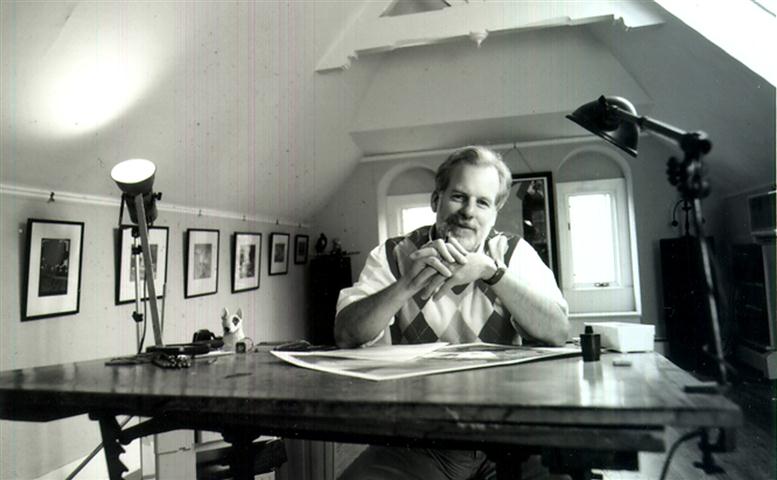

"I'm a rational person and believe in the virtues of science and reason," Van Allsburg said, "but there's something about things that are inexplicable that hold your attention." His exploration of the inexplicable has held readers' attention from his very first book, The Garden of Abdul Gasazi, in which the boy hero is left wondering if Gasazi is a sleight-of-hand master or a true wizard. Here he expands upon his fascination with the inexplicable, and the enduring appeal of the enigmatic Harris Burdick.

"I'm a rational person and believe in the virtues of science and reason," Van Allsburg said, "but there's something about things that are inexplicable that hold your attention." His exploration of the inexplicable has held readers' attention from his very first book, The Garden of Abdul Gasazi, in which the boy hero is left wondering if Gasazi is a sleight-of-hand master or a true wizard. Here he expands upon his fascination with the inexplicable, and the enduring appeal of the enigmatic Harris Burdick.

How did the idea for the original The Mysteries of Harris Burdick evolve?

One of the inspirations grew out of experiences I had at flea markets with dealers of ephemera--posters, postcards, small matted images that have come out of books. If they take out the 20 illustrations and matte each one separately and sell them for $10, they'll make more, so they cannibalize the book. One of these dealers had some Gustave Doré sort of works, and he'd matted them in a way that retained the caption. The addition of a few words to this image was like putting a match to the thing--not to destroy it, but to create some heat.

It's amazing that an image that could be perhaps banal and a caption that's perhaps banal as well can interact in a way that triggers the imagination to make sense of the two things together. It's a kind of alchemy; they catalyze each other. That's the best thing about picture books—the way the words and images heighten each other.

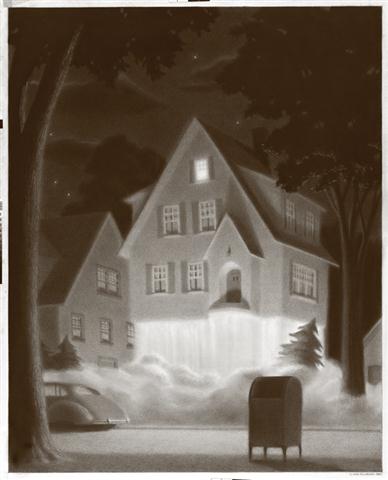

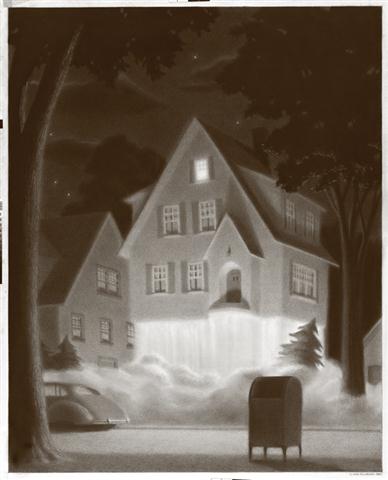

Stephen King must have been similarly inspired by your image and caption for "The House on Maple Street" when he wrote a story based on it (published in 1993).

Stephen King must have been similarly inspired by your image and caption for "The House on Maple Street" when he wrote a story based on it (published in 1993).

The introduction [to Mysteries] was embraced by the King family. Stephen, his wife, Tabitha, and his son wrote stories. When he was putting together the short story anthology Nightmares & Dreamscapes, he decided to include the Burdick story that he'd written. He asked if I would give permission to have this happen. I said absolutely! By that point, I'd received thousands of stories in the mail from kids. I thought it would be great to have a higher profile storyteller demonstrate the effect of this caption and picture on him, and his psychology.

And how did this new project, The Chronicles of Harris Burdick evolve?

A couple years ago, Margaret Raymo, my editor, said, "What would you think of asking Stephen King to republish his story as part of a collection and approach some other authors?" I was absolutely for it. "The House on Maple Street" was off the table, and "Archie Smith, Boy Wonder" was also off the table. [Tabitha King had written a story for it.] I told Margaret I wanted everyone to have a choice. The one left behind would be mine.

So "Oscar and Alphonse" was the last one left, for you to write? That's surprising—the theme of your story so strongly echoes Harris Burdick's.

So "Oscar and Alphonse" was the last one left, for you to write? That's surprising—the theme of your story so strongly echoes Harris Burdick's.

Like a politician, it doesn't matter what question you're asked, you have your answer. As an artist, if you have a theme you're working on, that's the one you're going to develop. I was reprising the theme of the original Harris Burdick [project]--things that don't get finished. The Farkas Conjecture in "Oscar and Alphonse" never really gets completed. The same narrative cycle continues. With the caterpillars, my idea was to create some ambiguity. There's a perplexing moment for the father and brothers: Is this truly magical--that caterpillars can do higher metaphysical physics? Or was the sister who shares the same genetic material capable of this kind of thinking, and the caterpillars create random movements, but she reveals her intellect by communicating with nature rather than by herself?

Then it would not have mattered which picture was left for you?

The interesting thing is that there are as many stories as there are people who hold them. It's like the Thematic Apperception Test. It's more specific than Rorschach but it works the same way. In that test, the psychologist uses photographs that are staged. A man, woman and child would be involved in an ambiguous interaction, and the psychologist says, "Tell me what's happening in this picture." The child would describe something that would reveal a reality about the child's own family dynamic. That's what happens anytime someone writes a Burdick story.

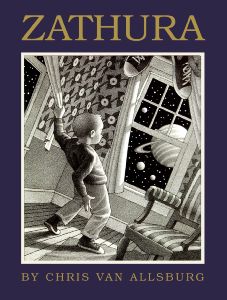

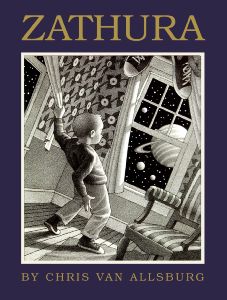

If the 14 of us all did it again but it was like musical chairs, then there'd be 14 volumes--14 versions of a single story. That really shows clearly how different people's imaginations can vary given the exact same stimulation. I realized later that Zathura could have been my "The House on Maple Street."

If the 14 of us all did it again but it was like musical chairs, then there'd be 14 volumes--14 versions of a single story. That really shows clearly how different people's imaginations can vary given the exact same stimulation. I realized later that Zathura could have been my "The House on Maple Street."

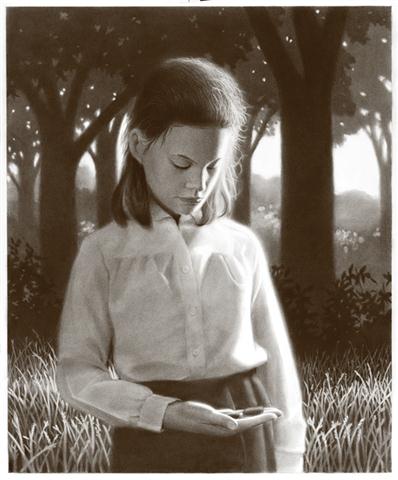

You render most of your work in black-and-white. Why?

In college, all I did was make sculpture, and I drew my studies for the sculptures in black and white. Then I decided as a lark to do some drawing and ultimately ended up doing The Garden of Abdul Gasazi. I remember when it came out, there were laudatory reviews about the intelligent choice of the artist to use black and white because it reinforced the slightly surreal theme. But it was a decision made of limitation.

If you use black and white on a highly representational style, you end up creating things with a different quality of light, because you're only using contrast rather than color. You're not sure exactly what time of day it is or what the sky's like underneath. It has that surreal quality I'm drawn to as a storyteller and a picture maker. As each year goes by, it gets stranger to see things in black and white. It's almost been banished from the visual landscape. As it becomes scarcer and scarcer, it's strangeness will become greater and greater.

Your exploration of artwork as a representation of reality often feels more real than what we experience.

There is a quality to art that's a little like magic. I've always been attracted to trompe l'oeil and optical illusion. The idea of artist as magician has always appealed to me, and there's a playfulness to that. Not to trifle with the reader or onlooker, but to point out that imagination and reality do overlap, and permeate each other in ways that art sometimes can reveal. I think people think if they're awake it's reality, and if they're dreaming they're not in reality. There's a lot going on when you're awake that's driven by the subconscious. It's true even on the level of perception. Oliver Sachs writes about subjects like that--how the brain is processing the stimuli that it gets. In some ways, art can facilitate people's experience of that.

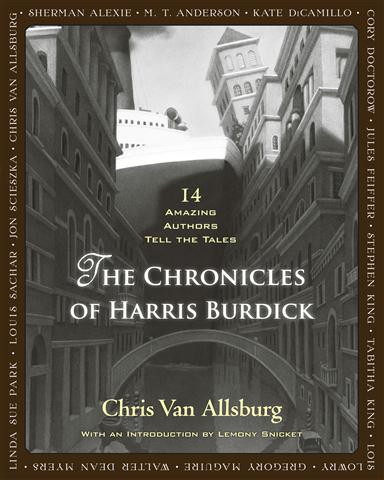

More than 25 years ago, Chris Van Allsburg published the original The Mysteries of Harris Burdick--a set of 14 drawings connected only by their elusive quality and a caption that suggests that each is part of a larger story. Van Allsburg's introduction explained that Harris Burdick had met with an editor, Peter Wenders, and showed him one image each from 14 stories he'd written and illustrated. Wenders expressed interest in the project and invited Burdick to bring him the rest. Burdick said he'd be back the next day. He was never seen or heard from again.

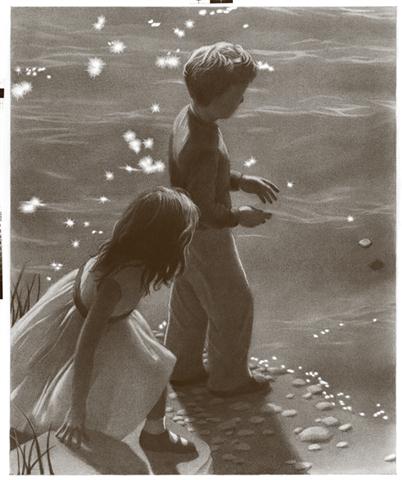

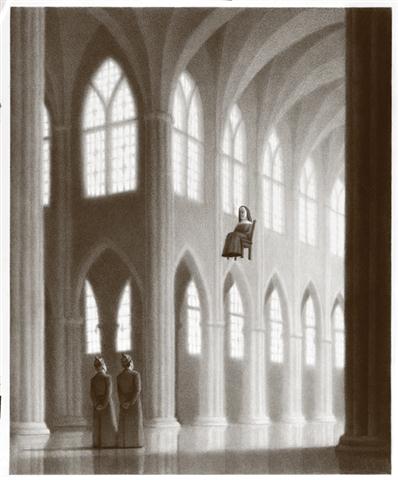

More than 25 years ago, Chris Van Allsburg published the original The Mysteries of Harris Burdick--a set of 14 drawings connected only by their elusive quality and a caption that suggests that each is part of a larger story. Van Allsburg's introduction explained that Harris Burdick had met with an editor, Peter Wenders, and showed him one image each from 14 stories he'd written and illustrated. Wenders expressed interest in the project and invited Burdick to bring him the rest. Burdick said he'd be back the next day. He was never seen or heard from again. Jon Scieszka's "Under the Rug" is the first of three stories that reveal how much we use laughter as a release from fear and anxiety. His narrator's grandmother spews so many clichés that the boy rarely heeds them. But how he wishes he'd taken her advice to "Never sweep a problem under the rug"--a tale with a scary-funny resolution that only Scieszka could deliver. Lois Lowry suggests in "The Seven Chairs" that girl babies are born to levitate, they just forget how--except for Mary Katherine Maguire, who hones her skill with entertaining results and takes the idea of the flying nun to a whole new level. Pearlie's brother has gone to war and left her with "fat-ankled Aunt Hazel" in "The Third-Floor Bedroom" by Kate DiCamillo. When Pearlie falls ill, the walls that confine her spur a transformation, and the author allows the girl's mask to fall away, revealing a depth beneath Pearlie's unflappable veneer.

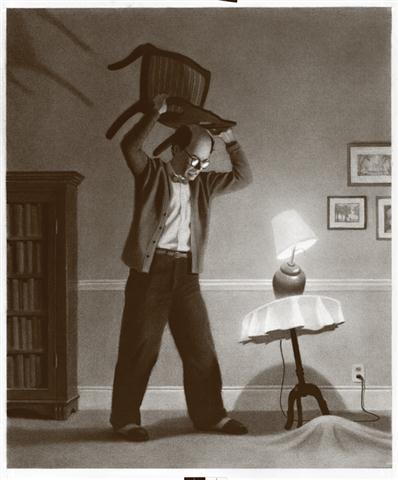

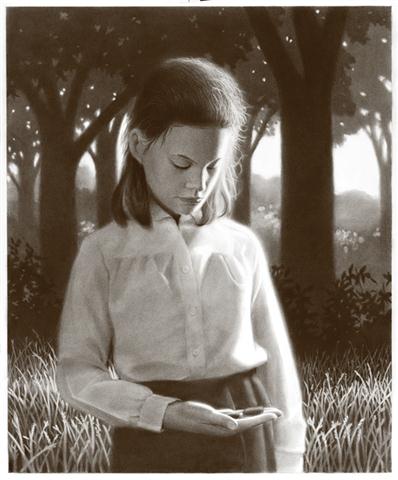

Jon Scieszka's "Under the Rug" is the first of three stories that reveal how much we use laughter as a release from fear and anxiety. His narrator's grandmother spews so many clichés that the boy rarely heeds them. But how he wishes he'd taken her advice to "Never sweep a problem under the rug"--a tale with a scary-funny resolution that only Scieszka could deliver. Lois Lowry suggests in "The Seven Chairs" that girl babies are born to levitate, they just forget how--except for Mary Katherine Maguire, who hones her skill with entertaining results and takes the idea of the flying nun to a whole new level. Pearlie's brother has gone to war and left her with "fat-ankled Aunt Hazel" in "The Third-Floor Bedroom" by Kate DiCamillo. When Pearlie falls ill, the walls that confine her spur a transformation, and the author allows the girl's mask to fall away, revealing a depth beneath Pearlie's unflappable veneer. Several stories deliver justice through comeuppance. The terrible twins in "A Strange Day in July" by Sherman Alexie invent a triplet that strikes terror in the hearts of their parents, classmates and teacher--and eventually its siblings. A book wields the power in "Mr. Linden's Library" by Walter Dean Myers. The retired merchant seaman of the title tells young Carol Jenkins she's welcome to borrow any book from his collection--except the one that's lying open. Some books "capture more of the mind than one would want to surrender," he warns. (This tale may cause you to reassess your reading habits.) In a way, the caterpillar stars of "Oscar and Alphonse: The Farkas Conjecture" by Chris Van Allsburg get the last word ("spelling out 'goodbye' ") when they leave an open question--in more ways than one.

Several stories deliver justice through comeuppance. The terrible twins in "A Strange Day in July" by Sherman Alexie invent a triplet that strikes terror in the hearts of their parents, classmates and teacher--and eventually its siblings. A book wields the power in "Mr. Linden's Library" by Walter Dean Myers. The retired merchant seaman of the title tells young Carol Jenkins she's welcome to borrow any book from his collection--except the one that's lying open. Some books "capture more of the mind than one would want to surrender," he warns. (This tale may cause you to reassess your reading habits.) In a way, the caterpillar stars of "Oscar and Alphonse: The Farkas Conjecture" by Chris Van Allsburg get the last word ("spelling out 'goodbye' ") when they leave an open question--in more ways than one.

"I'm a rational person and believe in the virtues of science and reason," Van Allsburg said, "but there's something about things that are inexplicable that hold your attention." His exploration of the inexplicable has held readers' attention from his very first book, The Garden of Abdul Gasazi, in which the boy hero is left wondering if Gasazi is a sleight-of-hand master or a true wizard. Here he expands upon his fascination with the inexplicable, and the enduring appeal of the enigmatic Harris Burdick.

"I'm a rational person and believe in the virtues of science and reason," Van Allsburg said, "but there's something about things that are inexplicable that hold your attention." His exploration of the inexplicable has held readers' attention from his very first book, The Garden of Abdul Gasazi, in which the boy hero is left wondering if Gasazi is a sleight-of-hand master or a true wizard. Here he expands upon his fascination with the inexplicable, and the enduring appeal of the enigmatic Harris Burdick. Stephen King must have been similarly inspired by your image and caption for "The House on Maple Street" when he wrote a story based on it (published in 1993).

Stephen King must have been similarly inspired by your image and caption for "The House on Maple Street" when he wrote a story based on it (published in 1993).  So "Oscar and Alphonse" was the last one left, for you to write? That's surprising—the theme of your story so strongly echoes Harris Burdick's.

So "Oscar and Alphonse" was the last one left, for you to write? That's surprising—the theme of your story so strongly echoes Harris Burdick's.  If the 14 of us all did it again but it was like musical chairs, then there'd be 14 volumes--14 versions of a single story. That really shows clearly how different people's imaginations can vary given the exact same stimulation. I realized later that Zathura could have been my "The House on Maple Street."

If the 14 of us all did it again but it was like musical chairs, then there'd be 14 volumes--14 versions of a single story. That really shows clearly how different people's imaginations can vary given the exact same stimulation. I realized later that Zathura could have been my "The House on Maple Street." After Margaret Raymo's daughter was assigned to write a story based on one of The Mysteries of Harris Burdick in her third-grade class, the editor got an idea. She asked Chris Van Allsburg what he thought about publishing a collection of stories based on his artwork from Mysteries. "That's when he told me about the Stephen King story," Raymo said.

After Margaret Raymo's daughter was assigned to write a story based on one of The Mysteries of Harris Burdick in her third-grade class, the editor got an idea. She asked Chris Van Allsburg what he thought about publishing a collection of stories based on his artwork from Mysteries. "That's when he told me about the Stephen King story," Raymo said. Like Van Allsburg, Lois Lowry had been edited for many years by Walter Lorraine and had known both the author-artist and his Mysteries since the book's inception. Lowry's grandchildren had also used the book in school, but she made some demands. "I was delighted to be included," Lowry said, "but only, I told Margaret, if I could have the floating nun! That nun had fascinated me for years."

Like Van Allsburg, Lois Lowry had been edited for many years by Walter Lorraine and had known both the author-artist and his Mysteries since the book's inception. Lowry's grandchildren had also used the book in school, but she made some demands. "I was delighted to be included," Lowry said, "but only, I told Margaret, if I could have the floating nun! That nun had fascinated me for years."