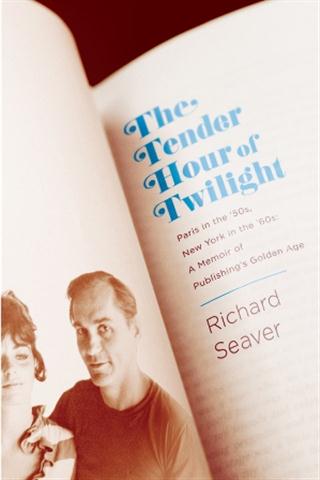

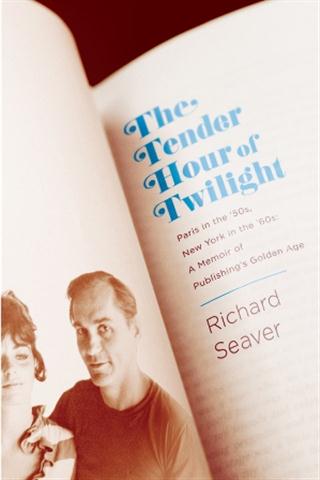

In his introduction to The Tender Hour of Twilight, James Salter describes Richard Seaver as "a man of character, charm, and a New England-bred integrity." He was a publisher who cared about fine writing, willing to promote an author even when it might get his press in trouble. He had been writing this lively, in-depth memoir for many years, but died before it was published--leaving his wife, Jeannette, to sort through thousands of manuscript pages to bring us this important memoir.

In his introduction to The Tender Hour of Twilight, James Salter describes Richard Seaver as "a man of character, charm, and a New England-bred integrity." He was a publisher who cared about fine writing, willing to promote an author even when it might get his press in trouble. He had been writing this lively, in-depth memoir for many years, but died before it was published--leaving his wife, Jeannette, to sort through thousands of manuscript pages to bring us this important memoir.

Seaver's story begins in 1950s France, a world with plenty to offer a bright, energetic young man who loved literature--and life. Using his Fulbright scholarship to work on his dissertation at the Sorbonne, he met and fell in love with Jeannette, wrote an important essay on the work of Samuel Beckett and co-founded a literary journal, Merlin, that published several writers then largely unknown to American readers, many of whom he was translating himself. And he still had time to hobnob with the likes of Orson Welles and Brendan Behan. The conversational and entertaining memoir is crammed full of details, but one can't help but be carried along by Seaver's enthusiasm as he writes with so much joy about one exciting literary encounter after another.

Seaver also first met Barney Rosset in France; later, when he arrived in New York City, he fit in perfectly at Rosset's Grove Press, where he was reunited with Beckett, helping to shepherd his greatest works into print. Things were never quiet at Grove: Naked Lunch, then City of Night, then Last Exit to Brooklyn, closely followed by The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Story of O (which Seaver translated himself, under a pseudonym). All these books faced hard publication battles, taking a financial toll on the company, but Grove didn't do P&L statements. Luckily, Eric Berne came along, promising that his guidebook to transactional psychology, Games People Play, would sell hundreds of thousands of copies. It did, and more after that, and became the book "that saved our skin," so successful its title entered the popular lexicon.

Eventually, after new financial problems and conflicts with Rosset, Seaver felt he had to leave. He describes their last meeting affectionately; they parted as friends, with a "hug as hearty as any I'd ever had." The memoir ends here, in 1971: afterward, Seaver went to Viking, from there to Holt, Rinehart, and Winston and then his own Arcade imprint. He died in 2009 at the age of 82, still publishing the dynamic new voices in literature he loved. --Tom Lavoie, former publisher

Shelf Talker: A fascinating inside look at modern publishing from one of its most esteemed and respected members--so conversational it's like drinking white wine with Seaver in a small French café.

"You are no more likely to discover a book buried in the stacks of a bookstore than you are to find it perusing Amazon's webpages. But you are more likely to discover something different, because there is a unique group of people reading, selecting, and promoting titles at each store.... It's not about whether one store makes better choices than another in regard to what it stocks and displays on its shelves; it's about the variety of choices. ... In almost all other industries, we value experts and their opinions, and often reward their experience monetarily.... It is alarming that we don't place that same value on professionals working in the book business... Anyone who claims to value literary culture should be advocating for more: more books, more readers, more access, more services, more exposure, more formats. More choices."

"You are no more likely to discover a book buried in the stacks of a bookstore than you are to find it perusing Amazon's webpages. But you are more likely to discover something different, because there is a unique group of people reading, selecting, and promoting titles at each store.... It's not about whether one store makes better choices than another in regard to what it stocks and displays on its shelves; it's about the variety of choices. ... In almost all other industries, we value experts and their opinions, and often reward their experience monetarily.... It is alarming that we don't place that same value on professionals working in the book business... Anyone who claims to value literary culture should be advocating for more: more books, more readers, more access, more services, more exposure, more formats. More choices."

SHELFAWARENESS.0213.S4.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

In

In SHELFAWARENESS.0213.T3.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

On the occasion of the death of Kim Jong-Il, head of North Korea (and just in time for the holidays), Sarah Weinman offers a list of "novels and nonfiction works that help further understand this oppressive dictatorship that was often stranger than satire." See the list on her blog,

On the occasion of the death of Kim Jong-Il, head of North Korea (and just in time for the holidays), Sarah Weinman offers a list of "novels and nonfiction works that help further understand this oppressive dictatorship that was often stranger than satire." See the list on her blog,  Author and bookseller

Author and bookseller

Hyperion Books held its annual holiday party last Thursday, at which this year's inaugural Holiday Bake Off was judged by Gail Simmons, host of Bravo's Top Chef: Just Desserts and author of the upcoming memoir, Talking with My Mouth Full; blogger Lisa Fain, author of The Homesick Texan; and Edward Ash-Milby, Barnes & Noble's cookbook buyer. Here (l.) is sales director Sarah Rucker, judged the top chef in the savory category for her Pizza Rustica ("a revelation"), with Ash-Milby and Fain.

Hyperion Books held its annual holiday party last Thursday, at which this year's inaugural Holiday Bake Off was judged by Gail Simmons, host of Bravo's Top Chef: Just Desserts and author of the upcoming memoir, Talking with My Mouth Full; blogger Lisa Fain, author of The Homesick Texan; and Edward Ash-Milby, Barnes & Noble's cookbook buyer. Here (l.) is sales director Sarah Rucker, judged the top chef in the savory category for her Pizza Rustica ("a revelation"), with Ash-Milby and Fain. On Friday, Nicholas Sparks told viewers of CBS's Early Show that his novel

On Friday, Nicholas Sparks told viewers of CBS's Early Show that his novel  CBS Films released a trailer for

CBS Films released a trailer for  In his introduction to The Tender Hour of Twilight, James Salter describes Richard Seaver as "a man of character, charm, and a New England-bred integrity." He was a publisher who cared about fine writing, willing to promote an author even when it might get his press in trouble. He had been writing this lively, in-depth memoir for many years, but died before it was published--leaving his wife, Jeannette, to sort through thousands of manuscript pages to bring us this important memoir.

In his introduction to The Tender Hour of Twilight, James Salter describes Richard Seaver as "a man of character, charm, and a New England-bred integrity." He was a publisher who cared about fine writing, willing to promote an author even when it might get his press in trouble. He had been writing this lively, in-depth memoir for many years, but died before it was published--leaving his wife, Jeannette, to sort through thousands of manuscript pages to bring us this important memoir.