Sandra Brown, James Lee Burke, Mary Higgins Clark and Ronald Reagan. Since coming to

Algonquin Books in 2004 he has continued to advocate for books that feature

vivid storytelling that will entrance readers, with one prime example being Water

for Elephants by Sara Gruen (Algonquin,

2006).

Novelist and editor

Novelist and editor  Book that changed your life:

Book that changed your life:  salmon, the future and his past, as he works his high school basketball championship ring off his finger. Twenty-two years have passed, and playing on that winning Bucket Brigade team is still the high point of his life. But one has to start somewhere, so he tosses the ring into the chasm.

salmon, the future and his past, as he works his high school basketball championship ring off his finger. Twenty-two years have passed, and playing on that winning Bucket Brigade team is still the high point of his life. But one has to start somewhere, so he tosses the ring into the chasm. Between these two events lie the establishment of a utopian community, the building of the dam, the ambitions of entrepreneurs, the education of a would-be newspaperwoman and a prostitute, and, ultimately, the decline of a city with promise--Port Bonita, whose backers thought it would be the jewel of the newest state, outdoing Seattle for the honor, since the Great Fire of 1889 had reduced the rival city to rubble.

Between these two events lie the establishment of a utopian community, the building of the dam, the ambitions of entrepreneurs, the education of a would-be newspaperwoman and a prostitute, and, ultimately, the decline of a city with promise--Port Bonita, whose backers thought it would be the jewel of the newest state, outdoing Seattle for the honor, since the Great Fire of 1889 had reduced the rival city to rubble. As Mather gathers information on the Elwha and points farther afield, a trapper named Lofall convinces him that the river is navigable by flatboat, but his other story seems too tall: a bear-man, howling on a riverbank like the devil himself. When Mather talks to the Klallams, they tell of a fertile valley, an idyllic paradise, yet one that the natives did not venture into, having been warned away by Thunderbird, a fire-spewing bird god.

As Mather gathers information on the Elwha and points farther afield, a trapper named Lofall convinces him that the river is navigable by flatboat, but his other story seems too tall: a bear-man, howling on a riverbank like the devil himself. When Mather talks to the Klallams, they tell of a fertile valley, an idyllic paradise, yet one that the natives did not venture into, having been warned away by Thunderbird, a fire-spewing bird god.  The Mather expedition leaves with five men, two mules and two dogs, starting out in a downpour. Inauspicious, but their morale is high--the terrain is easy, the fish plentiful, and they have worlds to conquer. Even the strange wailing in the night, like the "lament of some grizzled bagpipe," fails to dampen their spirits, but soon the terrain and the weather take their toll. After three months, they do not find Eden, but still another precipitous valley, and a terrifying mountain laden with blue glaciers and cut through with crevasses, a "sculptured face glowering at heaven"--Mt. Olympus. Mather wonders about the wisdom of embarking on this journey in the spring rather than winter. "But spring was too late. Destiny could not wait until spring."

The Mather expedition leaves with five men, two mules and two dogs, starting out in a downpour. Inauspicious, but their morale is high--the terrain is easy, the fish plentiful, and they have worlds to conquer. Even the strange wailing in the night, like the "lament of some grizzled bagpipe," fails to dampen their spirits, but soon the terrain and the weather take their toll. After three months, they do not find Eden, but still another precipitous valley, and a terrifying mountain laden with blue glaciers and cut through with crevasses, a "sculptured face glowering at heaven"--Mt. Olympus. Mather wonders about the wisdom of embarking on this journey in the spring rather than winter. "But spring was too late. Destiny could not wait until spring."  In present-day Port Bonita, the weather is much the same, and the once-promising town is, according to Curtis, a teenage Klallam, "one big f***ing Wal-Mart." He meets with his guidance counselor about a job shadowing a tribal elder, but he balks. "Why couldn't his people just adapt? And what were they trying to sell him, anyway?... He knew being a Klallam back in the day wasn't all communing with nature and dancing with spirits. He knew about the slave trade.... He knew about the violence and hatred the Klallam had visited on the Tsimshians as well as the whites.... Funny, you never heard the elders singing that tune." But Curtis may be tied to his heritage more than he realizes; like Thomas, the Storm King, he wanders and has unsettling dreams.

In present-day Port Bonita, the weather is much the same, and the once-promising town is, according to Curtis, a teenage Klallam, "one big f***ing Wal-Mart." He meets with his guidance counselor about a job shadowing a tribal elder, but he balks. "Why couldn't his people just adapt? And what were they trying to sell him, anyway?... He knew being a Klallam back in the day wasn't all communing with nature and dancing with spirits. He knew about the slave trade.... He knew about the violence and hatred the Klallam had visited on the Tsimshians as well as the whites.... Funny, you never heard the elders singing that tune." But Curtis may be tied to his heritage more than he realizes; like Thomas, the Storm King, he wanders and has unsettling dreams. Jonathan Evison also walks between worlds in this sprawling, splendid novel. His sense of place is impeccable, as he limns a landscape of always-waning light, gray skies, snow and howling winds, driving rain, steady rain, drizzling rain and the omnipresent river, "a flashing silver serpent as it roared down the mountains." He captures the awesomeness and the beauty of the wilderness, coupled with man's desire to conquer it in a restless quest for adventure and riches.

Jonathan Evison also walks between worlds in this sprawling, splendid novel. His sense of place is impeccable, as he limns a landscape of always-waning light, gray skies, snow and howling winds, driving rain, steady rain, drizzling rain and the omnipresent river, "a flashing silver serpent as it roared down the mountains." He captures the awesomeness and the beauty of the wilderness, coupled with man's desire to conquer it in a restless quest for adventure and riches.