Litquake, the "largest indie literary festival in the West" since 1999, and the Grotto, a community of artistic peers who came together in 1996, have grown up together. Recently, they combined forces to present an evening called "Regreturature," in which published writers read works they wrote much earlier in their careers--or before they had careers at all. The evening was one of the periodic events Litquake hosts throughout the year as fundraisers for its main, week-long series held in the fall.

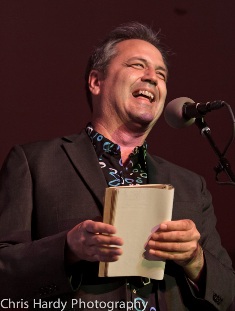

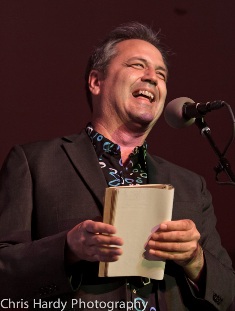

Litquake cofounder Jack Boulware served as master of ceremonies, welcoming the sold-out crowd of about 250 to a Potrero Hill neighborhood meeting place that was equal parts gymnasium and dance hall (with a full bar, of course).

Litquake cofounder Jack Boulware served as master of ceremonies, welcoming the sold-out crowd of about 250 to a Potrero Hill neighborhood meeting place that was equal parts gymnasium and dance hall (with a full bar, of course).

Boulware, author of Gimme Something Better:The Profound Progressive and Occasionally Pointless History of Bay Area Punk Rock from Dead Kennedys to Green Day (Penguin, 2009), dove in first, sharing some of his journal writings as a sophomore at the University of Oregon in 1980. "Will I ever join the mainstream of society?" the young Boulware pondered on the page. "Why does money create such a hassle?" After calling to task the "trendy predictables" on campus, the older Boulware commented: "Whoever wrote this would fucking hate me now."

Mary Roach, bestselling author of Stiff, Spook, Bonk and, most recently, Packing for Mars (Norton), said that her first paid job as a writer was working in public information for the ASPCA. Mostly she followed a script answering animal questions and wrote the occasional "Pet Tips" column for the San Francisco Examiner--sans byline, much to her chagrin at the time.

Taking the stage grasping a yellowed newspaper column, Roach read from "Guppy Love," a column that asked simply, "And why not guppies?" Sure, they are usually bought to feed other fish, she continued, but "their demands are few," Roach continued. With little effort, they'll produce "50 or so" offspring or "guplets"--a term Roach proudly got past her editor. And never mind that they eat their young, which is all part of the "guppy way of life." Drawing in on her 600-word limit, Roach wrapped things up quickly with: "Let's hear it for guppies."

Long before globetrotting writer and photographer Jeff Greenwald penned such books as Shopping for Buddhas and Snake Lake, he wrote poetry. His employer even published his first volume of verse, Amber Fortress: Family Pharmacy Poetry Series Vol. One. He said there were two things to note about the book: there was no Vol. Two, and he discovered a used copy in the bins at Green Apple Books signed, "To Mom and Dad with all my love, Jeff Greenwald."

Greenwald could hardly read his verse about "facing the ocean and the seals" without cracking himself up.

Greenwald could hardly read his verse about "facing the ocean and the seals" without cracking himself up.

It was to be a common reaction among the Regreturature readers.

Julia Scott, a San Francisco journalist and broadcaster, recalled her young self's obsession with Tom Stoppard, which culminated in her sitting behind the playwright during a performance of one of this plays. Scott never got to speak to Stoppard, but she wrote in her journal: "It's enough to know that I am living in the same lifetime."

In the second half, Katie Crouch, author of Girls in Trucks and Men and Dogs, shared the journal writings of her nine-year-old self. Writing as if for a time capsule--convinced of her pending fame--young Crouch wrote about playing college with her best friend, unrequited love with a boy named Jake ("I will never love again") and envying a girl named Frances whose mother owned a cool clothing store and who had kissed lots of boys. "I only kissed one and he was related to me," she wrote.

Perhaps the greatest act of bravery that evening came when Heather Donahue, author of the memoir Growgirl (Gotham), star of The Blair Witch Project and guest star on It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, shared her "atomic hairdo" photo before reading a short story she wrote the story at 11. "Coping" tells the tragic tale of BFFs Cara and Kim; Cara dies accidentally and Kim falls in love with her therapist, Jordan. Eventually, Jordan and Kim start a teen counseling center and have a daughter--named Cara.

Perhaps the greatest act of bravery that evening came when Heather Donahue, author of the memoir Growgirl (Gotham), star of The Blair Witch Project and guest star on It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, shared her "atomic hairdo" photo before reading a short story she wrote the story at 11. "Coping" tells the tragic tale of BFFs Cara and Kim; Cara dies accidentally and Kim falls in love with her therapist, Jordan. Eventually, Jordan and Kim start a teen counseling center and have a daughter--named Cara.

Which just goes to show that, at any age, a happy ending goes a long way. --Bridget Kinsella

"And they've invested in supply chain in general, seeing the connection between improving the tech in the reps' hands, the speed of shipment from the warehouse and the development of such capabilities as vendor-managed inventory as worth the effort even in an era when the number of bookstores is getting smaller."

"And they've invested in supply chain in general, seeing the connection between improving the tech in the reps' hands, the speed of shipment from the warehouse and the development of such capabilities as vendor-managed inventory as worth the effort even in an era when the number of bookstores is getting smaller."

New England Independent Booksellers Association president Annie Philbrick of Bank Square Books, Mystic, Conn., wrote, in part, that the association "salutes" Macmillan and Penguin for fighting the Department of Justice lawsuit. "This fight will be long and arduous, not to mention costly, yet, vital to maintain and foster the future of healthy publishing and bookselling. As independent booksellers, we should applaud both the publishers and Apple for standing their ground."

New England Independent Booksellers Association president Annie Philbrick of Bank Square Books, Mystic, Conn., wrote, in part, that the association "salutes" Macmillan and Penguin for fighting the Department of Justice lawsuit. "This fight will be long and arduous, not to mention costly, yet, vital to maintain and foster the future of healthy publishing and bookselling. As independent booksellers, we should applaud both the publishers and Apple for standing their ground." New Atlantic Independent Booksellers Association president Lucy Kogler of Talking Leaves, Buffalo, N.Y., discussed a letter about the suit to authors, illustrators and agents from Macmillan CEO John Sargent, writing, "We, independent booksellers and independent thinkers, applaud John Sargent for his bravery; for his intelligence in recognizing the larger issues of Amazon's monopolistic bullying (including a judiciary that recognizes corporations as people); for his honesty--admitting his agonizing over the issue two years ago; and for his solitary standing. He is not a bystander, nor just a witness, but an actor. History is made by such people."

New Atlantic Independent Booksellers Association president Lucy Kogler of Talking Leaves, Buffalo, N.Y., discussed a letter about the suit to authors, illustrators and agents from Macmillan CEO John Sargent, writing, "We, independent booksellers and independent thinkers, applaud John Sargent for his bravery; for his intelligence in recognizing the larger issues of Amazon's monopolistic bullying (including a judiciary that recognizes corporations as people); for his honesty--admitting his agonizing over the issue two years ago; and for his solitary standing. He is not a bystander, nor just a witness, but an actor. History is made by such people." The long wait is over for muggles worldwide. On Saturday morning at 8 a.m. BST,

The long wait is over for muggles worldwide. On Saturday morning at 8 a.m. BST,  "We are willing to do this because I think it will grow our sales and the authors' sales," said Donald Katz, Audible's CEO. "The fact is people buy a Neil Gaiman, not a HarperCollins or a Simon & Schuster, so it is for us to connect with the writers and hopefully wake them up to what they can do. If it works, it can become a channel of membership and sales."

"We are willing to do this because I think it will grow our sales and the authors' sales," said Donald Katz, Audible's CEO. "The fact is people buy a Neil Gaiman, not a HarperCollins or a Simon & Schuster, so it is for us to connect with the writers and hopefully wake them up to what they can do. If it works, it can become a channel of membership and sales."

Litquake cofounder Jack Boulware served as master of ceremonies, welcoming the sold-out crowd of about 250 to a Potrero Hill neighborhood meeting place that was equal parts gymnasium and dance hall (with a full bar, of course).

Litquake cofounder Jack Boulware served as master of ceremonies, welcoming the sold-out crowd of about 250 to a Potrero Hill neighborhood meeting place that was equal parts gymnasium and dance hall (with a full bar, of course). Greenwald could hardly read his verse about "facing the ocean and the seals" without cracking himself up.

Greenwald could hardly read his verse about "facing the ocean and the seals" without cracking himself up. Perhaps the greatest act of bravery that evening came when Heather Donahue, author of the memoir Growgirl (Gotham), star of The Blair Witch Project and guest star on It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, shared her "atomic hairdo" photo before reading a short story she wrote the story at 11. "Coping" tells the tragic tale of BFFs Cara and Kim; Cara dies accidentally and Kim falls in love with her therapist, Jordan. Eventually, Jordan and Kim start a teen counseling center and have a daughter--named Cara.

Perhaps the greatest act of bravery that evening came when Heather Donahue, author of the memoir Growgirl (Gotham), star of The Blair Witch Project and guest star on It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, shared her "atomic hairdo" photo before reading a short story she wrote the story at 11. "Coping" tells the tragic tale of BFFs Cara and Kim; Cara dies accidentally and Kim falls in love with her therapist, Jordan. Eventually, Jordan and Kim start a teen counseling center and have a daughter--named Cara. On Facebook,

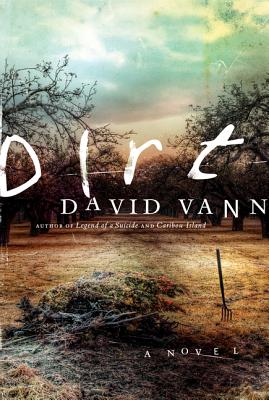

On Facebook,  David Vann's debut, Caribou Island, was no literary accident. That beautifully dark novel was both a fully realized tale and a portent of things to come. Vann has experienced both suicide and murder in his immediate family and has said that writing saved him from the pervasive sense of doom that followed him for many years. It is clear he is still exploring vestiges of that darkness and his understanding of what it can do to families. The arrival of Dirt is testament to these truths.

David Vann's debut, Caribou Island, was no literary accident. That beautifully dark novel was both a fully realized tale and a portent of things to come. Vann has experienced both suicide and murder in his immediate family and has said that writing saved him from the pervasive sense of doom that followed him for many years. It is clear he is still exploring vestiges of that darkness and his understanding of what it can do to families. The arrival of Dirt is testament to these truths.