In honor of St. Patrick's Day, we present an interview with Anne Enright, the inaugural Laureate for Irish Fiction and winner of the 2007 Man Booker Prize for The Gathering. Enright's next novel, The Green Road, is being published here by Norton on May 11.

In honor of St. Patrick's Day, we present an interview with Anne Enright, the inaugural Laureate for Irish Fiction and winner of the 2007 Man Booker Prize for The Gathering. Enright's next novel, The Green Road, is being published here by Norton on May 11.

You've spent time on the Green Road. What is it like?

In the spring of 2012, we took a long rent on a little house on the west coast of Ireland, with a view down to the limestone flats of the Flaggy Shore and across to the Aran Islands. Yeats, Synge and Lady Gregory all wrote about this place, as, more lately, did Heaney and Michael Longley. It is the iconic landscape of the Irish national revival and very beautiful.

Perhaps it was the change of location, but it was one of those times in my life when I wasn't entirely sure who I was anymore. Every day I would walk out and let the wind blow these questions out of my mind and also take in the wildness of the place. The green road is just that, an unpaved road that crosses the uplands of the Burren from Ballynahown to the Caher Valley, with a changing view from the Cliffs of Moher in the south to the Twelve Bens and Maumturk mountains in the far north, across Galway Bay.

Over the years, I had avoided what I call "the landscape solution" in Irish prose, where the writer puts the word "Atlantic" or "bog" in the story and some essential yearning in his character is fixed. But there I was myself, getting fixed on the green road, and it seemed to me that this was something I should allow myself to write about, now.

My father grew up on a small farm 30 miles down the coast from the green road, and I spent a lot of time there as a child. I have always written "out," always worked against the Irish tradition, and this book, which is about exile and return, also marks, for me, a kind of return. And what better place to come back to? There is nowhere that does leaving home and coming home better than the west coast of Ireland.

Many of the names in the book are references to Irish patriots. Why?

That may just be my little joke--although it was not a joke to the parents who named them. Both Dan Madigan and Rosaleen Considine come from strong, slightly different Irish patriotic traditions. I could untangle their deep history--which side each family took during the Civil War that followed the Irish War of Independence in 1922--but that deep history is often hidden in the west of Ireland; indeed, it is slightly taboo. This sense of taboo lingers in the first chapter of the book, but I was moving forward not back, so all that remains of that are the patriotic names of the children. It goes without saying that both sides in the Civil War were patriots, that was why it was such a painful time in Irish history. But yes, call them out! The honor roll! Daniel O'Connell, Constance Markewizc, Robert Emmet, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington--heroes all.

The gay marriage referendum is coming up in Ireland later this year. How do you feel your book speaks to this ongoing issue?

I have a character in the book who is gay, and I tried to stay true to the path he would take through life: it wasn't something I had complete control over, to be honest. Dan decides to get married--despite his difficulties loving his partner (or loving anyone, indeed)--and his sister is almost disappointed. "I thought you got away from all that," she says, meaning the great heterosexual institution of marriage. "I did get away from it," he says. "And now, I can do what I like."

Perhaps this reflects my own view as much as it does Dan's. People have great difficulties, they come through huge and wonderful personal battles, in order to become proper human beings who can love other human beings. I think that's all there is, really. In my own (heterosexual) case, marriage was not about giving in to conservative values but about radicalizing them and making them new.

Your book deals very delicately, and honestly, with the AIDS epidemic. Was this section particularly challenging to write?

Like many people in the arts, I knew people who were HIV positive and I lost people--or we lost people--to the disease. There was a feeling, in the early 1990s, that we were living through astonishing times, but this great sadness, which was both historical and deeply personal, has not made it into many novels. I wanted this chapter to be about love, because I remember a time of great love and of great courage. I did not want all that to be forgotten. I don't know if it was challenging to write; it was certainly deeply felt.

Can you describe your novel The Green Road?

Can you describe your novel The Green Road?

Four children grow up and move away from their childhood home in the west of Ireland. They go everywhere, have full, interesting and complex lives, and then, in 2005, their elderly mother declares she is going to sell the house. So they all troop back for their Irish family Christmas and try to sleep one last time in their old beds. They bring their inner child home with them, only to meet their outer mother, Rosaleen: a woman who is sometimes wonderful and always difficult. The book is about compassion, how the heart gets smaller as we age, and how we try to fix that, if we can.

Your books often revolve around family. Why?

Actually, The Gathering was, for me, about memory and history. The large family in that book also begged large questions: If your birth was an accident, then what did your death matter? For me, the family is just a natural space in which to think about the big issues.

I suppose The Green Road is more "about" family than my other books, though I thought I was just using the family space to think about compassion and selfishness, about feelings of abandonment and of connection, exile and return. One of the things I like to do is to take that very male tradition of "lonely," dissociated or bleak writing and I add in a mother. I do this because mothers are so absent in heterosexual male fiction--so impossible, somehow--and I am interested in working with this sense of "impossibility." Psychology talks about nothing but the mother, the novel talks of everything but her. It is not just that I myself have a mother (funny, that), but that I am a mother. I am an Irish Mammy. Hurrah!

At the center of your novel is the fascinating character of Rosaleen. Where did she come from?

Well, you know, I made her up. I took a selection of tiny vanities and seeded them in this character, to see how they would grow old. The Internet is full of people giving out about their selfish, appalling mothers--many of them sound a bit appalling themselves--so I took a few cues from there. But Rosaleen is very much herself. She is someone I can see very clearly, in my mind's eye, and she is not appalling in any real sense. She is hard to please, prone to disappointment, she drives her children mad, but I think, if you met her at, say, a wedding, you would find her very good company, completely charming, the kind of woman who makes everything about her glow.

Rosaleen's restless children live all over the globe but return to Ireland when their family home is about to be sold. How important is home and can you ever escape it?

You can free yourself of many kinds of difficulty, over time, but home is where those difficulties began and where we think they can be solved, so the pull toward it is very strong. It is, besides, nice. It is good to feel "at home."

You once said "the periphery has always been a more interesting place for me." Can you explain?

When I started out at the age of 20 or so, I thought that female fiction was going to be the most exciting thing ever. Things were opening up; there was so much to say that had not been said before. In fact, there was no huge welcome for the female voice in Ireland; the male tradition continued to dominate for the next 30 years of my writing life--and 30 years is a long time. I came to revel in my role as an outsider and also to dislike it. These are the tensions that, if they don't kill your work, make it more interesting. I decided it was more interesting to be on the edge of things. And it is. But this was a decision I was obliged, somehow, to make.

Things have shifted with the generation of Irish writers that has emerged since the economic crash, in the last five years or so. I think there is real change in the air now. And I was recently made the first Laureate for Irish Fiction, so I can hardly claim to be excluded--outside, with my nose pressed up against the glass. The Green Road is less "edgy" in some ways than my other work: there is more of a sense of scope, of shifting from one to another character's point of view. Perhaps it was time to move in from the periphery and pitch my tent on the middle ground for once. Just for a while.

The Barnes & Noble in the Crossroads Towne Center in Gilbert, Ariz., is

The Barnes & Noble in the Crossroads Towne Center in Gilbert, Ariz., is

Keep the Change: A Collector's Tales of Lucky Pennies, Counterfeit C-Notes, and Other Curious Currency

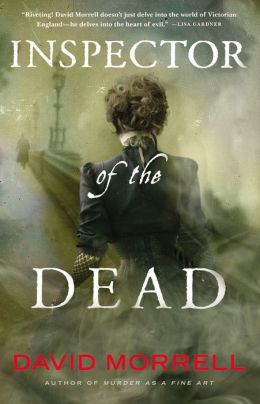

Keep the Change: A Collector's Tales of Lucky Pennies, Counterfeit C-Notes, and Other Curious Currency Prolific author David Morrell tried something new when he wrote a period mystery in which the famous, opium-eating Victorian author Thomas De Quincey starred as the detective.

Prolific author David Morrell tried something new when he wrote a period mystery in which the famous, opium-eating Victorian author Thomas De Quincey starred as the detective.

In honor of St. Patrick's Day, we present an interview with Anne Enright, the inaugural Laureate for Irish Fiction and winner of the 2007 Man Booker Prize for The Gathering. Enright's next novel, The Green Road, is being published here by Norton on May 11.

In honor of St. Patrick's Day, we present an interview with Anne Enright, the inaugural Laureate for Irish Fiction and winner of the 2007 Man Booker Prize for The Gathering. Enright's next novel, The Green Road, is being published here by Norton on May 11. Can you describe your novel The Green Road?

Can you describe your novel The Green Road?