Your protagonist, Jacob Marlowe, is a werewolf hunted by agents determined to end his 200-year-old life ("I was in Europe when Nietzsche and Darwin between them got rid of God"). What inspired you to combine Marlowe's efforts to foil repeated assaults with your own meditations on the themes of sex, death and transformation?

Your protagonist, Jacob Marlowe, is a werewolf hunted by agents determined to end his 200-year-old life ("I was in Europe when Nietzsche and Darwin between them got rid of God"). What inspired you to combine Marlowe's efforts to foil repeated assaults with your own meditations on the themes of sex, death and transformation?

For me these themes--along with love and loss, compassion and cruelty--are unavoidable perennials. They're necessary, in the philosophical sense. After my previous book, A Day and a Night and a Day, had fared exactly as its six predecessors (that is, it was critically more or less well-received but virtually no one bought it), I had a conversation with my agent in which he assured me that if I wrote another overtly literary novel he wouldn't be able to sell it. So I decided to write a straight commercial genre novel. No philosophy, no existential angst, no abstract ideas, no metafictional conceits. Just a ripping yarn. Just a page turner. How difficult could that be, with a werewolf for a protagonist?

Rewardingly difficult, it turned out. As soon as I began, it was obvious Jake's conflicts and dilemmas were human, all too human. Like it or not, it was thematic business as usual. So it's not inspiration. It's just that whatever I set out to write about, what I end up writing about is love, sex, death, etc.

The name Jacob Marlowe carries multiple resonances. How did you select the name for your main character?

The Marlowe allusions I had consciously in mind were to Chandler, Conrad and Christopher Marlowe, all for obvious reasons. It was "Jake Marlowe" from the book's inception; there were no other contenders. Sometimes it's like that: a character arrives with traits or facts attached that don't admit alteration. (It was only later someone told me there was another werewolf doing the rounds with the same first name...) In any case, fictional nomenclature's never arbitrary, at least not with the major characters. Even names one appears to choose casually, without any ulterior symbolic, allusive or even phonetic motives, subsequently reveal (often via third-party critical analysis) the subconscious quietly following its own agenda. As Mailer said, it's a spooky art.

How did you go about constructing an evolving personality for an almost-200-year-old being who, to the outer world, appears ageless and not out of the ordinary, but is in fact very, very different from you and me?

At the risk of sounding irascible: What do you mean, 'How did you go about constructing an evolving personality...'? That's what novelists do. You sit down with a character and imagine how he or she would respond to a given situation. The given situation here is (a) turning into a homicidal monster once a month and (b) having an expected lifespan of 400 years, but the imaginative process is exactly the same as it would be if the given situation happened to be a 50-year-old midwest housewife discovering her husband's having an affair with his secretary. You use your imagination. And at the further risk of opprobrium (and police investigation), I confess I don't think Marlowe is all that different from 'you and me.' If he was, we wouldn't sympathize with him or get his jokes. Granted, lycanthropy forces him to kill and eat people, but the point is, lycanthropy would force 'you and me' to do exactly the same. The whole novel depends on seeing ourselves in the monster and the monster in ourselves.

Marlowe has traveled widely and seen much over his 200 years. He is also blessed with a remarkable memory, an ironic sense of humor and a vulpine sexuality undiminished by time. You've worked much history and philosophy into the novel, but were there scenes and sidetrips/excursions that you found you had to leave out?

Yes. I gravitate to the ruminative, the abstract, the digressive. I prefer ideas to action and I'm not a natural dramatist. Fortunately, editors murder reflective asides for a living.

Throughout The Last Werewolf you sprinkle allusions to literature and pop culture. Graham Greene, Vladimir Nabokov, D.H. Lawrence, Bret Easton Ellis, Starsky and Hutch and Apocalypse Now make brief, often very funny cameos. What is the secret for allowing you the opportunity to drop in these lovely bits of homage while never slowing the pace?

The secret is... get it right. The secret is judgment. With the exception of the spooky or subconscious element conceded above, that's always the secret. It's not an exciting secret. It's not even a secret. Writing well means exercising judgment at every level, from theme to phoneme. And unless you're Shakespeare there's no short-cut to that. You just have to spend a lot of time doing it and learning from your mistakes. If The Last Werewolf has the right amount of cultural references--enough to amuse but not to annoy--I'm delighted. But as far as the secret recipe for the right amount goes... it doesn't exist.

After university you were a bookseller. What insights about the reading public or the health of particular literary genres did you gain from that experience?

I don't know if the distinction's valid in the U.S., but in the U.K., you need to differentiate between corporate and independent bookselling. I've done both. British corporate bookselling is (or was, when I was an employee) soul-destroying. The company I was with in the early '90s might as well have been Burger King for all the interest it had in books. I loathed life behind the corporate counter, from the scripted phone responses to the risible uniforms. The only comfort was like-minded colleagues, with whom I spent lunch hours fantasizing about doing violence to rude customers or plotting how to rob the shop safe. On the other hand, my years at Chapter & Verse (independent, now no longer a going concern) were happy ones. Small, labyrinthine shop, eclectic stock, laidback manager, fiercely loyal clientele, wear what you like, food and drink allowed on the shop floor--most astonishingly, feel free to read at the till. Bliss!

The only thing I learned about the reading public was that the majority had lousy taste in books. I didn't actually learn that as a bookseller, I knew it anyway, but it's one thing to know it in the abstract, it's quite another to be seeing it--to be handling it--on a daily basis. On the up side, incessantly ringing up sales for bad writers was the perfect goad. I went home in the evenings and wrote.

---

You can view a trailer for Glen Duncan's The Last Werewolf here.

As this remarkable novel comes out, many will be the reviewers and readers who note that one of its themes is how a person comes to terms with who he or she is. That's because, of course, protagonist Jacob Marlowe is a werewolf.

As this remarkable novel comes out, many will be the reviewers and readers who note that one of its themes is how a person comes to terms with who he or she is. That's because, of course, protagonist Jacob Marlowe is a werewolf. Along with the naughty bits we also get plenty of literary allusions, including everything from Marlowe's name itself to Shakespeare, Nabokov and Eliot. For a while, it seems as if Jacob Marlowe, tired to death (geddit?) with his moon-go-round immortality, will simply write himself into some sort of somatic torpor, since much of the backstory comes to us through his diary entries.

Along with the naughty bits we also get plenty of literary allusions, including everything from Marlowe's name itself to Shakespeare, Nabokov and Eliot. For a while, it seems as if Jacob Marlowe, tired to death (geddit?) with his moon-go-round immortality, will simply write himself into some sort of somatic torpor, since much of the backstory comes to us through his diary entries. Duncan maintains the immediacy that allows his novel to shine. As Marlowe tries to outwit the WOCOP agent who wants to wreak vengeance on him (Marlowe killed his father), his complicated, self-conscious but also self-aware voice is the thing that makes the story work. Duncan makes it work so well that it is a little too easy to forget how Jacob's musings on appetites versus restraint, creativity versus brutality, and so on are echoes not just of long-running literary arguments, but also of man's struggles with the divine.

Duncan maintains the immediacy that allows his novel to shine. As Marlowe tries to outwit the WOCOP agent who wants to wreak vengeance on him (Marlowe killed his father), his complicated, self-conscious but also self-aware voice is the thing that makes the story work. Duncan makes it work so well that it is a little too easy to forget how Jacob's musings on appetites versus restraint, creativity versus brutality, and so on are echoes not just of long-running literary arguments, but also of man's struggles with the divine.

Your protagonist, Jacob Marlowe, is a werewolf hunted by agents determined to end his 200-year-old life ("I was in Europe when Nietzsche and Darwin between them got rid of God"). What inspired you to combine Marlowe's efforts to foil repeated assaults with your own meditations on the themes of sex, death and transformation?

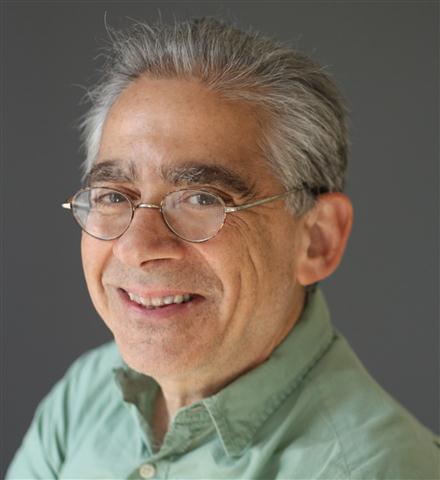

Your protagonist, Jacob Marlowe, is a werewolf hunted by agents determined to end his 200-year-old life ("I was in Europe when Nietzsche and Darwin between them got rid of God"). What inspired you to combine Marlowe's efforts to foil repeated assaults with your own meditations on the themes of sex, death and transformation? Knopf editor-at-large Marty Asher has worked at Random House since 1987, when he was hired by Sonny Mehta, who had just been given jurisdiction over Vintage by Random House's then-CEO, Bob Bernstein. Asher, who had been running the Book-of-the-Month Club, brought his formidable skills to bear on Vintage, publishing now-classic, handsomely designed paperback editions of novels by Cormac McCarthy, Richard Ford, Haruki Murakami, Nicholson Baker and Philip Roth that many of us have on our bookshelves to this day. In addition to his editing duties, Asher has also published novels of his own, including The Boomer (2000) and Shelter (1986).

Knopf editor-at-large Marty Asher has worked at Random House since 1987, when he was hired by Sonny Mehta, who had just been given jurisdiction over Vintage by Random House's then-CEO, Bob Bernstein. Asher, who had been running the Book-of-the-Month Club, brought his formidable skills to bear on Vintage, publishing now-classic, handsomely designed paperback editions of novels by Cormac McCarthy, Richard Ford, Haruki Murakami, Nicholson Baker and Philip Roth that many of us have on our bookshelves to this day. In addition to his editing duties, Asher has also published novels of his own, including The Boomer (2000) and Shelter (1986). How often does a novelist get music created for a novel? Not often, but The Last Werewolf has inspired a soundtrack by The Real Tuesday Weld. The album

How often does a novelist get music created for a novel? Not often, but The Last Werewolf has inspired a soundtrack by The Real Tuesday Weld. The album