Wi2026: 'Shifts in the Tide'

In a panel discussion at Winter Institute 2026 Monday afternoon, American Booksellers Association CEO Allison Hill identified two "shifts in the tide" that could drastically change the industry in the coming years: the decline in reading and the proliferation of artificial intelligence.

In a panel discussion at Winter Institute 2026 Monday afternoon, American Booksellers Association CEO Allison Hill identified two "shifts in the tide" that could drastically change the industry in the coming years: the decline in reading and the proliferation of artificial intelligence.

On hand to talk about the decline in reading were Nic Bottomley, co-owner of Mr. B's Emporium of Reading Delights in Bath, England, and Brien Lopez, manager of Children's Book World in Los Angeles, Calif. Then Lopez, Bookshop.org CEO Andy Hunter, and ABA director of IndieCommerce Phil Davies discussed AI.

Bottomley described the National Year of Reading, a literacy initiative designed to combat what in the U.K. is called the reading crisis. The initiative has government support and is designed to get everyone reading, though Bottomley noted there are three particularly crucial segments: getting parents reading to children between the ages of 1 and 5; getting teenage boys reading; and getting books into low-income households.

|

|

| From left: Allison Hill, Phil Davies, Andy Hunter, and Brien Lopez | |

One early lesson from the campaign is the value of rebranding and reframing--instead of talking about a reading crisis, the U.K. is now celebrating a national year of reading. The campaign has also served as a reminder of the critical work that bookshops and libraries already do and has helped remind the entire ecosystem "how vital they are."

Lopez said the core of the bookselling business is "sharing the joy of reading," and while booksellers are doing "so many things right," there are areas for improvement. He encouraged booksellers to think about how they curate children's titles: Are they organized to make it easier for staff members to shelve, or for children to find what excites them? Kids, he pointed out, "are not going to look by an author's last name."

More broadly, adults create plenty of "roadblocks" that are "not conducive to a child loving reading." Books get labeled as "good books" or "bad books," with graphic novels often included in the latter category, and Lopez said he's seen so many parents try to steer their children away from graphic novels. He has advised parents "over and over again" to let their children read what they like and start their reading lives in a "joyful place." A child who loves graphic novels could easily start reading chapter books, but a child discouraged from reading graphic novels probably won't suddenly start reading chapter books of their own volition.

Bottomley agreed, saying he'd "rather see bookshops come from a place of welcome and warmth" than dictate what customers should or should not read. He said he thinks of the shop as a "playground for books" and believes the right book "is the one the customer is in the mood for." He was skeptical of bookshops that have things like no-cellphones rules, and encouraged booksellers to think hard about "how to make our shops the most welcoming spaces they can be." The best way for booksellers to achieve their missions, he said, "is to still be in business."

'Forced into the Future'

After Hunter and Davies took the stage to join the conversation about AI, Hunter described a chaotic, unclear situation, with the tech industry and the current administration rushing to build AI infrastructure as fast as they can, burning through huge amounts of both money and fossil fuels. In the book industry, it's already taking work from translators and illustrators, and the market is being flooded with low-quality titles. Society is being "forced into the future" at an incredibly rapid speed, and the people driving it all "don't even know what's going to happen."

Though the AI situation is altogether "not looking great," Hunter continued, there are still reasons to be engaged. If AI is the battlefield of the future, he said, it would be a mistake to disengage entirely and "cede it to people who don't share our values." He suggested the industry look into ways that AI can help business, mentioning that AI tools might help Bookshop's small engineering team develop new features in less time.

The ongoing deluge of AI slop also affords the industry the opportunity to "turn it around" by emphasizing the value and importance of human work. There are some nascent initiatives in the works to create "certified human" badges and labels, and in general, as "everything gets sh*ttier," people will look to sources of integrity and quality. Booksellers can be those sources, Hunter said.

Davies agreed that booksellers shouldn't discard AI entirely. The technology "won't go away," and booksellers could have the chance to help "remake" AI in the "image you want." He said IndieCommerce is looking at "minimalist" ways to utilize AI, with one example being using AI tools to help stop AI titles from flooding IndieCommerce feeds.

Lopez urged publishers who are acquiring books from self-published authors to do their "due diligence" and make sure the books were not made with AI. Sometimes it seems that publishers are "not even looking at the flash drives" before publishing, and booksellers are seeing the results in-store. At the same time, he's finding more and more children's books without an author or illustrator name on them; looking inside those titles, it's clear what's going on. "It's already here," he said. --Alex Mutter

Booksellers streamed into the Galley Room following its opening on Tuesday morning.

Booksellers streamed into the Galley Room following its opening on Tuesday morning. The panel at the Learning from Alternative & Adaptive Models educational session at the Independent Publishers Caucus's Indie Press Summit: (from l.) moderator Andrea Fleck Nisbet, Independent Book Publishers Association; Madeleine McIntosh, Authors Equity; Angela Engel, the Collective Book Studio; and Chris Gruener, Stable Book Co.

The panel at the Learning from Alternative & Adaptive Models educational session at the Independent Publishers Caucus's Indie Press Summit: (from l.) moderator Andrea Fleck Nisbet, Independent Book Publishers Association; Madeleine McIntosh, Authors Equity; Angela Engel, the Collective Book Studio; and Chris Gruener, Stable Book Co. At the Vendor Showcase, HarperCollins staff celebrated their American Classics series, launching in May.

At the Vendor Showcase, HarperCollins staff celebrated their American Classics series, launching in May. The keynote conversation on the state of the industry at the Independent Publishers Caucus's Indie Press Summit featured (from l.) CJ Alberts of Bindery Books and Sunny's bookstore, Yuma, Ariz.; Christie Henry of Princeton University Press; Doug Seibold of Agate Publishing; moderator Patrick Hughes of Pluto Press; Peggy Burns, Drawn & Quarterly; and Andy Hunter of Bookshop.org.

The keynote conversation on the state of the industry at the Independent Publishers Caucus's Indie Press Summit featured (from l.) CJ Alberts of Bindery Books and Sunny's bookstore, Yuma, Ariz.; Christie Henry of Princeton University Press; Doug Seibold of Agate Publishing; moderator Patrick Hughes of Pluto Press; Peggy Burns, Drawn & Quarterly; and Andy Hunter of Bookshop.org.

A bird's-eye view of the Wednesday evening Author Reception.

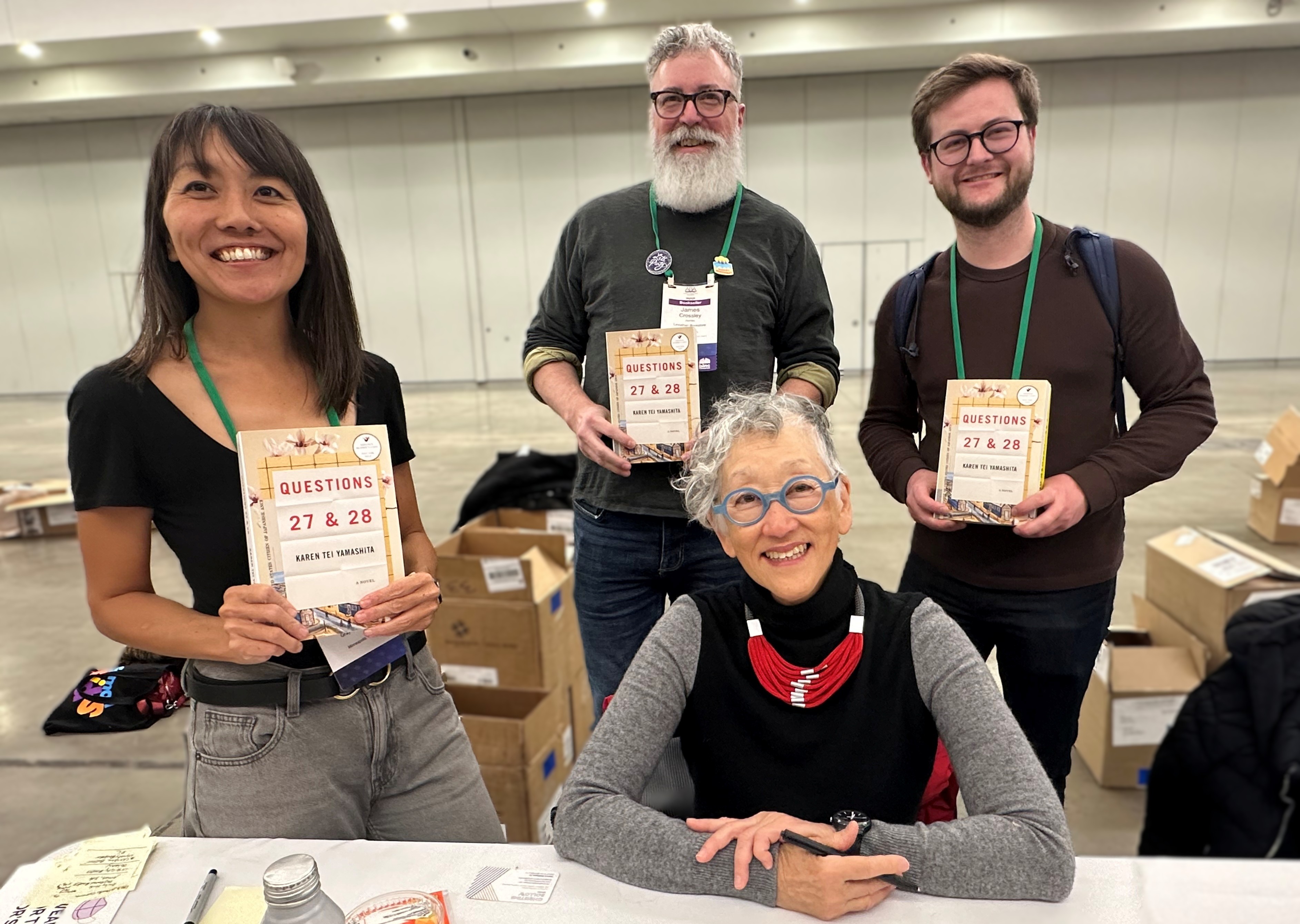

A bird's-eye view of the Wednesday evening Author Reception. Karen Tei Yamashita, author of Questions 27 & 28 (Graywolf Press, April 28), with (standing, from l.) Yuka Igarashi of Graywolf; James Crossley, Leviathan Bookstore, St. Louis, Mo.; and Spencer Ruchti, Third Place Books, Seattle, Wash.

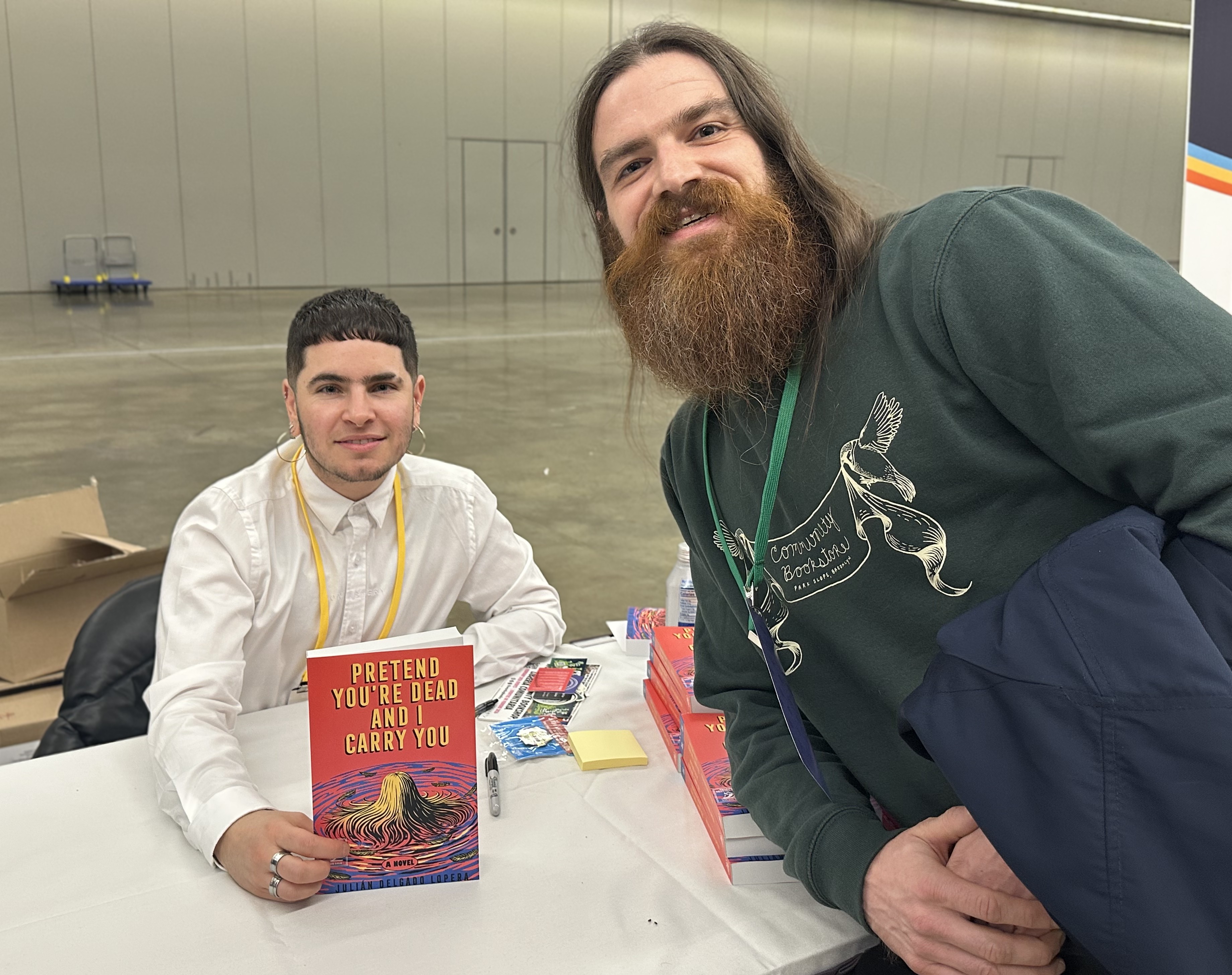

Karen Tei Yamashita, author of Questions 27 & 28 (Graywolf Press, April 28), with (standing, from l.) Yuka Igarashi of Graywolf; James Crossley, Leviathan Bookstore, St. Louis, Mo.; and Spencer Ruchti, Third Place Books, Seattle, Wash.  Julián Delgado Lopera

Julián Delgado Lopera

As part of its Lunch & Learn series, the Book Industry Study Group is hosting a webinar this coming Tuesday, March 3, noon-1 p.m. Eastern, on how booksellers view the supply chain. Speakers are Roxanne J. Coady, founder and owner of

As part of its Lunch & Learn series, the Book Industry Study Group is hosting a webinar this coming Tuesday, March 3, noon-1 p.m. Eastern, on how booksellers view the supply chain. Speakers are Roxanne J. Coady, founder and owner of

Posted on Instagram by

Posted on Instagram by

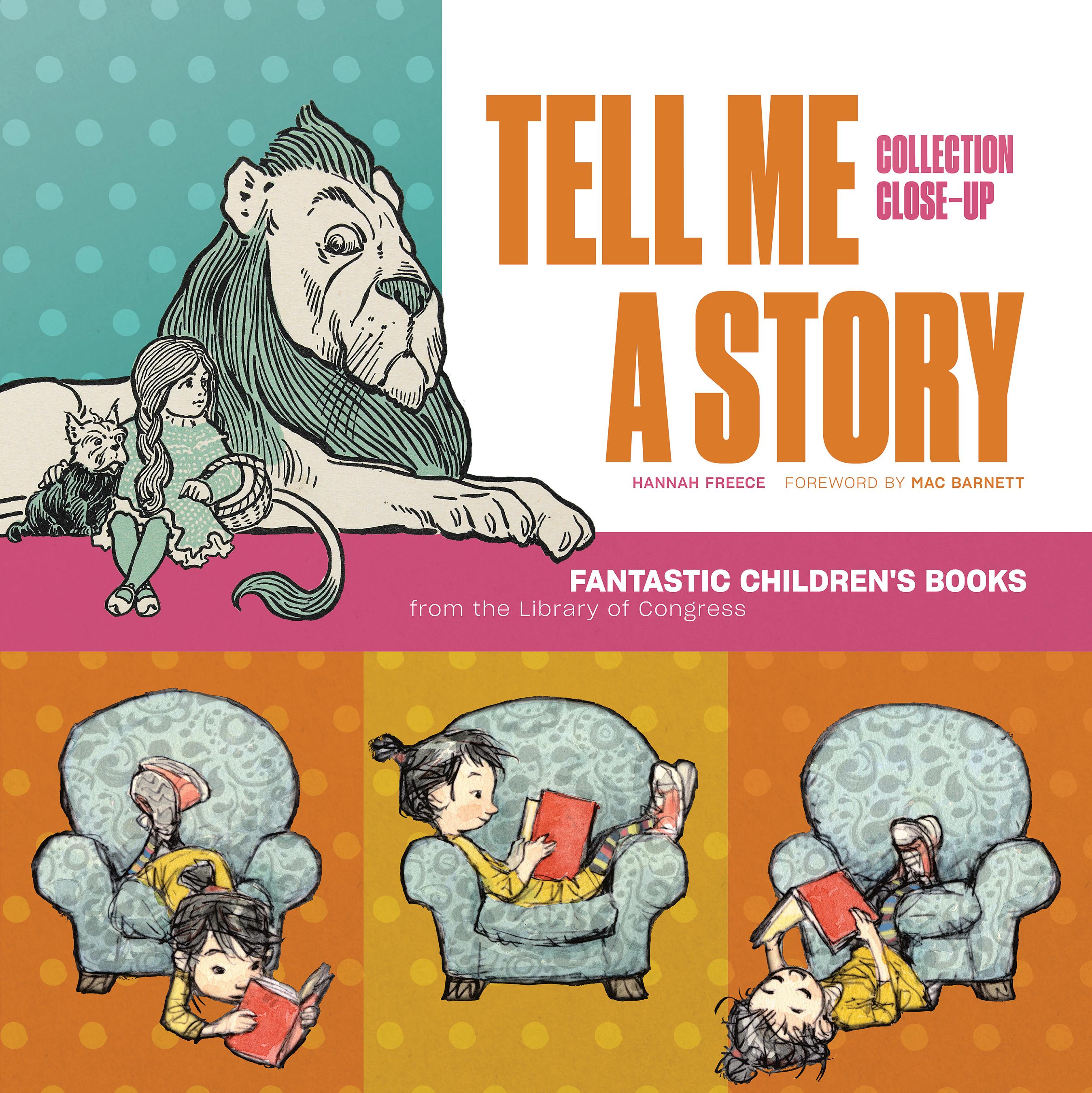

Book you've bought for the cover:

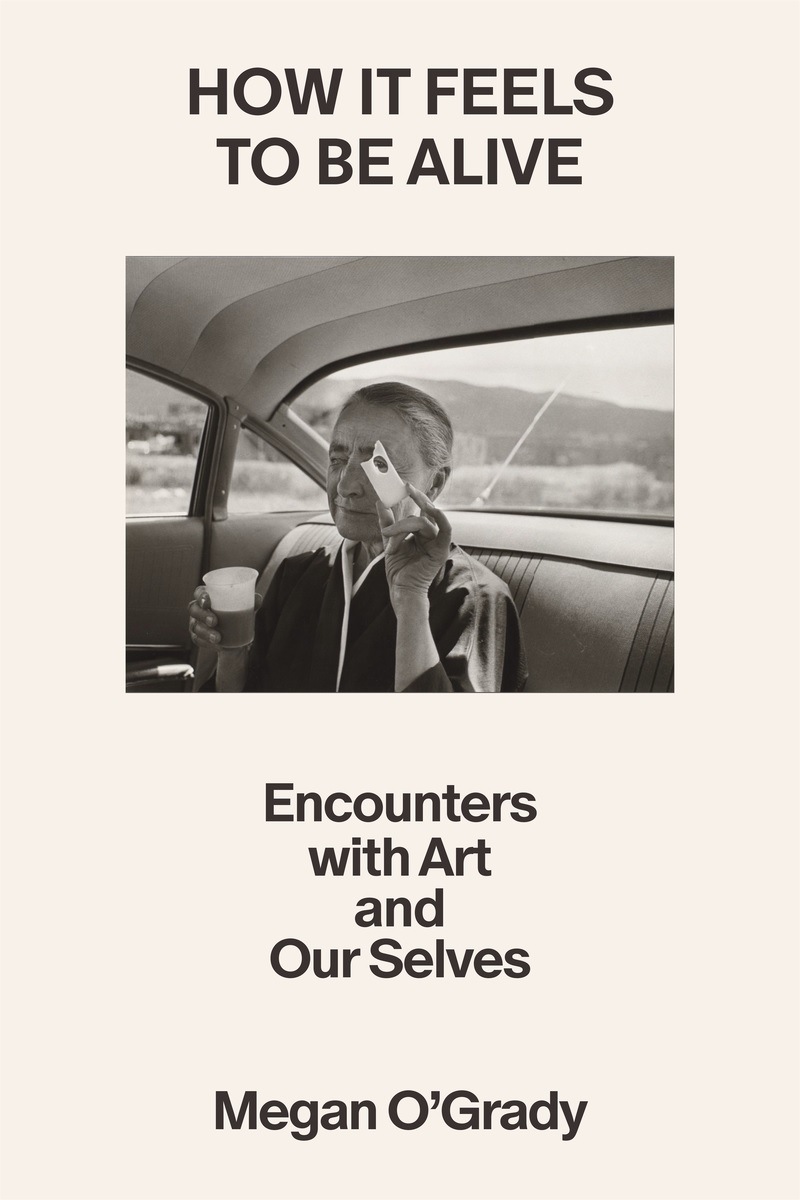

Book you've bought for the cover: Congratulations to art lovers who have never had someone say to them, "What purpose does art serve?" For aesthetes, the answer is obvious. At its most profound, art provides new perspectives, confronts injustice, assures those who feel like perpetual outsiders that they're not alone. Critic Megan O'Grady has always embraced conceptual artist Barbara Kruger's observation that art teaches a person, "through a kind of eloquent shorthand, how it feels to be alive." Knowing a good title when she hears one, O'Grady borrows those words for How It Feels to Be Alive, a collection of five essays in which she investigates the way art "provokes unanswerable questions about how to live in a fragmenting society." She has chosen works that raised "questions that still feel urgent to me" and "offered me an eloquent shorthand in an often-incoherent world."

Congratulations to art lovers who have never had someone say to them, "What purpose does art serve?" For aesthetes, the answer is obvious. At its most profound, art provides new perspectives, confronts injustice, assures those who feel like perpetual outsiders that they're not alone. Critic Megan O'Grady has always embraced conceptual artist Barbara Kruger's observation that art teaches a person, "through a kind of eloquent shorthand, how it feels to be alive." Knowing a good title when she hears one, O'Grady borrows those words for How It Feels to Be Alive, a collection of five essays in which she investigates the way art "provokes unanswerable questions about how to live in a fragmenting society." She has chosen works that raised "questions that still feel urgent to me" and "offered me an eloquent shorthand in an often-incoherent world."