|

| Photo: Sally Gall |

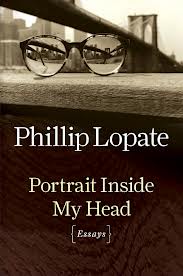

Phillip Lopate is the author of more than a dozen books, including the personal essay collections Bachelorhood, Against Joie de Vivre, Portrait of My Body and Waterfront. He directs the graduate nonfiction program at Columbia University and lives in Brooklyn with his wife and daughter. This week, Free Press simultaneously releases his two new works: Portrait Inside My Head: Essays and To Show and To Tell: The Craft of Literary Nonfiction.

On your nightstand now:

I've got a few collections by Max Beerbohm on my nightstand: And Even Now and Around Theatres. Beerbohm was a cheeky, hilarious personal essayist and a terrific drama critic, and I'm working on putting together a new collection of his pieces for New York Review Books. I've also been dipping into Louise Gluck's Poems 1962-2012, because I've long been a fan of hers (as well as a casual friend--I'm usually reading at least one book by someone I know). She is spare and powerful and the genuine article. I want to trace her progression from the early, well-mannered poems to the searingly personal ones, to the later ones speaking through various personae. And finally, I've been reading David Thomson's The Big Screen and finding it very satisfying, because he's so quirky and independent in his judgments, and the book itself is fearlessly outspoken, the way film criticism should be. Of course, I disagree with him at least 30% of the time, but I cherish his no-holds-barred approach.

Favorite book when you were a child:

I'd have to say Robert Louis Stevenson's Kidnapped. There was something about that adventure story of a boy on his own in a scary world, cut off from family and falling in with a swashbuckling man whom he idolizes, and who becomes a surrogate father/older brother to him, that spoke directly to my own hunger for a more engaging, capable, confident father than the one I had. Ever since, I've been intrigued with Stevenson, not only the boy's adventure storyteller, but the essayist, the travel writer, the invalid who married an older woman with children and ended up in the South Seas.

Your top five authors:

Your top five authors:

These are the top writers who shaped me when I was an adolescent: Fyodor Dostoevsky, Friedrich Nietzsche, Henry Fielding, Denis Diderot, Italo Svevo and Machado de Assis. They were all ironists, and I fell under the spell of Notes from Underground, Rameau's Nephew, Confessions of Zeno, Epitaph for a Small Winner, all that sort of mischievous, prickly, curmudgeonly, antisocial discourse, as well as Nietzsche's impish paradoxes and provocations. Some decades later, when I switched from fiction to essay-writing, Montaigne became my idol, and not far behind him, William Hazlitt, Charles Lamb, Walter Benjamin.... Gee, have I already exceeded five? Impossible to keep to that low number, I have so many favorite authors.

Book you've faked reading:

Midnight's Children by Salman Rushdie. I've always heard it's his best book, a masterpiece, but I started off by reading Rushide's Shame, which I found blustery, overwritten and too pleased with its vulgarities, and couldn't bring myself to tackle his earlier, most likely better novel.

Book you've been an evangelist for:

I always try to get my students to read Sei Shonagan's The Pillow Book. This irresistible grab-bag of poetic nature descriptions, likes, pet peeves, gossipy vignettes and portraits of court life by the 10th-century Japanese noblewoman has an air of total freedom about it, and as such is or should be an inspiration to all aspiring writers. She claims she wrote it just for her own pleasure, as a private diary, and she certainly couldn't care less whether she was offending the conventional sensibilities of her time. A tough-minded lady and a great free-wheeling character to meet on the page. I often find myself thinking, Why don't I just follow her lead, abandon all plot or subject matter and write my own Pillow Book? But I don't have the nerve.

Book you've bought for the cover:

I, Etcetera by Susan Sontag. That's the one with Sontag lounging on a couch, her legs going on forever, while she stares coolly and defiantly at the camera. To return to the above refrain, I knew Sontag off and on for years, and never found her to be quite as glamorous as she came across in photographs. Though I was immensely influenced by her evocative, heady essay-writing style, I also had mixed feelings about some of her work, which ambivalence I later explored in my Notes on Sontag. In any case, I just had to buy that book.

Book that changed your life:

Book that changed your life:

One book that changed my life was Jane Jacobs's The Death and Life of Great American Cities. I had been a more or less unconscious lover of urban experience, and suddenly this book gave me the key, the code to understand what it was I valued so in the daily, rough-and-tumble encounters of street life. Later on I came to question some of her anti-planning biases, but on the whole I have remained a staunch Jacobite in my approach to cities.

Favorite line from a book:

"Never, never, never, never, never," which King Lear pronounces while holding the body of his dead daughter, Cordelia. The finality of it, the austere rigor, raised a shiver up my back. For all of Shakespeare's magnificent language, when push came to shove, all he had to say to explain sudden grief was never, never, never, never, never.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Flaubert's Sentimental Education made a great impression on me when I read it the first time in college at 19 years old. I think I was particularly taken with the tense dynamics of friendship between the protagonist, Frederic, and his envious pal, Deslauriers (with whom I identified). Friendship has been a lifetime preoccupation of mine, and I would give a lot to know if the novel would affect me now as deeply. On the other hand, I've found it is sometimes a mistake to go back to those books that shattered you when you were younger. You may be in for a real disillusionment.

"This is my second year as National Ambassador for Young People's Literature, and I plan to spend the year writing for young people and also educating parents, guardians and teenagers about how America’s literacy gap can be solved.... I'll be writing about how teenagers, especially boys, can overcome their feelings of being defeated and how they can get back into the game. Working with the Library of Congress, and the Every Child a Reader Foundation, I hope to make a small difference and look forward to the year doing what I love."

"This is my second year as National Ambassador for Young People's Literature, and I plan to spend the year writing for young people and also educating parents, guardians and teenagers about how America’s literacy gap can be solved.... I'll be writing about how teenagers, especially boys, can overcome their feelings of being defeated and how they can get back into the game. Working with the Library of Congress, and the Every Child a Reader Foundation, I hope to make a small difference and look forward to the year doing what I love."

Rowman & Littlefield is consolidating its imprints and is focusing Rowman & Littlefield as "the primary vehicle for its academic, reference, trade, and textbooks." As a result, Scarecrow Press, Altamira Press and Jason Aronson will be folded into Rowman & Littlefield. Among imprints that are remaining separate: Lexington Books, which will continue to focus on academic monographs; Sundance-Newbridge, which will continue to publish educational materials for grades K-8; and Bernan, which will publish and distribute government and intergovernmental publications such as The Statistical Abstract of the United States, which it co-published in December with Pro-Quest.

Rowman & Littlefield is consolidating its imprints and is focusing Rowman & Littlefield as "the primary vehicle for its academic, reference, trade, and textbooks." As a result, Scarecrow Press, Altamira Press and Jason Aronson will be folded into Rowman & Littlefield. Among imprints that are remaining separate: Lexington Books, which will continue to focus on academic monographs; Sundance-Newbridge, which will continue to publish educational materials for grades K-8; and Bernan, which will publish and distribute government and intergovernmental publications such as The Statistical Abstract of the United States, which it co-published in December with Pro-Quest.

Michael Tamblyn has been promoted to the position of chief content officer at Kobo, where he will be responsible for the company's content acquisition and sales, publisher and industry relations, and localized merchandising experiences across all of Kobo's online and mobile services. In a statement, the company described Tamblyn as "a driving force in bolstering Kobo's content offering since the company was founded" and noted that he also spearheaded the launch of Kobo's self-publishing service, Kobo Writing Life.

Michael Tamblyn has been promoted to the position of chief content officer at Kobo, where he will be responsible for the company's content acquisition and sales, publisher and industry relations, and localized merchandising experiences across all of Kobo's online and mobile services. In a statement, the company described Tamblyn as "a driving force in bolstering Kobo's content offering since the company was founded" and noted that he also spearheaded the launch of Kobo's self-publishing service, Kobo Writing Life. After eight years in business, the

After eight years in business, the  While Queen Elizabeth still tops the list of the "

While Queen Elizabeth still tops the list of the " Last Saturday, in Berkeley, Calif., Annie Barrows attended the world premiere of Ivy + Bean: The Musical, an original production of the Bay Area Children's Theatre based on her Ivy + Bean series. Chronicle Books partnered with the Theatre to invite booksellers and librarians to watch, and afterward, Barrows and the cast mingled with young fans. From l.: Annie Barrows; Megan Putman, who plays Ivy; Anne Whaling of Mrs. Dalloway's Bookstore in Berkeley; and Chronicle Books editorial assistant Taylor Norman.

Last Saturday, in Berkeley, Calif., Annie Barrows attended the world premiere of Ivy + Bean: The Musical, an original production of the Bay Area Children's Theatre based on her Ivy + Bean series. Chronicle Books partnered with the Theatre to invite booksellers and librarians to watch, and afterward, Barrows and the cast mingled with young fans. From l.: Annie Barrows; Megan Putman, who plays Ivy; Anne Whaling of Mrs. Dalloway's Bookstore in Berkeley; and Chronicle Books editorial assistant Taylor Norman. "We've all seen signs banning cell phones, food, and drinks. But these rules cover issues that might not be common to all libraries," Mental Floss observed in highlighting "

"We've all seen signs banning cell phones, food, and drinks. But these rules cover issues that might not be common to all libraries," Mental Floss observed in highlighting " Jacket Copy offered a "quick tour through

Jacket Copy offered a "quick tour through  Man in the Empty Suit

Man in the Empty Suit

Your top five authors:

Your top five authors: Book that changed your life:

Book that changed your life: Using Emily Dickinson's poetry and the facts known about her life, Michaela MacColl (Prisoners in the Palace) fashions a suspenseful, often humorous historical novel in which a 15-year-old Emily plays detective when a stranger to town winds up facedown in her family's pond.

Using Emily Dickinson's poetry and the facts known about her life, Michaela MacColl (Prisoners in the Palace) fashions a suspenseful, often humorous historical novel in which a 15-year-old Emily plays detective when a stranger to town winds up facedown in her family's pond.