_with_Laura_Ingalls_Wilder_Award_winner_Tomie_dePaola_and_Caroline_Ward.jpg) |

| Stoddard (l.) with Tomie dePaola and Caroline Ward. |

Jewell Stoddard co-founded the Cheshire Cat children's bookstore in Washington, D.C., in 1977; the store closed and Stoddard joined Politics & Prose as children's buyer in 1999. Stoddard co-founded and has served on the Capitol Choices committee since 1995, and also served on the 1994 Caldecott Committee and on the first committee to nominate the Inaugural National Children's Literature Ambassador (the committee chose Jon Scieszka). She retired in 2013.

What inspired you to start the Cheshire Cat?

I partnered with three others women: Charlotte Berman, Pam Sacks and Helen "Greenie" Neuberg. Greenie and I had toyed with starting a school--we were both teachers before. But then Pam mentioned a friend who had a wonderful children's bookstore in South Africa. We'd had a terrible time finding children's books for our classrooms. We were book buyers, book readers and book lovers, and we decided to go for it.

|

| Opening day at the Cheshire Cat |

Where did people buy children's books?

There were some book fair companies like Scholastic that worked with schools; and there were some children's toy stores that had a few books. There was one on Connecticut Avenue that had three bookcases of Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys. The Cheshire Cat was down the block from that.

Tell us about your early days.

Well, we got into the space on July 15, opened the door and the burglar alarm went off. Five minutes later, three policemen came with drawn pistols. That was our introduction to bookselling.

The day we opened, we had four copies of Pat the Bunny and five Goodnight Moons, and they didn't last the day. That was partly because Amy Carter [daughter of President Jimmy Carter] came. She'd read an article about our opening in the Evening Star. So her limousine and the Secret Service pulled up right outside, which almost stopped traffic. That started us off with a bang. We were out of half the store by the end of the weekend. Greenie and I were in the cellar ordering books as fast as we could, and that went on all fall. It was great fun.

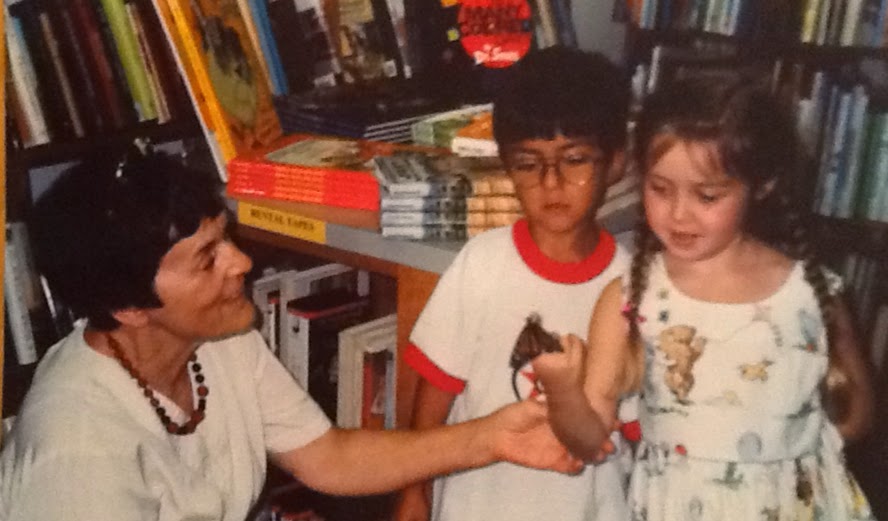

|

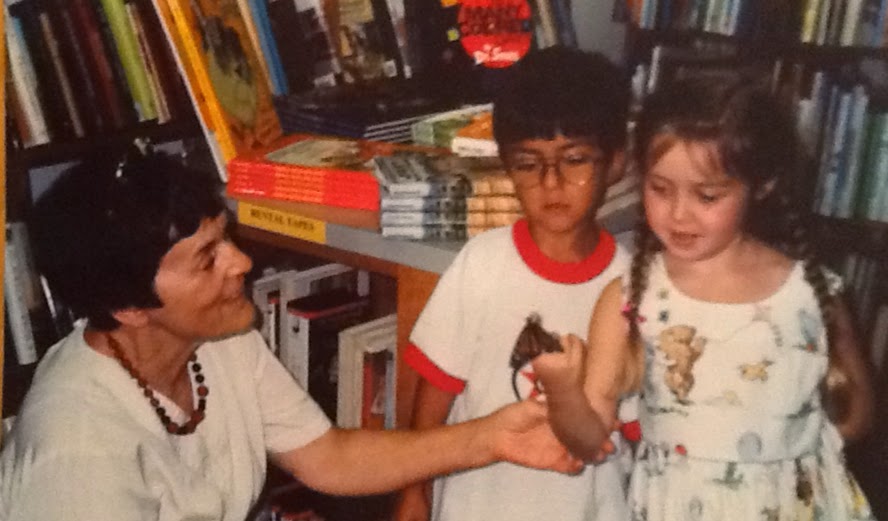

| Stoddard helping young customers, 1997 |

Did you get to be friends with publishers?

Yes, some reached out to us right away. At that point, Ursula Nordstrom was still in charge of Harper, and she sent someone to meet with us. I did get to meet the lady herself, too--a great lady. Later, Charlotte Zolotow was in charge, and she was also wonderful. I always felt Ursula Nordstrom's spirit was still there.

Also at Harper, Bill Morris was incredibly kind to us. He once called me out of the blue and said, in his thick Southern accent, "Jewell, it seems to me that we should be supporting you, because you do so much for Harper books. Why don't I put you down for a thousand dollars [for co-op]?" Well, as you can imagine, I said, "Bill--be my guest!" And that's how it worked from then on. I never remembered to send in the paperwork, so Bill would call and say, "Jewell, I don't see that you've made a claim for co-op advertising. Let's see, how much did you spend?" And then he'd just give me 10% of whatever I told him.

So many publishers were wonderful to us. Margaret McElderry--I think at that point she was with Simon & Schuster--we loved her. Phyllis Fogelman at Dial and George Nicholson at Doubleday. And one other editor who I adored was Susan Hirschman of Greenwillow. She brought Kevin [Henkes] and Ann Jonas (who was trembling!) and Donald Crews to the Cheshire Cat.

Of course, there were some publishers who were not used to dealing with anyone but schools, and they knew that they had to get the books there by September and January. So we'd order books, and then six weeks later they'd arrive. So we had to try to plan ahead with them.

|

| Peggy Parish at Cheshire Cat |

Do you have some favorite anecdotes?

When Peggy Parish came it got so crowded that we kicked all the grownups out of the store and made them wait outside. And there was a moment, when I looked at Peggy--and Peggy looked at me--and she said, "How on earth are we going to get them all back together?" So eventually, what we did was, Greenie and Pam would take a child out to the sidewalk and say, "What am I bid for this kid?" There were hundreds of parents out there on Connecticut Avenue.

The other one--you know this story well, Allie!--is when Eric Carle came. I used to hatch butterflies in the store, and we would always put any books about butterflies next to them. And one time, a caterpillar formed its chrysalis on a copy of The Very Hungry Caterpillar. And I got to show Eric that when he came to the store--the chrysalis was there, dangling from the cover.

If I could go back in time to any moment, it might be that, just to see the look on his face.

It was magical.

What was the guiding vision for the Cheshire Cat?

We wanted to be sure that we served the whole community. The first author we had was Eloise Greenfield, for Honey, I Love. The second was Katherine Paterson, who won the Newbery that year for Bridge to Terabithia. And then we had David Macaulay. So we had poetry, fiction and nonfiction. And it was really important to us to feature black authors and illustrators. Eloise Greenfield came many times, and so did her mother, after they wrote Childtimes together. There were the Dillons [Leo and Diane] and Jerry Pinkney, Lucille Clifton and her wonderful Everett Anderson books, which I still think are marvelous. We had all of John Steptoe's, and of course Virginia Hamilton's, so there were some tremendous people at this time.

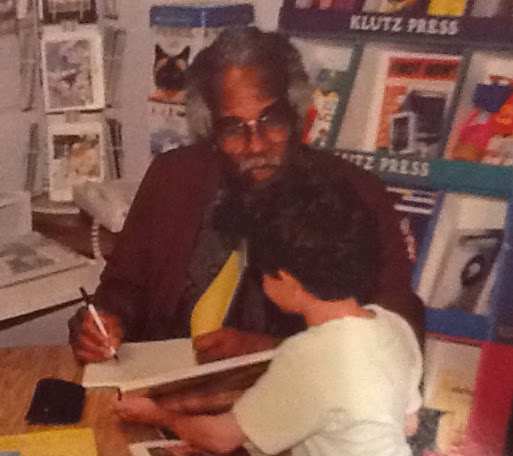

|

| Ashley Bryan |

Mildred Taylor?

God, yes. I got to see her a few times, which was really lucky, because she didn't do bookstores. It was painful for her to even come to the awards. Ashley [Bryan] also became a good friend, as did James Ransome.

Where did your passion for promoting diversity come from?

One of the seminal things in my life, as an ex-Southerner, was Nancy Larrick's piece ["The All-White World of Children's Books," the Saturday Review, September 1965]. That just blew me away. I knew Nancy, and became good friends with her. Here was a Southern lady, her family owned grand property in Virginia, but she was just rabid on the subject, and shocked and horrified that when she looked for books for black children, there weren't any. I think Christopher [Myers] and Walter [Dean Myers]'s New York Times pieces ["The Apartheid of Children’s Literature"; "Where Are the People of Color in Children's Books?"] are the modern equivalent. Three days later, the country was talking about it in a way they hadn't before, even though lots of people had pushed it, lots of people had talked about it, but somehow, it was really ripe for a national story. And I think it will snowball. It is snowballing. And I'm just thrilled.

In book displays at Politics & Prose, you always pushed for as much diversity as possible.

Oh, absolutely. For the first few months after we opened the Cheshire Cat, new people would come in and say, "Where are your black books?" or "Where are your Christian books?" And we would say, "Well, there are some here, and some here, and some here...." "Why don't you put them all together?" they'd ask. And we would say, "That's just not how we want to display books. We want white people to see African-American books, and we want them to buy them, and they're not going to buy them if they're off in a ghetto by themselves."

People felt that way about a lot of categories. "Where are your classics? Where are your Newberys?" They wanted us to isolate all these different categories, and we just weren't willing to do that. The only thing we did isolate were picture book paperbacks from hardbacks, because they're too thin to be seen. So we developed special bookshelves to display them all face-out.

Did you find that integrating the books made life harder?

Oh, no. It meant that we had to be more involved with customers, but that was what we wanted.

So you did a lot of handselling.

Yes. And that's the name of the game in independent bookstores!

Did white people buy books by black authors, about black people, because of that?

Yes, absolutely. And our author events with black authors were crowded with white people, all buying books.

When you first started, "diversity" meant black as well as white, right?

Yes.

When did it start to expand beyond that?

Hmmm. You know, there were some Hispanic authors early on. And then Children's Book Press started in California, specifically for Latin American writers and illustrators. So of course, people were trying. I was on the Caldecott committee the year Allen Say won for Grandfather's Journey (1994). Lee and Low has been around 25 years now, and I think they've just done a wonderful job. Jason [Low] has really pushed the diversity issue out into the public, and he's like a dog with a bone--he's not going to let it go. It thrills me. And it's growing now--slowly, but growing.

As someone who was there when this was all starting, what's your take on the way things are now?

Things are definitely better now, but they're not nearly good enough. I don't think there's any aspect of our culture that's good enough when it comes to race relations.

What's your advice to booksellers who want to push diversity?

Carry a lot of titles, and put as many of them face out as you can. And have your staff read them and see that they're for everybody. We advertised in a lot of local newspapers that were in black communities. And we were immediately adopted by D.C. librarians and by the Library of Congress.

If you were going to start up a new children's bookstore now, what would your vision be?

I would want it to be in as mixed a community as I could find. If I couldn't find one, I'd try to build one.

If you could change one thing about the industry, what would it be?

I would have publishers stop trying to publish for the bottom line on every single book they do. In the old days, for example--well, take Susan Hirschman. She didn't make money on Kevin [Henkes]'s first book. Or even his second book. But she nurtured him. Phyllis [Fogelman] did the same with Tom Feelings. All those years, they believed in them, they nurtured them, they pushed, prodded and scolded them.

You weren't expected to make a big profit off your first books.

Right. Take Jambo Means Hello by Muriel and Tom Feelings, and their other early books. They stayed in print for a long time because they didn't initially print huge numbers. You didn't have to have 10,000 in sales every quarter, or whatever they want now.

The emphasis on bestsellers changed things a lot. In adult publishing, too. The world is different now. The message is "You've gotta make a blast with your first book." And not everyone can be Mo Willems. But I love Mo Willems! Make sure you get that. There are some wonderful people who've made it big right off the bat, like Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith. And I love Harry Potter, too. But I liked the nurturing model better.

What do children stand to gain from having diverse books available to them? What do they stand to lose by not having them?

I don't think we can ever become an integrated society until we have diverse books. If children grow up not knowing how others live, not knowing how others are, what their joys are, how can they know what the world is really like? It's critical. --Allie Bruce

Bruce is a children's librarian at the Bank Street College of Education, and worked alongside Stoddard at Politics & Prose from 2007 to 2009. Bruce is also a member of the We Need Diverse Books team.

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

In the third quarter ended November 1, revenue at Books-A-Million rose 1.2%, to $101.2 million and the net loss was $6.9 million, identical with the same period last year. Sales at stores open at least a year rose 1.8%.

In the third quarter ended November 1, revenue at Books-A-Million rose 1.2%, to $101.2 million and the net loss was $6.9 million, identical with the same period last year. Sales at stores open at least a year rose 1.8%. The American Booksellers Association has named

The American Booksellers Association has named  When registration opens for

When registration opens for

Garbed as their characters, "penny-dreadful" authors/publishers Katherine L. Morris and David L. Drake (seated, center) celebrated the release of their novel, London: Where It All Began, the illustrated print edition of their steampunk web serial,

Garbed as their characters, "penny-dreadful" authors/publishers Katherine L. Morris and David L. Drake (seated, center) celebrated the release of their novel, London: Where It All Began, the illustrated print edition of their steampunk web serial,  Congratulations to

Congratulations to  A

A  In the spirit of the season, USA Today columnist and author Rhonda Abrams offered "

In the spirit of the season, USA Today columnist and author Rhonda Abrams offered " Yoga for Cancer: A Guide to Managing Side Effects, Boosting Immunity, and Improving Recovery for Cancer Survivors

Yoga for Cancer: A Guide to Managing Side Effects, Boosting Immunity, and Improving Recovery for Cancer Survivors Brian K. Vaughan is the writer and co-creator of the graphic novels Y: The Last Man, Ex Machina, Runaways, Pride of Baghdad, The Hood, The Escapists and The Private Eye (a digital comic with artist Marcos Martin at

Brian K. Vaughan is the writer and co-creator of the graphic novels Y: The Last Man, Ex Machina, Runaways, Pride of Baghdad, The Hood, The Escapists and The Private Eye (a digital comic with artist Marcos Martin at  Book you're an evangelist for:

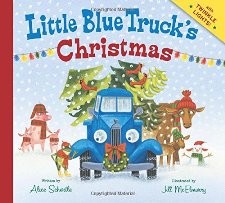

Book you're an evangelist for: Little Blue Truck's Christmas by Alice Schertle, illus. by Jill McElmurry (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $14.99, hardcover, 9780544320413, 24p., ages 1-3, September 23, 2014)

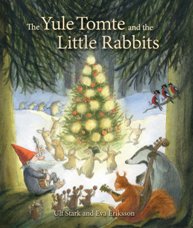

Little Blue Truck's Christmas by Alice Schertle, illus. by Jill McElmurry (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $14.99, hardcover, 9780544320413, 24p., ages 1-3, September 23, 2014)  The Yule Tomte and the Little Rabbits: A Christmas Story for Advent by Ulf Stark, illus. by Eva Eriksson (Floris, $24.95, hardcover, 9781782501367, 102p., ages 4-up, October 2014)

The Yule Tomte and the Little Rabbits: A Christmas Story for Advent by Ulf Stark, illus. by Eva Eriksson (Floris, $24.95, hardcover, 9781782501367, 102p., ages 4-up, October 2014)  Santa Clauses: Short Poems from the North Pole by Bob Raczka, illus. by Chuck Groenink (Carolrhoda/Lerner, $16.95, hardcover, 9781467718059, 32p., ages 5-9, September 30, 2014)

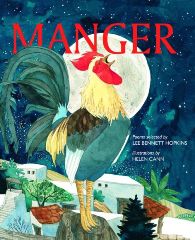

Santa Clauses: Short Poems from the North Pole by Bob Raczka, illus. by Chuck Groenink (Carolrhoda/Lerner, $16.95, hardcover, 9781467718059, 32p., ages 5-9, September 30, 2014)  Manger, edited by Lee Bennett Hopkins, illus. by Helen Cann (Eerdmans, $16, hardcover, 9780802854193, 34p., ages 4-8, September 1, 2014)

Manger, edited by Lee Bennett Hopkins, illus. by Helen Cann (Eerdmans, $16, hardcover, 9780802854193, 34p., ages 4-8, September 1, 2014)  Here Comes Santa Cat by Deborah Underwood, illus. by Claudia Rueda (Dial/Penguin, $16.99, hardcover, 9780803741003, 88p., ages 3-5, October 21, 2014)

Here Comes Santa Cat by Deborah Underwood, illus. by Claudia Rueda (Dial/Penguin, $16.99, hardcover, 9780803741003, 88p., ages 3-5, October 21, 2014)  'Twas Nochebuena: A Christmas Story in English and Spanish by Roseanne Greenfield Thong, illus. by Sara Palacios (Viking, $16.99, hardcover, 9780670016341, 32p., ages 3-5, October 16, 2014)

'Twas Nochebuena: A Christmas Story in English and Spanish by Roseanne Greenfield Thong, illus. by Sara Palacios (Viking, $16.99, hardcover, 9780670016341, 32p., ages 3-5, October 16, 2014)  I Know an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Dreidel by Caryn Yacowitz, illus. by David Slonim (Levine/Scholastic, $17.99, hardcover, 9780439915304, 32p., ages 6-9, September 30, 2014) This comical send-up of a standard rhyme stars a spunky grandmother and a host of visual puns. After a cat deposits a dreidel on the grandmother's bagel, she swallows it ("Perhaps it's fatal"). Slonim slips in nods to the Mona Lisa, American Gothic, Munch's The Scream and Hopper's Nighthawks among many others. Children will enjoy the slapstick humor, and grown-ups will appreciate the parody.

I Know an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Dreidel by Caryn Yacowitz, illus. by David Slonim (Levine/Scholastic, $17.99, hardcover, 9780439915304, 32p., ages 6-9, September 30, 2014) This comical send-up of a standard rhyme stars a spunky grandmother and a host of visual puns. After a cat deposits a dreidel on the grandmother's bagel, she swallows it ("Perhaps it's fatal"). Slonim slips in nods to the Mona Lisa, American Gothic, Munch's The Scream and Hopper's Nighthawks among many others. Children will enjoy the slapstick humor, and grown-ups will appreciate the parody. My True Love Gave to Me: Twelve Holiday Stories, edited by Stephanie Perkins (St. Martin's Griffin, $18.99, hardcover, 9781250059307, 320p., ages 12-up, October 14, 2014)

My True Love Gave to Me: Twelve Holiday Stories, edited by Stephanie Perkins (St. Martin's Griffin, $18.99, hardcover, 9781250059307, 320p., ages 12-up, October 14, 2014)  In the first (Knopf, $16.99, hardcover, 9780385754590, 40p., originally published in 1954), Roger Duvoisin's illustrations span chimney-height pages that emphasize the "jolly old elf" during his descent (his belly barely clearing the narrow passage to the fireplace), with a festive palette of red, yellow, blue and green.

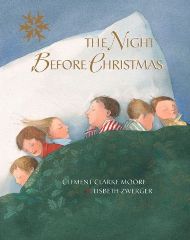

In the first (Knopf, $16.99, hardcover, 9780385754590, 40p., originally published in 1954), Roger Duvoisin's illustrations span chimney-height pages that emphasize the "jolly old elf" during his descent (his belly barely clearing the narrow passage to the fireplace), with a festive palette of red, yellow, blue and green. The other, illustrated by Lisbeth Zwerger (Minedition, $9.99, hardcover, 9789888240883, 32p., originally published in 2005), comes in a handsize volume that emphasizes the mystery of Santa's visit. St. Nick's European garb complements an urban setting, in which reindeer peek out from behind a tall chimney on a four-story Victorian building. --

The other, illustrated by Lisbeth Zwerger (Minedition, $9.99, hardcover, 9789888240883, 32p., originally published in 2005), comes in a handsize volume that emphasizes the mystery of Santa's visit. St. Nick's European garb complements an urban setting, in which reindeer peek out from behind a tall chimney on a four-story Victorian building. --_with_Laura_Ingalls_Wilder_Award_winner_Tomie_dePaola_and_Caroline_Ward.jpg)