What would you most like your American readers to take away from The Keeper of Lost Causes?

What would you most like your American readers to take away from The Keeper of Lost Causes?

Just as in the case of Mad Men, The Sopranos and other good series, I hope the reader gets to know the main characters so intimately that he or she practically cannot live without them once the book is read. That the reader will enter spheres of tension and excitement he hasn't experienced before, but is determined to carry on, even if it costs a couple of hours' sleep. That the reader can't help laughing one minute, only to be shivering with hair-raising suspense the next.

Carl Mørck is a wonderfully realized and nuanced character; he's dark, funny, vulnerable, tough, ironic, and completely human as he works to untangle the myriad complications of his many undefined relationships. Where did you get the inspiration for this terrific character?

Well, actually I'm not a crime-writer, I write thrillers, where everything can happen and where the primary intention is to prevent a crime from occurring, not "merely" solve it. So I needed to get rid of all the restrictions that a police officer has in his daily work in terms of narrow geographic divisions and what kind of crimes he is supposed to work on. I had to invent a character that nobody wanted to work with, so he could be on his own and do precisely as he wanted.

Back in the days when I was managing director of a big, Danish magazine publishing house that published Mad Magazine, among other things, I discussed with William H. Gaines (who created Mad) which cartoon strip was the best, and, funny enough, we pretty much agreed on "The Shadow Knows" by Sergio Aragonés, which consisted of very small and often simple cartoons with all sorts of folks in all kinds of daily situations, but where their shadows behind them projected (literally) their true thoughts and motives. This cartoon strip reflects everything we dream about being able to say straight to the face of our boss or to our kids, and it reflects in a nutshell the essence of both Carl Valdemar Jussi Henry Adler-Olsen and Carl Mørck. Therefore I decided a good portion of irony, satire and self-irony--combined with humor--were going to be important components of this main character.

However these characteristics--combined with great knowledge of, and experience in, police work, plus a dysfunctional private life--were not going to comprise the aggregate picture of Carl Mørck. My childhood at psychiatric hospitals (as son of psychiatrist head doctor Henry Olsen) taught me at an early age--actually through a deranged patient named Mørck--that good and evil are basic elements in all of us, and my memory of this patient's struggle with the evil inside him gave nourishment to an important portion of my main character, a police officer named Carl. So naturally he ended up being named Carl Mørck.

However these characteristics--combined with great knowledge of, and experience in, police work, plus a dysfunctional private life--were not going to comprise the aggregate picture of Carl Mørck. My childhood at psychiatric hospitals (as son of psychiatrist head doctor Henry Olsen) taught me at an early age--actually through a deranged patient named Mørck--that good and evil are basic elements in all of us, and my memory of this patient's struggle with the evil inside him gave nourishment to an important portion of my main character, a police officer named Carl. So naturally he ended up being named Carl Mørck.

Despite the horrific nature of the crime in The Keeper of Lost Causes, there are many moments of skillfully executed comic relief. How big a part, for you, does humor play in this novel?

The shortest distance between two people has always been laughter. A single person's laughter in a large gathering can infect everyone. Laughter can be heard at a distance of 500 feet and, when used conscientiously, can build bridges over everything. The Department Q series deals with many serious topics, and in that context humor serves a number of purposes. It creates some breathing room for the reader where the tension is a little too high. It builds bridges between the lead characters--Carl, Assad and, later, Rose--and it also builds bridges over the great chasm of political disagreements that are currently so prevalent in Denmark and many other places in the world. With humor you can avoid pedantry and superciliousness that never achieves anything positive, anyway.

Several characters in this novel struggle with disability, both intellectual and physical. Is this an important theme for you?

I think it was my childhood at the psychiatric hospitals that taught me to place so much value in knowing people whose lives are not at all like our own; it taught me that no two people are the same--nor should they be. These oddball types of every persuasion have awakened my empathy for--and understanding of--the fact that life can go in many directions. Tolerance is a precondition for positive interaction between people. If it were up to me, we'd all learn sign language and work to make it easier for our socially, mentally and physically handicapped fellow citizens to be different. What we get in return from these people cannot be gauged in terms of time or money. New ways of thinking, ideas and points of view arise. Simplified philosophies of life are made more complex, and complex values are toned down and made simpler. That's why I usually treat these people in Dept. Q's character register sympathetically.

Mørck's assistant, Assad, is such an intriguing character. On the surface, he seems quite guileless and naïve, but there is clearly a great deal of complexity just below this exterior and we see both sides revealed through his relationship with Mørck. How did that relationship develop as you wrote the novel?

Assad's story is one of Department Q's pivotal and most cryptic elements. He arose out of a single sentence that my good friend and translator Steve Schein said one day when I called him up and declared that I missed him and was thinking about him a lot. At which point he answered: "Hey Jussi, that's fantastic. Great minds work alike. I was just thinking about me, too."

I built up the offbeat character of Assad through this single sentence. He's like Don Quixote's sidekick, Sancho Panza. Alive, animated, full of dodges and quirks and the one who kick-starts a story. The relationship between Carl and Assad can be compared to that of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, though Assad is not completely Watsonian. Assad is employed as a unique kind of janitor for Carl. He seems simple-minded, but actually possesses a great sense of humor and is very intelligent, especially when it comes to his abilities in helping police investigations. Assad was "born" into the role of Carl's catalyst. He's the one who is able to get his work-weary superior interested in his job and life around him. And at the same time Assad is a perfect example of an immigrant who is the equal of any man and at least as well educated, and is not the least apprehensive about different cultures working side by side. Assad's long tale develops slowly from volume to volume in the series and is at least as exciting, bloody-minded and unpredictable as Carl's. Just wait!

What looms on the horizon next for Department Q?

Most importantly, a new colleague joins Dept. Q: the outlandish, willful Rose, who is able to control the whole department with her idiosyncratic, anarchistic demeanor, and Carl doesn't even notice. At least not at first.

The Department Q novels constitute one long, continuous thriller narrative with all the effects and tricks dramaturgy has to offer, built over a series of cases where each novel takes place in a new, unusual, hopefully never-seen-before location, with original characters and an original plot.

That's all I'm going to reveal, except that one day perhaps all the novels in the series will be remembered for their individually unique type of forward momentum, as well as their wild cases and chases.

Enjoy. --Debra Ginsberg

Carl Mørck is back at work after being on sick leave, an innocuous term for what had happened to him: on a dead-body call, he and two colleagues were gunned down. In only five minutes, "Anker lay on the floor in a pool of blood, Hardy had taken his last steps, and the fire inside Carl was extinguished--the fire that was absolutely essential for a detective in the homicide division of the Copenhagen Police." Mørck is no longer himself, the ace detective who lived and breathed his work; the tall, elegant man now has deep shadows under his eyes and an expression of profound indifference. At the station, he's argumentative and disruptive, and his fellow officers are fed up. But a plan emerges with a funding mandate from a government official, who has decreed that a new department, called Q, be set up to look into "cases deserving special scrutiny." Cold, hopeless cases. Perfect: put Mørck in charge and move him to the basement, far away from everyone.

Carl Mørck is back at work after being on sick leave, an innocuous term for what had happened to him: on a dead-body call, he and two colleagues were gunned down. In only five minutes, "Anker lay on the floor in a pool of blood, Hardy had taken his last steps, and the fire inside Carl was extinguished--the fire that was absolutely essential for a detective in the homicide division of the Copenhagen Police." Mørck is no longer himself, the ace detective who lived and breathed his work; the tall, elegant man now has deep shadows under his eyes and an expression of profound indifference. At the station, he's argumentative and disruptive, and his fellow officers are fed up. But a plan emerges with a funding mandate from a government official, who has decreed that a new department, called Q, be set up to look into "cases deserving special scrutiny." Cold, hopeless cases. Perfect: put Mørck in charge and move him to the basement, far away from everyone.

"It was a stupid case, full of inconsistencies... no plausible theories. No clear motive." But Mørck is pulled in, almost by the strength alone of Assad's will (and coffee). As they pursue leads, they combine skills-- not gracefully, but usually gratefully. Carl Mørck is complex, as one would expect, with a messy, dysfunctional life: separated from his wife but not divorced, he's funding her new whim, an art gallery. His stepson, a teenage slacker, lives with him; he suffers from survivor guilt about the shooting; he has occasional pains in his chest. He views his life, and the world around him, with a wry, mordant wit, through which we absorb lessons on Danish society and politics: "Whenever a case was rummaging around in his brain, it would be easier to track down a competent local politician than to make contact with Carl, and they all knew it." He questions a politician, and gets a sincere reaction, "As if somewhere inside that body, nourished on high-class reception delicacies, there still might be a human being."

"It was a stupid case, full of inconsistencies... no plausible theories. No clear motive." But Mørck is pulled in, almost by the strength alone of Assad's will (and coffee). As they pursue leads, they combine skills-- not gracefully, but usually gratefully. Carl Mørck is complex, as one would expect, with a messy, dysfunctional life: separated from his wife but not divorced, he's funding her new whim, an art gallery. His stepson, a teenage slacker, lives with him; he suffers from survivor guilt about the shooting; he has occasional pains in his chest. He views his life, and the world around him, with a wry, mordant wit, through which we absorb lessons on Danish society and politics: "Whenever a case was rummaging around in his brain, it would be easier to track down a competent local politician than to make contact with Carl, and they all knew it." He questions a politician, and gets a sincere reaction, "As if somewhere inside that body, nourished on high-class reception delicacies, there still might be a human being."

What would you most like your American readers to take away from The Keeper of Lost Causes?

What would you most like your American readers to take away from The Keeper of Lost Causes? However these characteristics--combined with great knowledge of, and experience in, police work, plus a dysfunctional private life--were not going to comprise the aggregate picture of Carl Mørck. My childhood at psychiatric hospitals (as son of psychiatrist head doctor Henry Olsen) taught me at an early age--actually through a deranged patient named Mørck--that good and evil are basic elements in all of us, and my memory of this patient's struggle with the evil inside him gave nourishment to an important portion of my main character, a police officer named Carl. So naturally he ended up being named Carl Mørck.

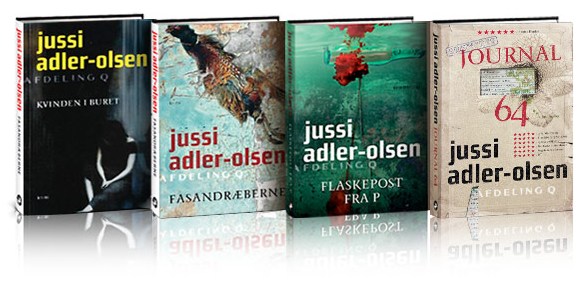

However these characteristics--combined with great knowledge of, and experience in, police work, plus a dysfunctional private life--were not going to comprise the aggregate picture of Carl Mørck. My childhood at psychiatric hospitals (as son of psychiatrist head doctor Henry Olsen) taught me at an early age--actually through a deranged patient named Mørck--that good and evil are basic elements in all of us, and my memory of this patient's struggle with the evil inside him gave nourishment to an important portion of my main character, a police officer named Carl. So naturally he ended up being named Carl Mørck. Jussi Adler-Olsen is Denmark's #1 thriller writer. His books routinely top the bestseller lists in northern Europe, and he's won just about every Nordic crime-writing award, including the prestigious Glass Key Award issued by the Crime Writers of Scandinavia--also won by Henning Mankell, Stieg Larsson and Peter Høeg--and the Golden Laurels, the most prestigious Danish Literary award, founded by the Danish booksellers. The first volume in the Department Q series, The Keeper of Lost Causes, hit the top of the bestseller lists in Denmark, Germany and Austria, the Netherlands and the U.K., and subsequent titles in the series also debuted at #1. It is now being released in the U.S. by Dutton (August 23, 2011).

Jussi Adler-Olsen is Denmark's #1 thriller writer. His books routinely top the bestseller lists in northern Europe, and he's won just about every Nordic crime-writing award, including the prestigious Glass Key Award issued by the Crime Writers of Scandinavia--also won by Henning Mankell, Stieg Larsson and Peter Høeg--and the Golden Laurels, the most prestigious Danish Literary award, founded by the Danish booksellers. The first volume in the Department Q series, The Keeper of Lost Causes, hit the top of the bestseller lists in Denmark, Germany and Austria, the Netherlands and the U.K., and subsequent titles in the series also debuted at #1. It is now being released in the U.S. by Dutton (August 23, 2011).