John Evans, co-owner of Diesel Books, with three stores in California, opened the annual Editors Buzz panel yesterday by reminding attendees that, as a bookseller, he sees first-hand how books found and championed by editors reach customers every day. "Every year books rise" above the din of the thousands published, books that "change the conversation."

Presenting in alphabetical order of editors ("because booksellers love the alphabet," Evans said), Millicent Bennett started out with an admission: she said that Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness by Susannah Cahalan, a memoir by a New York Post reporter who contacted a disease that robbed her of her sanity and nearly sent her to an institution for life, was the kind of book she wished she had acquired--but didn't. She actually inherited the project when she was pregnant and thinking a lot about the futility of life.

The memoir, to be published by the Free Press in November, tells how Cahalan, then 24--who'd just landed a plum New York newspaper job and met a great guy--wound up strapped to a hospital bed. Her estranged father was camped outside her room, determined, like her boyfriend and others, to hold on to hope that the Susannah they knew was still inside the seemingly crazy person. In a stroke of luck, a new doctor diagnosed Cahalan with an autoimmune disease that had not even been named before 2007, but might now explain some other mental illnesses (autism and schizophrenia among them.)

Bennett admitted she developed "medical student syndrome" while reading the book--imagining similar symptoms in her own life--that were not quelled by the doctor's belief that Cahalan was likely infected by a stranger's sneeze on the subway. "Enjoy the next few days going back and forth from the convention center," joked Bennett.

After that dose of reality, Evans noted, it was good the rest of the books were fiction.

The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry by British actress and playwright Rachel Joyce is about a retired man whose life changes when he receives a note from a distant dying friend. "He thinks, if I do the extraordinary by going to her, she might do the extraordinary and survive," said the book's acquiring editor, Kendra Harpster from Random House.

The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry by British actress and playwright Rachel Joyce is about a retired man whose life changes when he receives a note from a distant dying friend. "He thinks, if I do the extraordinary by going to her, she might do the extraordinary and survive," said the book's acquiring editor, Kendra Harpster from Random House.

At first, Harold's wife is angry and does not understand what she sees as his foolish journey. "It is a love story in reverse," said Harpster. As husband and wife shift further away from each other, and from their day-to-day lives, their thoughts and memories start to converge, bringing them closer together. Inspired when her own father was dying, Joyce began the story as a radio play.

Harpster noted that Joyce's acting background informs her character development. "She thinks about how they are off the page in way that I never thought to ask about as an editor."

Responding to Bennett's comments about germs on the subway, McSweeney's editor Eli Horowitz looked at the panel's shared microphone with horror. "Is this going to be some Hunger Games thing, with four of us slaughtered?" he wondered.

Horowitz remembered well how John Brandon's first novel, Arkansas, arrived at his office in a manila envelope. McSweeney's published the then-unknown author and followed up with his Citrus County to some critical acclaim. "This one is so much better than those other two books that it is not even funny," Horowitz said. "But it is actually funny." Still, it might not sound amusing: A Million Heavens is about a boy piano prodigy languishing in a hospital in New Mexico who becomes the target of a weekly parking lot vigil manned by the unlikely cast of characters, including a girl missing her dead bandmate, a secretly romantic mayor, an orphan on the run and a possibly immortal wolf taking in the whole scene. It is as if Barbara Kingsolver and Denis Johnson were locked in a room to rewrite the movie Ghost--"only good"--promised Horowitz.

Horowitz remembered well how John Brandon's first novel, Arkansas, arrived at his office in a manila envelope. McSweeney's published the then-unknown author and followed up with his Citrus County to some critical acclaim. "This one is so much better than those other two books that it is not even funny," Horowitz said. "But it is actually funny." Still, it might not sound amusing: A Million Heavens is about a boy piano prodigy languishing in a hospital in New Mexico who becomes the target of a weekly parking lot vigil manned by the unlikely cast of characters, including a girl missing her dead bandmate, a secretly romantic mayor, an orphan on the run and a possibly immortal wolf taking in the whole scene. It is as if Barbara Kingsolver and Denis Johnson were locked in a room to rewrite the movie Ghost--"only good"--promised Horowitz.

Trish Todd at Simon & Schuster said she had been about to take vacation time when she brought home a manuscript about the Cambodian genocide; she expected to read only 50 pages. After realizing she had not moved one muscle while reading In the Shadow of the Banyan by Vaddey Ratner, she knew her vacation was not to be.

Trish Todd at Simon & Schuster said she had been about to take vacation time when she brought home a manuscript about the Cambodian genocide; she expected to read only 50 pages. After realizing she had not moved one muscle while reading In the Shadow of the Banyan by Vaddey Ratner, she knew her vacation was not to be.

Talking with an author before you acquire their book can be tricky, Todd explained, but her first conversation with Ratner left the 30-year publishing veteran speechless. "I asked why she wrote it as a novel and not a memoir." The answer: the author wanted to memorialize those she had known as a work of art. In giving us a protagonist who honors her poet father's death by seeing beauty around her, Ratner thinks she has succeeded.

In-house buzz at S&S places this book alongside The Kite Runner, Little Bee and even The Diary of Anne Frank, but Todd shared perhaps the most moving critique, which came from the author's mother: "You always believed the world was good, even though it stole so much from you," Ratner's mother wrote.

"If this was the Hunger Games," said Alexis Washam, editor at Crown's Hogarth imprint, "I would hope one of my characters would take my place, because she'd win hands down." The People of Forever Are Not Afraid, a debut by Shani Boianjiu, is about three girls who graduate from high school in a remote town in Israel and join the Israeli Defense Forces.

"If this was the Hunger Games," said Alexis Washam, editor at Crown's Hogarth imprint, "I would hope one of my characters would take my place, because she'd win hands down." The People of Forever Are Not Afraid, a debut by Shani Boianjiu, is about three girls who graduate from high school in a remote town in Israel and join the Israeli Defense Forces.

Washam acquired the book when Boianjiu, after serving in the IDF, was a senior at Harvard. With a ferocious, electric voice, Washam said Boianjiu captures the surreal reality of girls on the cusp of womanhood--forced into maturity yet still obsessed with pop culture, including Dawson's Creek and Ally McBeal.

"It's Tim O'Brien's What They Carried meets The Mean Girls," said Washam, a tagline she doubted has never been used before.

Rounding out the session was Lauren Wein, who acquired a second novel by Antoine Wilson, titled Panorama City, for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt for September release. "This is a novel that brings you back to your childhood self without losing your adult self," she said. Twenty-eight-year-old Oppen Porter, a self-described "slow absorber" who thinks he is dying, speaks about his life into a cassette tape for his unborn son as he spends 40 days and nights traversing the San Fernando Valley.

Rounding out the session was Lauren Wein, who acquired a second novel by Antoine Wilson, titled Panorama City, for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt for September release. "This is a novel that brings you back to your childhood self without losing your adult self," she said. Twenty-eight-year-old Oppen Porter, a self-described "slow absorber" who thinks he is dying, speaks about his life into a cassette tape for his unborn son as he spends 40 days and nights traversing the San Fernando Valley.

"It's the modern strip-mall version of Odysseus," said Wein. The editor recalled a line from Kafka: "A book should take an axe at the frozen sea within us." The manuscript for Panorama City was, Wein said, more like a "raft, oar and compass all in one," arriving at a time when she felt rudderless. "That's a big embarrassing statement, but it's true," she said. Wein said Wilson wrote Panorama City as he was about to become a father, and that it shows; she read it after coming back to work after maternity leave.

Peter Carey said Panorama City had a goodness "you might have even stopped believing is even possible." Wein described the Iowa Workshop graduate's first book, The Interloper, as edgier.

"As an editor you have to be open to things," said Wein. But with e-books and the contraction of bookselling, she asked, "How do you keep true to yourself and not let all of that in?"

Perhaps simply by getting lost on the page--which is what all of these editors hope readers do with their personal picks of the season. --Bridget Kinsella

"There has never been a more exciting time to be part of the conversation about books and reading than there is now," Jennifer Weiner told the audience during her keynote address to the third annual Book Blogger Conference (the first to be owned and operated by BookExpo America itself rather than as a partnering event). In a free-ranging talk, Weiner said that Oprah Winfrey's original book club had all the qualities that would come to be associated with book blogs ("Oprah didn't sound like a book critic; she sounded like a friend") and Weiner discussed how she had used social media to combat the sexism and discrimination she sees in contemporary publishing and literary media--beginning with an offer to send a signed copy of one of her books to readers who sent proof that they'd purchased Sarah Pekkanen's debut novel, The Opposite of Me. After giving away more than 400 books on that project, she continues to make similar offers whenever she finds a book she's passionate about.

"There has never been a more exciting time to be part of the conversation about books and reading than there is now," Jennifer Weiner told the audience during her keynote address to the third annual Book Blogger Conference (the first to be owned and operated by BookExpo America itself rather than as a partnering event). In a free-ranging talk, Weiner said that Oprah Winfrey's original book club had all the qualities that would come to be associated with book blogs ("Oprah didn't sound like a book critic; she sounded like a friend") and Weiner discussed how she had used social media to combat the sexism and discrimination she sees in contemporary publishing and literary media--beginning with an offer to send a signed copy of one of her books to readers who sent proof that they'd purchased Sarah Pekkanen's debut novel, The Opposite of Me. After giving away more than 400 books on that project, she continues to make similar offers whenever she finds a book she's passionate about.

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.S1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

"These are times of real opportunities," said Becky Anderson, ABA president and owner of Anderson's Bookshops in Naperville and Downers Grove, Ill. She was speaking to a large audience at yesterday's "Why Indies Matter" event featuring broadcaster and author Lynn Sherr interviewing author Richard Russo. Anderson noted Russo's long and positive relationship with independent bookstores, calling him "an author we have known and loved and whose books we have loved handselling."

"These are times of real opportunities," said Becky Anderson, ABA president and owner of Anderson's Bookshops in Naperville and Downers Grove, Ill. She was speaking to a large audience at yesterday's "Why Indies Matter" event featuring broadcaster and author Lynn Sherr interviewing author Richard Russo. Anderson noted Russo's long and positive relationship with independent bookstores, calling him "an author we have known and loved and whose books we have loved handselling."

The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry by British actress and playwright Rachel Joyce is about a retired man whose life changes when he receives a note from a distant dying friend. "He thinks, if I do the extraordinary by going to her, she might do the extraordinary and survive," said the book's acquiring editor, Kendra Harpster from Random House.

The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry by British actress and playwright Rachel Joyce is about a retired man whose life changes when he receives a note from a distant dying friend. "He thinks, if I do the extraordinary by going to her, she might do the extraordinary and survive," said the book's acquiring editor, Kendra Harpster from Random House. Horowitz remembered well how John Brandon's first novel, Arkansas, arrived at his office in a manila envelope. McSweeney's published the then-unknown author and followed up with his Citrus County to some critical acclaim. "This one is so much better than those other two books that it is not even funny," Horowitz said. "But it is actually funny." Still, it might not sound amusing: A Million Heavens is about a boy piano prodigy languishing in a hospital in New Mexico who becomes the target of a weekly parking lot vigil manned by the unlikely cast of characters, including a girl missing her dead bandmate, a secretly romantic mayor, an orphan on the run and a possibly immortal wolf taking in the whole scene. It is as if Barbara Kingsolver and Denis Johnson were locked in a room to rewrite the movie Ghost--"only good"--promised Horowitz.

Horowitz remembered well how John Brandon's first novel, Arkansas, arrived at his office in a manila envelope. McSweeney's published the then-unknown author and followed up with his Citrus County to some critical acclaim. "This one is so much better than those other two books that it is not even funny," Horowitz said. "But it is actually funny." Still, it might not sound amusing: A Million Heavens is about a boy piano prodigy languishing in a hospital in New Mexico who becomes the target of a weekly parking lot vigil manned by the unlikely cast of characters, including a girl missing her dead bandmate, a secretly romantic mayor, an orphan on the run and a possibly immortal wolf taking in the whole scene. It is as if Barbara Kingsolver and Denis Johnson were locked in a room to rewrite the movie Ghost--"only good"--promised Horowitz. Trish Todd at Simon & Schuster said she had been about to take vacation time when she brought home a manuscript about the Cambodian genocide; she expected to read only 50 pages. After realizing she had not moved one muscle while reading In the Shadow of the Banyan by Vaddey Ratner, she knew her vacation was not to be.

Trish Todd at Simon & Schuster said she had been about to take vacation time when she brought home a manuscript about the Cambodian genocide; she expected to read only 50 pages. After realizing she had not moved one muscle while reading In the Shadow of the Banyan by Vaddey Ratner, she knew her vacation was not to be. "If this was the Hunger Games," said Alexis Washam, editor at Crown's Hogarth imprint, "I would hope one of my characters would take my place, because she'd win hands down." The People of Forever Are Not Afraid, a debut by Shani Boianjiu, is about three girls who graduate from high school in a remote town in Israel and join the Israeli Defense Forces.

"If this was the Hunger Games," said Alexis Washam, editor at Crown's Hogarth imprint, "I would hope one of my characters would take my place, because she'd win hands down." The People of Forever Are Not Afraid, a debut by Shani Boianjiu, is about three girls who graduate from high school in a remote town in Israel and join the Israeli Defense Forces. Rounding out the session was Lauren Wein, who acquired a second novel by Antoine Wilson, titled Panorama City, for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt for September release. "This is a novel that brings you back to your childhood self without losing your adult self," she said. Twenty-eight-year-old Oppen Porter, a self-described "slow absorber" who thinks he is dying, speaks about his life into a cassette tape for his unborn son as he spends 40 days and nights traversing the San Fernando Valley.

Rounding out the session was Lauren Wein, who acquired a second novel by Antoine Wilson, titled Panorama City, for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt for September release. "This is a novel that brings you back to your childhood self without losing your adult self," she said. Twenty-eight-year-old Oppen Porter, a self-described "slow absorber" who thinks he is dying, speaks about his life into a cassette tape for his unborn son as he spends 40 days and nights traversing the San Fernando Valley.

Walter Dean Myers, the National Ambassador for Young People's Literature, kicked off School Library Journal's Day of Dialog. "Language Poverty" is how he described the growing reading gap between kids in homes with unemployed or underemployed parents and kids whose parents use the language of the workplace. "We must change the educational system to deal with 'unequal scholars,' " he said, arguing that a major part of the problem is the "silence" around the topic. The two crises in this country, he suggested, are "a growing illiteracy rate and a high incarceration rate." We have to either "take the leap of faith, he urged, or accept the consequences of the world illiteracy will introduce."

Walter Dean Myers, the National Ambassador for Young People's Literature, kicked off School Library Journal's Day of Dialog. "Language Poverty" is how he described the growing reading gap between kids in homes with unemployed or underemployed parents and kids whose parents use the language of the workplace. "We must change the educational system to deal with 'unequal scholars,' " he said, arguing that a major part of the problem is the "silence" around the topic. The two crises in this country, he suggested, are "a growing illiteracy rate and a high incarceration rate." We have to either "take the leap of faith, he urged, or accept the consequences of the world illiteracy will introduce."

In the early 1900s, the western area around the Meatpacking District and Chelsea was the largest industrial section of Manhattan, and a set of elevated tracks were created to move freight off the cluttered streets below. As New York City evolved, the rails eventually became obsolete, and in 1999 a plan was made to convert the scarring strands of metal into an unusual elevated public green space. On June 9, 2009, part one of what quickly became the city's most beloved urban renewal project opened. Full of blooming flowers and Kelly-green trees, it's been one of New York's star attractions ever since. Here is information and some tips about the High Line from Lonely Planet.

In the early 1900s, the western area around the Meatpacking District and Chelsea was the largest industrial section of Manhattan, and a set of elevated tracks were created to move freight off the cluttered streets below. As New York City evolved, the rails eventually became obsolete, and in 1999 a plan was made to convert the scarring strands of metal into an unusual elevated public green space. On June 9, 2009, part one of what quickly became the city's most beloved urban renewal project opened. Full of blooming flowers and Kelly-green trees, it's been one of New York's star attractions ever since. Here is information and some tips about the High Line from Lonely Planet.

As you walk along the High Line, you'll find staffers wearing shirts with the signature double-H logo who can point you in the right direction or offer you additional information about the converted rails. There are also myriad staffers behind the scenes organizing public art exhibitions and activity sessions for family and friends. Group tours for children can be organized on a variety of topics from the plant life of the high-rise park to the area's history.

As you walk along the High Line, you'll find staffers wearing shirts with the signature double-H logo who can point you in the right direction or offer you additional information about the converted rails. There are also myriad staffers behind the scenes organizing public art exhibitions and activity sessions for family and friends. Group tours for children can be organized on a variety of topics from the plant life of the high-rise park to the area's history.

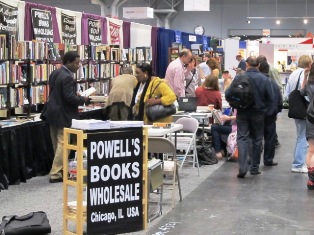

My Bookstore: Writers Celebrate Their Favorite Places to Browse, Read, and Shop, edited by Ronald Rice with illustrations by Leif Parsons, will be published by Black Dog & Leventhal November 13. Bookselling This Week reported that the book "features essays from more than 75 authors who pay tribute to their favorite bookstores and booksellers." Richard Russo wrote the introduction.

My Bookstore: Writers Celebrate Their Favorite Places to Browse, Read, and Shop, edited by Ronald Rice with illustrations by Leif Parsons, will be published by Black Dog & Leventhal November 13. Bookselling This Week reported that the book "features essays from more than 75 authors who pay tribute to their favorite bookstores and booksellers." Richard Russo wrote the introduction.

Set in Makarska, a small coastal city in Croatia, in the early 1960s, Every Day, Every Hour begins when five-year-old Luka, smitten by a new classmate, Dora, faints in excitement. She wakes him with a kiss. Dora and Luka become inseparable over the next few years, wandering the shores of their town as Luka learns to paint, until one September day, when Dora must move with her parents to Paris, leaving Luka behind in Croatia. After 16 years apart, Dora and Luka meet again by chance in Paris. Luka is now an artist, and Dora an actress. They spend three wonderful months together, which they suppose is the beginning of a whole life together. First, Luka needs to settle a few things back in Croatia. He returns to Makarska with the promise of returning to Dora as quickly as possible. Luka is not heard from again.

Set in Makarska, a small coastal city in Croatia, in the early 1960s, Every Day, Every Hour begins when five-year-old Luka, smitten by a new classmate, Dora, faints in excitement. She wakes him with a kiss. Dora and Luka become inseparable over the next few years, wandering the shores of their town as Luka learns to paint, until one September day, when Dora must move with her parents to Paris, leaving Luka behind in Croatia. After 16 years apart, Dora and Luka meet again by chance in Paris. Luka is now an artist, and Dora an actress. They spend three wonderful months together, which they suppose is the beginning of a whole life together. First, Luka needs to settle a few things back in Croatia. He returns to Makarska with the promise of returning to Dora as quickly as possible. Luka is not heard from again.  In The World Without You, Joshua Henkin (Matrimony) covers the perilous and rocky terrain of the Frankels, who gather at their summer home in the Berkshires on the Fourth of July. Leo Frankel, an investigative journalist and a fearless adventurer, was killed in Iraq one year ago and this mostly nonobservant Jewish family is now ready to unveil his tombstone.

In The World Without You, Joshua Henkin (Matrimony) covers the perilous and rocky terrain of the Frankels, who gather at their summer home in the Berkshires on the Fourth of July. Leo Frankel, an investigative journalist and a fearless adventurer, was killed in Iraq one year ago and this mostly nonobservant Jewish family is now ready to unveil his tombstone.