Born in the U.S., Patrick Ness has been living in England for 12 years. He has published books for adults in addition to his Chaos Walking trilogy, aimed at teens. Denise Johnstone-Burt, Ness's editor at Walker Books in the U.K., approached him about completing a project barely begun by Siobhan Dowd (A Swift Pure Cry), who died recently of breast cancer. We talked with Ness about why he took on A Monster Calls, which he initially thought could be "fraught with potential disaster," and how the seeds of what Dowd planted began to grow into a novel of his own.

Born in the U.S., Patrick Ness has been living in England for 12 years. He has published books for adults in addition to his Chaos Walking trilogy, aimed at teens. Denise Johnstone-Burt, Ness's editor at Walker Books in the U.K., approached him about completing a project barely begun by Siobhan Dowd (A Swift Pure Cry), who died recently of breast cancer. We talked with Ness about why he took on A Monster Calls, which he initially thought could be "fraught with potential disaster," and how the seeds of what Dowd planted began to grow into a novel of his own.

How far did Siobhan Dowd get with the story?

She had the characters--the tree, Conor, the mother and Lily, the friend--and a bit of starting prose to set the scene. She had the idea that there would be three stories within it--that was in an email [to Denise]. But she didn't say what those stories were. I thought, what would stories mean in this context? They were really potent starting ideas.

When I talk to young people, I say a good idea always attracts other good ideas. What Siobhan had was so potent, and exactly the right amount of material, that I said yes. I could see how the story could go and where I might take it.

In your foreword, you said that the directive you felt from Siobhan Dowd was "Go. Run with it. Make trouble." Why "Make trouble"?

I never liked stories where the bully makes friends with his victim. It wasn't happening in the world I lived in. The Chaos Walking trilogy has tough stuff, but you can still connect with someone and have a friendship that matters. When you really rely on someone, that can change the world. "Making trouble" in this context is about setting aside everything I thought I knew about mothers with illnesses. Sadly, this kind of thing happens to young people, and to soften it in any way is disrespectful. It can easily be sentimentalized. You can write it beautifully so you feel it less. The truth in this story is the sadness, and the anger about the fear of his loss. Fear of loss is corrosive and can be just as destructive as grief.

I think the job of any artist, but particularly the storyteller, is to look at the truth of your story and report what's actually there. Not what you would like to be there or expect to be there, but what's actually there. Stories organize the world. They are a way to make the world make sense.

Can you talk about the significance of the Green Man in British lore?

The yew tree isn't specifically the Green Man, but the Green Man is thousands of years old. He has lots of shapes, lots of entities--it's usually fertility. There's also a playfulness to him. The face of the Green Man is called a "foliate head," and carvings of him are in most country churches. I like that he's a slippery figure, there's not a specific Green Man tale. He's the physical manifestation of the countryside and greenery, and shifts in and out of folk songs and tales. There's some Green Man stuff in Jerusalem, too. The yew tree character was Siobhan's, and I thought, there's real richness here if you can link him back to this ancient ideal.

How did the three stories within the larger narrative take hold? Did Conor's dream come first, and then the monster's stories follow?

Conor's dream was always there. That was the foundation story, something that Conor grapples with. I was faced with having these three stories within it. It was fun actually, it's a sad book, but the stories were joyous. I liked the idea of folktales and taking what seems like a classic and making it my own version, and then in the next chapter tearing it to pieces. One of my favorite lines is when the monster says, "Sometimes witches merit saving. Quite often, actually. You'd be surprised."

Why 12:07?

It's a couple reasons. It's nice that it's after midnight. Monsters always come after midnight. It's nice that it's arbitrary. It's specificity. That's the interesting thing about dreams. There's one specific thing you hang onto. To give it an aura of "how real is this?" It's, I hope, lightly touched upon, so it's like comedy when the monster's late. It's a gateway for the monster to reenter the story. At the very, very end there's a question that maybe 12:07 has another meaning.

Were you pleased with the illustrations by Jim Kay?

Were you pleased with the illustrations by Jim Kay?

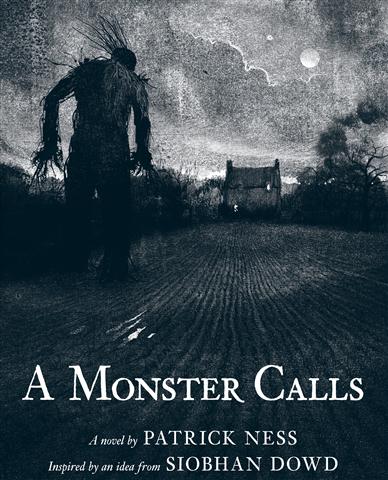

I think they're great! This is the first time I've worked with an illustrator. He hadn't ever illustrated a book before. We were talking about people who could be possible illustrators, and he had one of crows, an electricity pylon on his website. They were just right--the use of black-and-white, the mood. He includes details but they're also impressionistic.

The very first drawing he did was the one of the monster leaning against Conor's window. That hasn't changed. He got it exactly right, on the first try. I also love the illustration for the second story with the factory at the bottom of the valley, with the Apothecary walking up the hill. They're not so detailed that you can't put yourself into them.

Is there a difference in terms of your process, if you're writing for adults or for a younger audience, as with A Monster Calls?

When I've tried to second-guess what an audience wants, the story becomes functional and not the truth. If I tell it as truthfully as I can, then I think younger readers will get exactly as much as they want and need to get. What I wanted most as a young reader was the truth, and I wasn't getting it. I want to tell the truth for them. That to me is the most important thing. I regard that as a bit sacred.

Wasting not a word in a narrative leavened with humor, Patrick Ness describes the isolation that accompanies the feelings of grief, pain and anger in a child whose mother is battling a terminal illness.

Wasting not a word in a narrative leavened with humor, Patrick Ness describes the isolation that accompanies the feelings of grief, pain and anger in a child whose mother is battling a terminal illness. And, in the course of the third story, about an invisible man, the monster defeats Harry in the cafeteria. But the headmistress summons Conor (not the monster) to her office. Is the monster real or is he part of Conor? The brilliant illustration of Conor upending the lunchroom chairs depict him in the same position as the monster on his first visit to Conor's window, arms pressed forward and an energy coursing from his fingertips. What matters is that when Conor needs the monster most, he is there: Conor confides his nightmare to the monster, the fourth story. "I do not often come walking, boy, only for matters of life and death."

And, in the course of the third story, about an invisible man, the monster defeats Harry in the cafeteria. But the headmistress summons Conor (not the monster) to her office. Is the monster real or is he part of Conor? The brilliant illustration of Conor upending the lunchroom chairs depict him in the same position as the monster on his first visit to Conor's window, arms pressed forward and an energy coursing from his fingertips. What matters is that when Conor needs the monster most, he is there: Conor confides his nightmare to the monster, the fourth story. "I do not often come walking, boy, only for matters of life and death."

Born in the U.S., Patrick Ness has been living in England for 12 years. He has published books for adults in addition to his Chaos Walking trilogy, aimed at teens. Denise Johnstone-Burt, Ness's editor at Walker Books in the U.K., approached him about completing a project barely begun by Siobhan Dowd (

Born in the U.S., Patrick Ness has been living in England for 12 years. He has published books for adults in addition to his Chaos Walking trilogy, aimed at teens. Denise Johnstone-Burt, Ness's editor at Walker Books in the U.K., approached him about completing a project barely begun by Siobhan Dowd ( Were you pleased with the illustrations by Jim Kay?

Were you pleased with the illustrations by Jim Kay?  "It's thrilling and intimidating," says Kaylan Adair about working with Patrick Ness. As his American editor, she's worked with Ness since The Knife of Never Letting Go, the first in his Chaos Walking trilogy. She and Denise Johnstone-Burt, his British editor at Walker Books, work closely with Ness on his books. Adair describes him as "a genius," yet he's also open to suggestion and discussion. "Down to the last detail, he's thought things through so carefully," Adair says. "You get such insight into how his mind works."

"It's thrilling and intimidating," says Kaylan Adair about working with Patrick Ness. As his American editor, she's worked with Ness since The Knife of Never Letting Go, the first in his Chaos Walking trilogy. She and Denise Johnstone-Burt, his British editor at Walker Books, work closely with Ness on his books. Adair describes him as "a genius," yet he's also open to suggestion and discussion. "Down to the last detail, he's thought things through so carefully," Adair says. "You get such insight into how his mind works." Jim Kay's artwork for A Monster Calls also unfolds in shades of gray. "Anyone that watches horror movies knows that it's what you don't see that frightens you the most," says Kay, so he avoided showing too much of the monster in any one scene. That also allowed him to toggle between the creature's monster characteristics and his more human qualities. Kay felt that his early drawings depicted the monster as "too spindly, too manic. But from those came the idea to give him a scalp like a pollarded tree, and hands resembling a tangle of unearthed roots, complete with clumps of soil."

Jim Kay's artwork for A Monster Calls also unfolds in shades of gray. "Anyone that watches horror movies knows that it's what you don't see that frightens you the most," says Kay, so he avoided showing too much of the monster in any one scene. That also allowed him to toggle between the creature's monster characteristics and his more human qualities. Kay felt that his early drawings depicted the monster as "too spindly, too manic. But from those came the idea to give him a scalp like a pollarded tree, and hands resembling a tangle of unearthed roots, complete with clumps of soil." On your nightstand now:

On your nightstand now: