The first round of keynote presentations at Tools of Change

culminated Tuesday morning with Margaret Atwood, who noted the energetic discussion about advances in e-book technology--some already come to fruition, some still on the

horizon--but cautioned her audience, "Forgive me for not being as hyped up

about it all as some people  might be." She concerned herself with the

economic consequences of changes in publishing for the authors, the "primary

source" upon which the entire industry depends, and argued against the

notion that books should be free, or close to it, with authors making up the

lost revenue through ancillary efforts. "Rock concerts and T-shirts are

not an option," she insisted, later putting the question in stark terms: "Do

you want lots of people reading your book or do you want a cheese sandwich?"

might be." She concerned herself with the

economic consequences of changes in publishing for the authors, the "primary

source" upon which the entire industry depends, and argued against the

notion that books should be free, or close to it, with authors making up the

lost revenue through ancillary efforts. "Rock concerts and T-shirts are

not an option," she insisted, later putting the question in stark terms: "Do

you want lots of people reading your book or do you want a cheese sandwich?"

On Wednesday morning, Kevin Kelly of Wired blithely said, "I

can't really figure out what books should be more expensive than a song, and I

don't think consumers will believe that, either." Thus he predicted the

price of e-books could fall as low as 99 cents, as easy technological

reproducibility strips away the value of a work of art, forcing creators to

turn to "that which cannot be copied," such as immediacy, authentication,

personalization and embodiment. One of the slides he used to illustrate this

new economic model? A live music performance.

The tension between authors and the marketplace was one of

several economic relationships that were explored during the O'Reilly Media

conference's two days of panels and presentations (following a full day of

intensive workshops). The bonds between readers and e-book manufacturers and

publishers were explored in two Wednesday sessions. First, Kobo executive v-p Michael Tamblyn profiled four major types of e-book consumers the

company has encountered, from the "eInk reading machine," who spends

close to $200 a month primarily on new fiction releases downloaded to a

dedicated reader, to the "freegan," who reads free books exclusively,

usually accessing them on the web. Most customers have at least one free book

in their library, he observed; they might get one as an experiment, with a

smaller segment getting two free books because "they like Jane Austen,"

he quipped. After 14 freebies, users tend to max out on the number of books

they can find that they like and want to read (although "freegan hoarders"

with 100 or more titles in their libraries do exist).

Later, bloggers Sarah Wendell and Jane Litte addressed e-book

devices from the end user's perspective, arguing for devices with hardware that

conforms more fully to consumer needs (like easy one-handed access for

commuters whose other hand grasps a strap on a moving train) and software that

allows readers to manage their digital collections seamlessly. Readers don't

care about industry conflicts like the lack of electronic rights for cover art

that leaves many e-books coverless, they said; all they know is that there's

something they want that they aren't getting. And when that happens, "readers

blame the problems on the retailer and the author," Litte said, "because

that's who they have the relationship with."

At the packed panel on "Bookselling in the 21st Century,"

audience members eager for insight into how independent bookstores might

continue to thrive received a strong dose of optimism. "I don't feel like

Amazon is killing us, because we're not dead," said Jessica Stockton

Bagnulo of Greenlight Bookstore, Brooklyn, N.Y. "We compete by not competing."

Jenn Northington of WORD, also in Brooklyn, concurred, saying, "Apple,

Amazon and Google are not booksellers. Books are loss leaders for them. It's

not their livelihood." What about the Borders bankruptcy? "Nobody

knows what kind of hole that's going to leave in the industry," Stockton

Bagnulo admitted, but she hoped that it might lead to a more diverse

marketplace and called upon publishers to assist booksellers in educating

consumers, "helping them find the next place they're going to get their

books." (It wouldn't be that hard: publishers could impress the message

upon their authors, who could use their social media platforms to spread the

word to their fans.)

Often at TOC the most memorable presentations seek to redefine

what a "book" could be, and this year was no exception. Theodore Gray

of Touch Press dazzled attendees with brief snippets from the iPad apps his

company, Touch Press, had developed for The

Elements and the forthcoming Solar

System, as well as the first few minutes of a riveting performance by Fiona

Shaw for an electronic edition of T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land. Hours later,  Magellan Media's Brian O'Leary accused

the publishing industry of being "unduly governed by the containers we've

used for centuries" and clinging to "mental models that constrain our

ability to change." By focusing on the context in which information is

presented, rather than the container, he suggested, publishers could leverage

the existing abundance of content and give readers more flexible access to the

information they need when they need it--perhaps even eliminating the end-user

frustrations that lead consumers to seek that information from alternative, "pirate"

venues in the first place.

Magellan Media's Brian O'Leary accused

the publishing industry of being "unduly governed by the containers we've

used for centuries" and clinging to "mental models that constrain our

ability to change." By focusing on the context in which information is

presented, rather than the container, he suggested, publishers could leverage

the existing abundance of content and give readers more flexible access to the

information they need when they need it--perhaps even eliminating the end-user

frustrations that lead consumers to seek that information from alternative, "pirate"

venues in the first place.

As for what the first stages of such innovation would look like

in the practical world, O'Reilly and Ingram Content Group offered a hint in a

session outlining their shift toward a "continuous publishing" model

that emphasized smaller print runs (allowing for quicker updates) and increased

reliance on printing on demand (through Ingram's Lightning Source) to

drastically reduce the number of steps involved in taking a content file and

producing an item ready to be shipped to retail outlets or direct to

customers--with the money saved on production being invested in improved

content development. The ultimate goal, said O'Reilly chief operating officer

Laura Baldwin, was to make every book "always available, always relevant,

and never out of stock."

Another optimistic glimpse of the future came from the bookselling

panel, as Booktour.com's Kevin Smokler encouraged bookstore owners to learn

about their regular customers (including researching them on Facebook and

Goodreads, if possible), and anticipated a day when the Espresso Book Machine

becomes small enough and cheap enough and is stocked with a deep enough

inventory of titles to be responsive to those customers' interests. "I

look forward to the day when all my favorite bookstores have one of those

machines cooling its heels in the back room," he proposed, so that nobody

would ever have to wait on a special order ever again. Under such a scenario,

the other panelists seemed to agree, bookstores could focus on the challenges

of organizing their local literary communities and becoming genuine neighborhood

fixtures. After all, "you have to determine what's unique about your

space," Smokler advised--"and it's not the fact that you sell books."--Ron

Hogan

drown out all reasonable discourse--but they never do. That doesn't mean such people can't do serious damage--they can. But don't blame technology.... We're just beginning to discover what might come of linking the world electronically. I can't wait to see what comes next. But then, I always liked a good story."

drown out all reasonable discourse--but they never do. That doesn't mean such people can't do serious damage--they can. But don't blame technology.... We're just beginning to discover what might come of linking the world electronically. I can't wait to see what comes next. But then, I always liked a good story."

Only a day after Borders Group in the U.S. filed for chapter 11

bankruptcy reorganization, the parent company of Borders in Australia

and New Zealand, which has no connection with the American company, also

went bankrupt.

Only a day after Borders Group in the U.S. filed for chapter 11

bankruptcy reorganization, the parent company of Borders in Australia

and New Zealand, which has no connection with the American company, also

went bankrupt. In an editorial, the

In an editorial, the  What does the Borders Bankruptcy mean for Kobo e-reader owners?

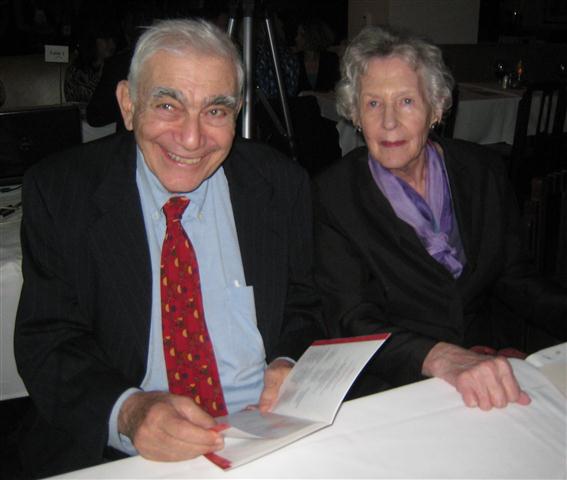

What does the Borders Bankruptcy mean for Kobo e-reader owners?  On Tuesday night, the Washington Literary

Council presented its Lifetime Literacy Achievement award, honoring "those

who consistently advocate for literacy, support reading for the entire

community, and provide opportunities for readers of all ages to gather, to

explore, and to learn," to Politics & Prose co-owners Barbara Meade

and the late Carla Cohen. Carla's husband, David Cohen, accepted on her behalf.

On Tuesday night, the Washington Literary

Council presented its Lifetime Literacy Achievement award, honoring "those

who consistently advocate for literacy, support reading for the entire

community, and provide opportunities for readers of all ages to gather, to

explore, and to learn," to Politics & Prose co-owners Barbara Meade

and the late Carla Cohen. Carla's husband, David Cohen, accepted on her behalf.

Special Occasions bookstore, Winston-Salem, N.C., will close "sometime after Mother's Day" as owners Ed and Miriam McCarter yield "to a weak economy and strong competition from e-books and online booksellers," the

Special Occasions bookstore, Winston-Salem, N.C., will close "sometime after Mother's Day" as owners Ed and Miriam McCarter yield "to a weak economy and strong competition from e-books and online booksellers," the  What does the news that Borders has declared bankruptcy and will be closing a third of its stores mean for independent booksellers? Reaction and analysis were immediate once the story broke.

What does the news that Borders has declared bankruptcy and will be closing a third of its stores mean for independent booksellers? Reaction and analysis were immediate once the story broke. In a

In a  Gayle Shanks, owner of

Gayle Shanks, owner of

In New Orleans, two Borders stores will close. Britton Trice, owner of the

In New Orleans, two Borders stores will close. Britton Trice, owner of the

In Normal, Ill., where a Borders will close, Sarah Lindenbaum, manager of Babbitt's Books, said, "I'm a little bit wary, because it's never good when books fall by the wayside in any form at all." Although her store does not stock new books, she expressed some concern "because Borders customers later help re-supply Babbitt's 'bread and butter' section, trade paperback fiction, with 'new' used titles," the

In Normal, Ill., where a Borders will close, Sarah Lindenbaum, manager of Babbitt's Books, said, "I'm a little bit wary, because it's never good when books fall by the wayside in any form at all." Although her store does not stock new books, she expressed some concern "because Borders customers later help re-supply Babbitt's 'bread and butter' section, trade paperback fiction, with 'new' used titles," the  might be." She concerned herself with the

economic consequences of changes in publishing for the authors, the "primary

source" upon which the entire industry depends, and argued against the

notion that books should be free, or close to it, with authors making up the

lost revenue through ancillary efforts. "Rock concerts and T-shirts are

not an option," she insisted, later putting the question in stark terms: "Do

you want lots of people reading your book or do you want a cheese sandwich?"

might be." She concerned herself with the

economic consequences of changes in publishing for the authors, the "primary

source" upon which the entire industry depends, and argued against the

notion that books should be free, or close to it, with authors making up the

lost revenue through ancillary efforts. "Rock concerts and T-shirts are

not an option," she insisted, later putting the question in stark terms: "Do

you want lots of people reading your book or do you want a cheese sandwich?" Magellan Media's Brian O'Leary accused

the publishing industry of being "unduly governed by the containers we've

used for centuries" and clinging to "mental models that constrain our

ability to change." By focusing on the context in which information is

presented, rather than the container, he suggested, publishers could leverage

the existing abundance of content and give readers more flexible access to the

information they need when they need it--perhaps even eliminating the end-user

frustrations that lead consumers to seek that information from alternative, "pirate"

venues in the first place.

Magellan Media's Brian O'Leary accused

the publishing industry of being "unduly governed by the containers we've

used for centuries" and clinging to "mental models that constrain our

ability to change." By focusing on the context in which information is

presented, rather than the container, he suggested, publishers could leverage

the existing abundance of content and give readers more flexible access to the

information they need when they need it--perhaps even eliminating the end-user

frustrations that lead consumers to seek that information from alternative, "pirate"

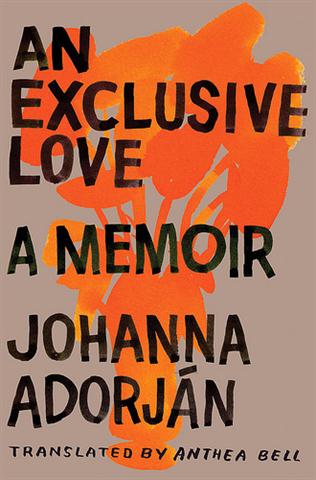

venues in the first place. The book tells the story of Adorján's grandparents, who committed suicide together, focusing on their last day alive. In part, GBO described the book this way: "Sixteen years after her grandparents' death, Johanna Adorján sets out to fill the gaps of their story, in the process discovering unexpected things about herself and her family. Against the backdrop of the horrors of the 20th-century, she brings Vera and István back to life--a fascinating couple, peculiarly stylish, stubborn, and eccentric. With an extraordinary blend of true reporting and novelistic recreation Johanna Adorján tries to understand their last and powerful act.

The book tells the story of Adorján's grandparents, who committed suicide together, focusing on their last day alive. In part, GBO described the book this way: "Sixteen years after her grandparents' death, Johanna Adorján sets out to fill the gaps of their story, in the process discovering unexpected things about herself and her family. Against the backdrop of the horrors of the 20th-century, she brings Vera and István back to life--a fascinating couple, peculiarly stylish, stubborn, and eccentric. With an extraordinary blend of true reporting and novelistic recreation Johanna Adorján tries to understand their last and powerful act.  Julia DeSmit has appeared in two previous novels by Baart: After the Leaves Fall and Summer Snow. Julia is now 24, a single mom of five-year-old Daniel and loving big sister to 10-year-old Simon. These three live with a very saintly grandmother who encourages, cajoles and prods in the nicest way and reminds all of them of their dependence upon each other and God.

Julia DeSmit has appeared in two previous novels by Baart: After the Leaves Fall and Summer Snow. Julia is now 24, a single mom of five-year-old Daniel and loving big sister to 10-year-old Simon. These three live with a very saintly grandmother who encourages, cajoles and prods in the nicest way and reminds all of them of their dependence upon each other and God.