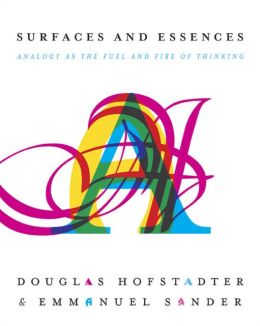

Douglas Hofstadter was just 34 years old when he published the 1979 Pulitzer Prize‑winning Gödel, Escher, Bach, a profoundly original and bravura achievement that vaulted across disciplines to explore how consciousness and a sense of "self" might arise from inanimate matter. It became a cult classic, a shared "nerd bible" (as Time called it) for a generation of educated readers. Nearly 30 years later, I Am a Strange Loop (2007) offered a more contained and personal explanation of consciousness and the physical nature of thought.

Douglas Hofstadter was just 34 years old when he published the 1979 Pulitzer Prize‑winning Gödel, Escher, Bach, a profoundly original and bravura achievement that vaulted across disciplines to explore how consciousness and a sense of "self" might arise from inanimate matter. It became a cult classic, a shared "nerd bible" (as Time called it) for a generation of educated readers. Nearly 30 years later, I Am a Strange Loop (2007) offered a more contained and personal explanation of consciousness and the physical nature of thought.

In Surfaces and Essences, Hofstadter and French cognitive psychologist Emmanuel Sander address the central role of analogy in thought, an important research focus in cognitive science. The result is a definitive and emphatic affirmation of the argument that analogies are essential for concepts and thinking, permeating every moment and every aspect of thought. We understand the new and unfamiliar because we associate it with something familiar. Analogy is thus the core of thinking.

Hofstadter and Sander spin out this idea on multiple levels, from the personal to the cultural, from specific words, phrases and situations to abstract ideas and ultimately, to creativity. They explain that the mechanism that allows us to use the simplest words is the same mechanism that has enabled humanity's most groundbreaking discoveries and its greatest accomplishments.

They also take unbridled and often infectious pleasure in backing up each key step in their argument with a dizzying array of examples, often laced with playful humor. Surfaces and Essences shares with Hofstadter's earlier books his joy in exploration and ideas. Its frequent examples from children to show the preconscious nature and development of analogies are effective and warm.

Surfaces and Essences is not a review of the research leading to its conclusions. Its purpose is to show how analogy works at successive levels. It relies on examples that illustrate rather than prove, but which often lack inherent interest beyond the point they support and, in their sheer number, can seem excessive, distracting from the main argument. The result is unnecessarily difficult reading, especially in the earlier chapters. Later chapters on creativity and scientific achievement are more persuasive, full of insights and ideas. The extended focus on Einstein's dependence on snowballing analogies for his "grand train" of discoveries provides the strongest narrative thread, making this section the most engaging--a compelling capstone to this deep dive into human thought. --Jeanette Zwart, freelance writer and reviewer

Shelf Talker: Like the iconic Gödel, Escher, Bach, Hofstadter's latest is serious idea-driven nonfiction for general readers--especially fans of Stephen Pinker, George Lakoff and Daniel Dennett.

"Every thought and every prayer goes out to the victims and their families and loved ones. What a senseless act of waste and violence.... It's hard to imagine any people more inspiring than all those people who dashed across Boylston Street within seconds of the first explosion, and rushed to the aid of the injured. Didn't give their own safety a thought. Made me proud to be a member of the human race, which I think was the exact opposite of the effect the bomber was hoping for....

"Every thought and every prayer goes out to the victims and their families and loved ones. What a senseless act of waste and violence.... It's hard to imagine any people more inspiring than all those people who dashed across Boylston Street within seconds of the first explosion, and rushed to the aid of the injured. Didn't give their own safety a thought. Made me proud to be a member of the human race, which I think was the exact opposite of the effect the bomber was hoping for....

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.S1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

Kobo has introduced the limited-edition

Kobo has introduced the limited-edition SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

Simon & Schuster will launch a one-year pilot program through which its catalogue of e-books will be made available to the New York Public Library and Brooklyn Public April 30, and the Queens Library by mid-May. S&S becomes the last of the Big Six publishers to sell its e-books to libraries for lending. The library can offer an unlimited number of checkouts during the one-year term for which it has purchased a copy. Each title is usable for a year from the date of purchase and may be checked out by one user at a time.

Simon & Schuster will launch a one-year pilot program through which its catalogue of e-books will be made available to the New York Public Library and Brooklyn Public April 30, and the Queens Library by mid-May. S&S becomes the last of the Big Six publishers to sell its e-books to libraries for lending. The library can offer an unlimited number of checkouts during the one-year term for which it has purchased a copy. Each title is usable for a year from the date of purchase and may be checked out by one user at a time.  This September, the U.K.'s Booksellers Association and Publishers Association will launch a trade-wide

This September, the U.K.'s Booksellers Association and Publishers Association will launch a trade-wide

Ira Sandperl

Ira Sandperl The Last Bookshop

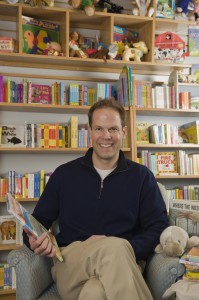

The Last Bookshop Dr. John Hutton "wanted kids to read books and play outside. He wanted their parents to unplug the kids' televisions and computers.... So he focused on more books and less screen time. That would be his issue," the Cincinnati Enquirer reported in its profile of

Dr. John Hutton "wanted kids to read books and play outside. He wanted their parents to unplug the kids' televisions and computers.... So he focused on more books and less screen time. That would be his issue," the Cincinnati Enquirer reported in its profile of  DIESEL, a Bookstore

DIESEL, a Bookstore The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen

The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England's Most Notorious Queen

Winners of this year's

Winners of this year's

Douglas Hofstadter was just 34 years old when he published the 1979 Pulitzer Prize‑winning Gödel, Escher, Bach, a profoundly original and bravura achievement that vaulted across disciplines to explore how consciousness and a sense of "self" might arise from inanimate matter. It became a cult classic, a shared "nerd bible" (as Time called it) for a generation of educated readers. Nearly 30 years later, I Am a Strange Loop (2007) offered a more contained and personal explanation of consciousness and the physical nature of thought.

Douglas Hofstadter was just 34 years old when he published the 1979 Pulitzer Prize‑winning Gödel, Escher, Bach, a profoundly original and bravura achievement that vaulted across disciplines to explore how consciousness and a sense of "self" might arise from inanimate matter. It became a cult classic, a shared "nerd bible" (as Time called it) for a generation of educated readers. Nearly 30 years later, I Am a Strange Loop (2007) offered a more contained and personal explanation of consciousness and the physical nature of thought.