In its citation for David Almond's 2010 Hans Christian Andersen Award, the jury noted his "unique voice as a creator of magic realism for children." He balks at the idea of trying to categorize his work--though he acknowledges the influence of writers like García Márquez, Borges and Calvino. But for him, "the primary thing about my books is the realism. They're straightforward, ordinary people in ordinary places, but inside them are extraordinary things." Almond never planned to return to Skellig or its characters. But when editor Beverly Horowitz called him to ask if he could add a little something for the 10th anniversary edition, Mina was waiting for him.

In its citation for David Almond's 2010 Hans Christian Andersen Award, the jury noted his "unique voice as a creator of magic realism for children." He balks at the idea of trying to categorize his work--though he acknowledges the influence of writers like García Márquez, Borges and Calvino. But for him, "the primary thing about my books is the realism. They're straightforward, ordinary people in ordinary places, but inside them are extraordinary things." Almond never planned to return to Skellig or its characters. But when editor Beverly Horowitz called him to ask if he could add a little something for the 10th anniversary edition, Mina was waiting for him.

Can we back up just a bit and talk about the inspiration for Skellig? You had written primarily for adults before that.

I'd written for adults--a lot of short stories, and a novel that had been rejected by everybody. Then I wrote some stories about my own childhood, [later] published as Counting Stars. Just after that, Skellig started telling itself. It had lots of realistic bases. It's set in a house where I lived and drew on elements of my own life. Mina came into Skellig to my total surprise. She's the one who brought in [William] Blake and education and birds. Without Mina, Skellig would have been a sloppy book. She gave it a rigor and an alertness. People often say, "Who's your favorite character?" For me, it's always been Mina.

Did you find that you revisited Skellig to jumpstart Mina's story? Or was her story so strong in your mind that you didn't have to go back?

Did you find that you revisited Skellig to jumpstart Mina's story? Or was her story so strong in your mind that you didn't have to go back?

When I got to the end of her book, I needed to check the chronology of Skellig and some of the things Mina said in Skellig. In many ways, I wanted it to be separate because Mina knew nothing of Skellig [when her book takes place]. I didn't want to do lots of explanation of why Skellig was who he was. It had to be an explanation of who Mina was.

Mina is a special kid, and special kids often have a rough time at school fitting in with their peers and their teachers. But we also see how easily she connects with people who "get" her. Did you know kids like Mina?

She was a fascinating character to deal with. When she came into Skellig, I hadn't expected her to arrive. She came fully formed. She was imaginative, wacky, intelligent, very scientific on the one hand, and on the other hand very spiritual. When I wrote My Name Is Mina, I made some discoveries, like the sadness she had, and her character being shaped by the difficulties she'd had. While she seemed tough and confident, she's a very brave kind of child. I haven't known anybody like Mina, but I've known many kids who've had trouble fitting in, finding their way in the world.

Everyone wants to talk about Skellig, no matter what I come to talk about, and children say, "Mina was so wonderful and helpful to me." She was weirdly helpful to me, too. She's a creature of the imagination. Sometimes when I've had to answer questions about education and stuff, I'd find myself saying, "What would Mina say about that?"

For Mina, the coal mines are very much alive, filled with the spirits of Persephone and Hades. You grew up in a coal-mining town. Does the lore of those towns continue to shape its people? The mines factor into your books Kit's Wilderness and Heaven Eyes, too.

I think it does. It 's hard to say how it does. When Mina goes into the park, it's based on a real park. Part of the Victoria Tunnel [on which this one's based] has been reopened and people can visit. The tunnel goes underneath the park and through the city. The miners traveled it to go from pit to pit. Psychically, that tunnel is there inside people's imaginations. It will never go away, the fact that people used to go into the dark and bring out the coal. For me as a writer, it ties so nicely into the Persephone myth. I think that's why the myths are so powerful, they keep coming back and back and tell us more about ourselves, but they're also incredibly contemporary.

Tell us about "A Miner's Lullaby," which Mr. Henderson, the history teacher, sings.

I didn't know it very well at all, but when I wrote Mina I knew I needed a song that would do that job, so I went looking for it. I talked to a friend who knew old folk songs. The song is quite well known. On YouTube, there are a lot of examples of "A Miner's Lullaby." It's about a pitman cradling his daughter; it's a lovely song.

Mina often cites this quote from William Blake: "How can a bird that is born for joy/ sit in a cage and sing?" It's in Skellig, too. You create layers of meaning behind this phrase that reverberate within this book and also in Skellig.

Mina often cites this quote from William Blake: "How can a bird that is born for joy/ sit in a cage and sing?" It's in Skellig, too. You create layers of meaning behind this phrase that reverberate within this book and also in Skellig.

That was one of the things that had to find its way into this book. In Skellig, Mina says she has the Blake quote pinned to the wall. It's such a great thing--for Skellig and Mina--because of the bird imagery, and it says so much about education, growth and song. When you're writing, sometimes things come like gifts. Those two lines from Blake stand for the whole book. And he wrote them 100 years ago.

In your books, you grapple with the paradoxes of being human, the tension between creation and destruction, and through Mina, conformity and nonconformity. Her situation suggests that we need society, but only the society of those whose company we desire and who desire ours.

Mina doesn't fit in, and she expresses something very important about education. While everyone believes in education, schools aren't the perfect way to learn things. The world's more mysterious than we try to reduce it to. She's a worldly girl. She's attached to objects and people, but she also sees the miraculousness of the world, like birds and language.

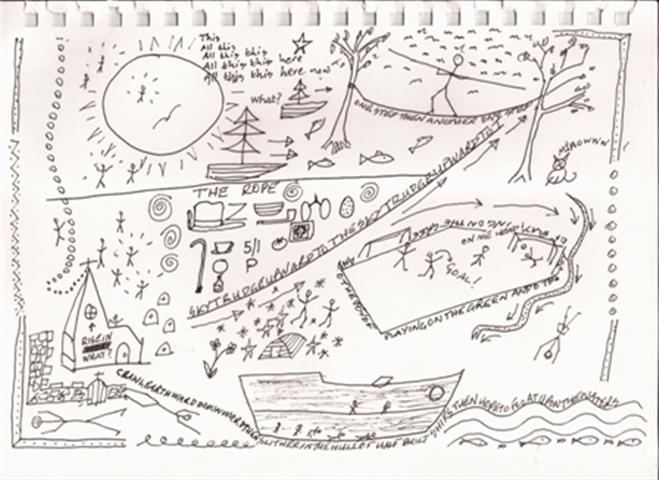

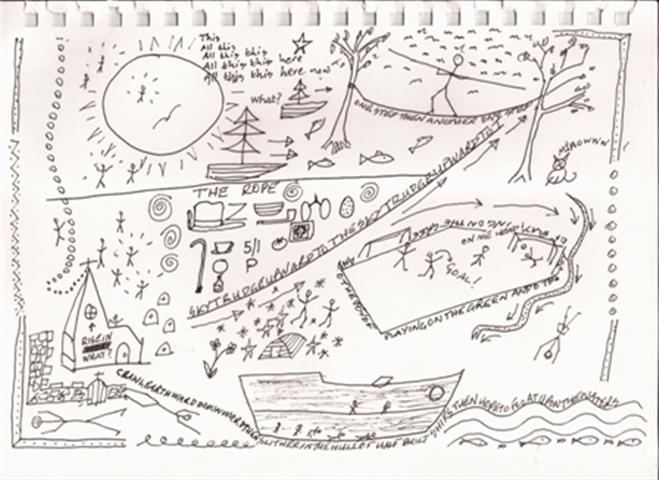

You can plan a story to death, but it kills it off. If you begin to write something interesting, it takes on its own life. It grows like a living thing. Mina knows that. When everyone has to sit down and write an essay on the same subject in the same number of minutes, she thinks, "Would William Blake have subjected himself to this? Shakespeare?" A page of nonsense might be their response--which was lovely to write. She's writing something well, inside the strictures of this test. That was an act of courage as well. The nature of creativity and the nature of schooling will always be at odds with each other, they're bound to be.

Is it true that you initially resisted the idea of writing something for the 10th anniversary edition of Skellig?

When Beverly Horowitz said, "How about doing something a little extra for the 10th anniversary?" I thought, "Oh no!" Then I thought, "Aha! I'll do a few pages of Mina's notebook." As soon as I put down the first notes, it was obvious there was a whole book waiting to be written. Mina is obviously drawn from something in my mind and the way I write. She's focused on the real world but showing the miraculousness of it, and though terrible things happen to us, we can transcend them through joyful means.

photo: Sara Jane Palmer

David Almond's books reveal the magical moments waiting to be discovered in the course of everyday human experience.

David Almond's books reveal the magical moments waiting to be discovered in the course of everyday human experience.

In its citation for David Almond's 2010 Hans Christian Andersen Award, the jury noted his "unique voice as a creator of magic realism for children." He balks at the idea of trying to categorize his work--though he acknowledges the influence of writers like García Márquez, Borges and Calvino. But for him, "the primary thing about my books is the realism. They're straightforward, ordinary people in ordinary places, but inside them are extraordinary things." Almond never planned to return to Skellig or its characters. But when editor Beverly Horowitz called him to ask if he could add a little something for the 10th anniversary edition, Mina was waiting for him.

In its citation for David Almond's 2010 Hans Christian Andersen Award, the jury noted his "unique voice as a creator of magic realism for children." He balks at the idea of trying to categorize his work--though he acknowledges the influence of writers like García Márquez, Borges and Calvino. But for him, "the primary thing about my books is the realism. They're straightforward, ordinary people in ordinary places, but inside them are extraordinary things." Almond never planned to return to Skellig or its characters. But when editor Beverly Horowitz called him to ask if he could add a little something for the 10th anniversary edition, Mina was waiting for him. Did you find that you revisited Skellig to jumpstart Mina's story? Or was her story so strong in your mind that you didn't have to go back?

Did you find that you revisited Skellig to jumpstart Mina's story? Or was her story so strong in your mind that you didn't have to go back? Mina often cites this quote from William Blake: "How can a bird that is born for joy/ sit in a cage and sing?" It's in Skellig, too. You create layers of meaning behind this phrase that reverberate within this book and also in Skellig.

Mina often cites this quote from William Blake: "How can a bird that is born for joy/ sit in a cage and sing?" It's in Skellig, too. You create layers of meaning behind this phrase that reverberate within this book and also in Skellig. "It's always hard to go back to someone who's completed a seemingly perfect book, right?" said Beverly Horowitz, v-p and publisher of Delacorte Press. That's what Skellig was, the perfect book. Even now, David Almond says that whatever book he goes to schools to talk about, Skellig is the one kids want to discuss. But for the 10th anniversary of the U.S. edition in 2009, Horowitz and her colleagues had a big discussion, and she left thinking, "I can't think of anything to do except to have a little more about these characters." She called him on the phone before she could stop herself and reached him right away.

"It's always hard to go back to someone who's completed a seemingly perfect book, right?" said Beverly Horowitz, v-p and publisher of Delacorte Press. That's what Skellig was, the perfect book. Even now, David Almond says that whatever book he goes to schools to talk about, Skellig is the one kids want to discuss. But for the 10th anniversary of the U.S. edition in 2009, Horowitz and her colleagues had a big discussion, and she left thinking, "I can't think of anything to do except to have a little more about these characters." She called him on the phone before she could stop herself and reached him right away. The good news for young readers is how Mina's journal entries model creativity and freedom. "The idea that I don't have to write in a linear manner, that I'm going to find things in daily life to write about. Those are things that can inspire a kid," Horowitz said. "And that's what he's helping kids to see--you can be creative on your own terms." One of the reasons Horowitz believes Almond's work has enduring appeal for both children and adults is the honesty in his characters' relationships. Mina and her mother have both experienced a tremendous loss--Mina's lost her father, her mother has lost her husband. "A book has the power to rip away the protection," said Horowitz. "As much as we all want to protect children, they can spot a fake from a mile away. Even when you can't fix the situation, instead of making it a fake fix, you can make it a more realistic, honest and straightforward response."

The good news for young readers is how Mina's journal entries model creativity and freedom. "The idea that I don't have to write in a linear manner, that I'm going to find things in daily life to write about. Those are things that can inspire a kid," Horowitz said. "And that's what he's helping kids to see--you can be creative on your own terms." One of the reasons Horowitz believes Almond's work has enduring appeal for both children and adults is the honesty in his characters' relationships. Mina and her mother have both experienced a tremendous loss--Mina's lost her father, her mother has lost her husband. "A book has the power to rip away the protection," said Horowitz. "As much as we all want to protect children, they can spot a fake from a mile away. Even when you can't fix the situation, instead of making it a fake fix, you can make it a more realistic, honest and straightforward response." On your nightstand now:

On your nightstand now: