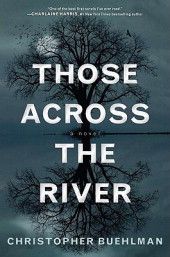

Those Across the River by Christopher Buehlman (Ace, $24.95, 9780441020676, September 6, 2011)

Christopher Buehlman's masterful debut novel opens with an unsettling preface: "He came out to see me in the cage because I belonged to him." The caged man mutters that he's not good enough to eat. The man on the outside replies, "Maybe just your heart."

Christopher Buehlman's masterful debut novel opens with an unsettling preface: "He came out to see me in the cage because I belonged to him." The caged man mutters that he's not good enough to eat. The man on the outside replies, "Maybe just your heart."

Were it not for that tip-off, one would think that Christopher Buehlman had written "just" a fine novel about a couple from Chicago moving to a small Georgia town in the mid-1930s. Frank Nichols is 36, a World War I vet troubled by war nightmares, a college history professor unable to find work because of his affair with 24-year-old Eudora, who was married to an older, influential professor at Frank's college. When Frank inherits a house in Georgia from his aunt, he and Dora decide a move will give them a fresh start--she'll teach school while Frank works on a book about his slave-owning great-grandfather, Lucien Savoyard, whose ruined plantation is nearby. Their backstory is compelling, and their arch but affectionate conversations à la Loy and Powell underscore their deep intellectual and sexual connection.  The small Southern town and its people are well-drawn: Paul Miller, the affable fat man who owns the general store; Miles Falmouth, whose bad back grieves him "positively Ole Tessament"; Sheriff Estel Blake, the compassionate hardware store owner; and Martin Cranmer, taxidermist, chess player, drinker, with his dark beard and ill-fitting cream-colored suit. And a secret. He tells Frank, "You don't know anything about it" when he's questioned about the slave revolt at the Savoyard plantation. "You ought to leave your general alone. Might not like what you find."

The small Southern town and its people are well-drawn: Paul Miller, the affable fat man who owns the general store; Miles Falmouth, whose bad back grieves him "positively Ole Tessament"; Sheriff Estel Blake, the compassionate hardware store owner; and Martin Cranmer, taxidermist, chess player, drinker, with his dark beard and ill-fitting cream-colored suit. And a secret. He tells Frank, "You don't know anything about it" when he's questioned about the slave revolt at the Savoyard plantation. "You ought to leave your general alone. Might not like what you find."

Buehlman's prose is moody and lush--sun gleaming through the pines, honey-thick air, the whirr of locusts, sweat- and sex-damp sheets, a milky moon. "The tree shadows stretched long and finger-like on the dirt road that led into Whitbrow as the last light of the day spilled from the west. The few houses that lined the road were really little better than shacks, but even they looked worthy of portraiture with that amber glow washing over their pine-board and tin." He can jolt with a few finely honed lines about the war: "The book of Revelations read like fairy-tale poetry next to this harsh prose." Or, the Huns "ready to send a rosary of lead that could make whole companies kneel." And he can be witty: when Frank asks the storekeeper for wine, he's told there's no wine in Morgan County--"All we drink is the blood of the Redeemer." And shine.

Story, sense of place, drama, sensuality, smoldering prose, characters in both senses of the word, pitch-perfect dialogue--these elements alone would be enough to recommend Those Across the River to readers. But as the preface infers, Buehlmann has a few chilling curves to throw into a seemingly straightforward tale.

First, there's the letter from his aunt willing him the house, but saying that he must sell it. No reason given, just that there is bad blood in Whitbrow, and it will "smell out" what is in him. He ignores her demand--he is disgraced and Dora is an inexperienced teacher. What other options do they have?

Soon after they settle in, Frank goes for a walk through the pine and red clay woods with Lester Goudreau, who's offered to show him the river--the plantation is on the other side--but Lester won't cross the river: "Them woods is deep and mean." Later, Frank and Dora are told about the Chase. It starts at the church, with a hog and a sow decorated with wildflower wreaths, and blessed by Pastor Lyndon. The pigs are led down to the river, followed by the townsfolk singing unfamiliar hymns, and then taken across and turned loose. It seems a bit pagan, but Frank and Dora consider it charming local color.

Soon after they settle in, Frank goes for a walk through the pine and red clay woods with Lester Goudreau, who's offered to show him the river--the plantation is on the other side--but Lester won't cross the river: "Them woods is deep and mean." Later, Frank and Dora are told about the Chase. It starts at the church, with a hog and a sow decorated with wildflower wreaths, and blessed by Pastor Lyndon. The pigs are led down to the river, followed by the townsfolk singing unfamiliar hymns, and then taken across and turned loose. It seems a bit pagan, but Frank and Dora consider it charming local color.

A few days after the Chase, Frank decides to cross the river and look for the Savoyard plantation ruins, a plan Dora doesn't like, saying the woods aren't friendly. Frank agrees, but still goes, thinking about his best friend, Tom, who died in the war. "We were so goddamned eager to go. We were so stupid." As he walks through the dense forest, he has a feeling of being watched, and finally sees a pale mulatto boy wearing a dirty shirt and no pants. The boy follows him, throws stones at him, and then smiles. His teeth have been filed sharp. That readily convinces Frank to find his way back across the river, ending up at Cranmer's cabin, where the windows are barred and the door is heavy oak. Cranmer tells him to get away, to run home, and stay there. He does, as the moon rises fat and golden.

Frank manages to rationalize everything he's seen, until August, with the town's discussion about stopping the Chase. Times are tight, and a farmer can ill afford to give up two pigs. The debate is heated, but the aldermen finally vote to end the Chase. The morning after the next full moon, though, the town finds that Miles Falmouth's son was killed that night, trying to scare off something that was after their pigs. A posse with dogs leaves to nose out the killer. They find a man, and they think it's over.

Frank manages to rationalize everything he's seen, until August, with the town's discussion about stopping the Chase. Times are tight, and a farmer can ill afford to give up two pigs. The debate is heated, but the aldermen finally vote to end the Chase. The morning after the next full moon, though, the town finds that Miles Falmouth's son was killed that night, trying to scare off something that was after their pigs. A posse with dogs leaves to nose out the killer. They find a man, and they think it's over.

In September, five new shovels are stolen from the hardware store, along with some kerosene and rope. The town doesn't have long to wonder why, because the message soon sent to them is unambiguous: SEND THE PIGS--and the medium is horrifying. So 15 men and boys set off for the woods to roust out whoever is responsible for the outrage. Frank is afraid that "whoever" is actually "whatever."

In this spellbinding tale of terror, Christopher Buehlman traces with impeccable pacing the arc from the happiness of a new beginning for Frank and Dora through hints of lurking strangeness in their new town, to full-blown horror as evil is unleashed when Whitbrow's careful balance is upset. One character says to Frank, "Alas. That is a good word. Full of helplessness and beauty." Those Across the River is filled with cowardice and bravery, foolishness and wisdom, grief and grace, and, alas, helplessness and beauty. Buehlman has written one of the best books of the year. --Marilyn Dahl

Christopher Buehlman's masterful debut novel opens with an unsettling preface: "He came out to see me in the cage because I belonged to him." The caged man mutters that he's not good enough to eat. The man on the outside replies, "Maybe just your heart."

Christopher Buehlman's masterful debut novel opens with an unsettling preface: "He came out to see me in the cage because I belonged to him." The caged man mutters that he's not good enough to eat. The man on the outside replies, "Maybe just your heart." The small Southern town and its people are well-drawn: Paul Miller, the affable fat man who owns the general store; Miles Falmouth, whose bad back grieves him "positively Ole Tessament"; Sheriff Estel Blake, the compassionate hardware store owner; and Martin Cranmer, taxidermist, chess player, drinker, with his dark beard and ill-fitting cream-colored suit. And a secret. He tells Frank, "You don't know anything about it" when he's questioned about the slave revolt at the Savoyard plantation. "You ought to leave your general alone. Might not like what you find."

The small Southern town and its people are well-drawn: Paul Miller, the affable fat man who owns the general store; Miles Falmouth, whose bad back grieves him "positively Ole Tessament"; Sheriff Estel Blake, the compassionate hardware store owner; and Martin Cranmer, taxidermist, chess player, drinker, with his dark beard and ill-fitting cream-colored suit. And a secret. He tells Frank, "You don't know anything about it" when he's questioned about the slave revolt at the Savoyard plantation. "You ought to leave your general alone. Might not like what you find." Soon after they settle in, Frank goes for a walk through the pine and red clay woods with Lester Goudreau, who's offered to show him the river--the plantation is on the other side--but Lester won't cross the river: "Them woods is deep and mean." Later, Frank and Dora are told about the Chase. It starts at the church, with a hog and a sow decorated with wildflower wreaths, and blessed by Pastor Lyndon. The pigs are led down to the river, followed by the townsfolk singing unfamiliar hymns, and then taken across and turned loose. It seems a bit pagan, but Frank and Dora consider it charming local color.

Soon after they settle in, Frank goes for a walk through the pine and red clay woods with Lester Goudreau, who's offered to show him the river--the plantation is on the other side--but Lester won't cross the river: "Them woods is deep and mean." Later, Frank and Dora are told about the Chase. It starts at the church, with a hog and a sow decorated with wildflower wreaths, and blessed by Pastor Lyndon. The pigs are led down to the river, followed by the townsfolk singing unfamiliar hymns, and then taken across and turned loose. It seems a bit pagan, but Frank and Dora consider it charming local color. Frank manages to rationalize everything he's seen, until August, with the town's discussion about stopping the Chase. Times are tight, and a farmer can ill afford to give up two pigs. The debate is heated, but the aldermen finally vote to end the Chase. The morning after the next full moon, though, the town finds that Miles Falmouth's son was killed that night, trying to scare off something that was after their pigs. A posse with dogs leaves to nose out the killer. They find a man, and they think it's over.

Frank manages to rationalize everything he's seen, until August, with the town's discussion about stopping the Chase. Times are tight, and a farmer can ill afford to give up two pigs. The debate is heated, but the aldermen finally vote to end the Chase. The morning after the next full moon, though, the town finds that Miles Falmouth's son was killed that night, trying to scare off something that was after their pigs. A posse with dogs leaves to nose out the killer. They find a man, and they think it's over. Tom Colgan is an executive editor at Penguin. Over a 25-year publishing career he has worked with many authors, including Clive Cussler, Ed McBain and Tom Clancy. He's edited numerous books that have been bestsellers and won Edgar, Anthony and Stoker Awards as well. He's a lifelong New Yorker who is only three days younger than his beloved New York Mets. You can follow him on Twitter @TomColgan14.

Tom Colgan is an executive editor at Penguin. Over a 25-year publishing career he has worked with many authors, including Clive Cussler, Ed McBain and Tom Clancy. He's edited numerous books that have been bestsellers and won Edgar, Anthony and Stoker Awards as well. He's a lifelong New Yorker who is only three days younger than his beloved New York Mets. You can follow him on Twitter @TomColgan14. Your narrator is a WWI veteran subject to bouts of shell shock. His aunt left him her house in rural Georgia but warned, "Don't come back, whatever you do"; he disregards her orders. What inspired you to take Frank's dual attitudes of "I've seen the worst already" and "I have nothing left to lose," and plant him in Whitbrow, Ga., during the Great Depression?

Your narrator is a WWI veteran subject to bouts of shell shock. His aunt left him her house in rural Georgia but warned, "Don't come back, whatever you do"; he disregards her orders. What inspired you to take Frank's dual attitudes of "I've seen the worst already" and "I have nothing left to lose," and plant him in Whitbrow, Ga., during the Great Depression?