BEA Opener: Jonathan Franzen in Conversation

BookExpo America 2015 officially began at the Javits Center in New York City yesterday afternoon with an hour-long talk featuring Laura Miller, co-founder of Salon.com, and Jonathan Franzen, whose new novel, Purity (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), is due out September 1. Franzen fielded questions about his writing process, his love for his characters and the emotional work that went into writing Purity.

BookExpo America 2015 officially began at the Javits Center in New York City yesterday afternoon with an hour-long talk featuring Laura Miller, co-founder of Salon.com, and Jonathan Franzen, whose new novel, Purity (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), is due out September 1. Franzen fielded questions about his writing process, his love for his characters and the emotional work that went into writing Purity.

After Miller noted that Purity, a more plot-driven novel, is a bit of a departure from his recent books, Franzen responded: "I think the situation for the writer is that it gets harder to write novels, not easier, as time goes by." Writers, Franzen continued, typically use up the easier-to-write-about, "pretty close to the surface" things early on in their careers. As they dig deeper and deeper for subsequent books, it becomes harder to write about some of those subjects. He realized, he said, that a "certain kind of low-key realism" wasn't going to generate enough energy to "blow things open" and allow him to access that deeper, darker material. Stronger story formulations and more extreme situations, he said, helped him create that kind of energy.

|

|

| After the interview, Franzen signed for a long line of booksellers in the ABA lounge. | |

Miller wondered how much of Purity's plot Franzen had mapped out in advance and how much he discovered as he was writing. With plotting, Franzen asserted, it was easy to make a plan and then "as soon as you try to write it, you realize it's a bad plan." He recalled writing the first chapter of Purity easily, and then being stuck at that point for over a year.

"You have to wing it," he said. "If you don't wing it, it seems like it's written from an outline." He advised authors to "set yourself some impossible place to get to, and then it becomes kind of like an adventure."

Miller also noted a tension between Franzen's often-curmudgeonly, sometimes misanthropic public persona and the love that he professes to feel for his characters. Franzen said that he doesn't consider himself to be a misanthrope, and that "a thing is dead in the water until I can find some characters to love." He guessed that the perceived tension was between two imperatives, the first being that to make a book that really matters to someone it "has to have love in it," and the second being the writer's duty to tell the truth.

"We live in a world of received opinion and widely shared ideology," said Franzen. A writer who is "not satisfied with those sometimes simplistic ideologies" is going to be seen as hostile to the majority of people.

The conversation later turned to the book's title. The most obvious meaning has to do with the main character, a young woman named Purity. But, Franzen added, he wanted to examine the "notion of purity that informs fanatics of all kinds." And one of his goals in writing Purity was to write about youthful idealism. "When you're young, you can see things in very black-and-white terms," he continued, and purity can be something to aspire to, in the sense of being a pure artist, a pure writer or a pure activist. With the book Purity, he wanted to "write a book capacious enough to encompass that idealism and to see how it plays out, for better or for worse."

During the session's q&a portion, a woman who identified herself as a rising sophomore at the University of Connecticut said that she was working on a research project on Franzen's 2001 book The Corrections and the "depressed male protagonist in post-9/11 literature." She then appeared to ask Franzen her thesis question: How does the "depressed male character's identification and experience of his white masculinity relate to American society and culture in today's day and age?"

Noting the recent unrest in places like Ferguson, Mo., and Baltimore, Md., over the killing of young black men by police officers, Franzen said that "stuff we thought we should have been past a generation ago are still popping up," and that "unfortunately, white male power is rather alive and well.

"It takes a particularly anxious and damaged white male to fully embrace how problematic that makes it for a white male." --Alex Mutter

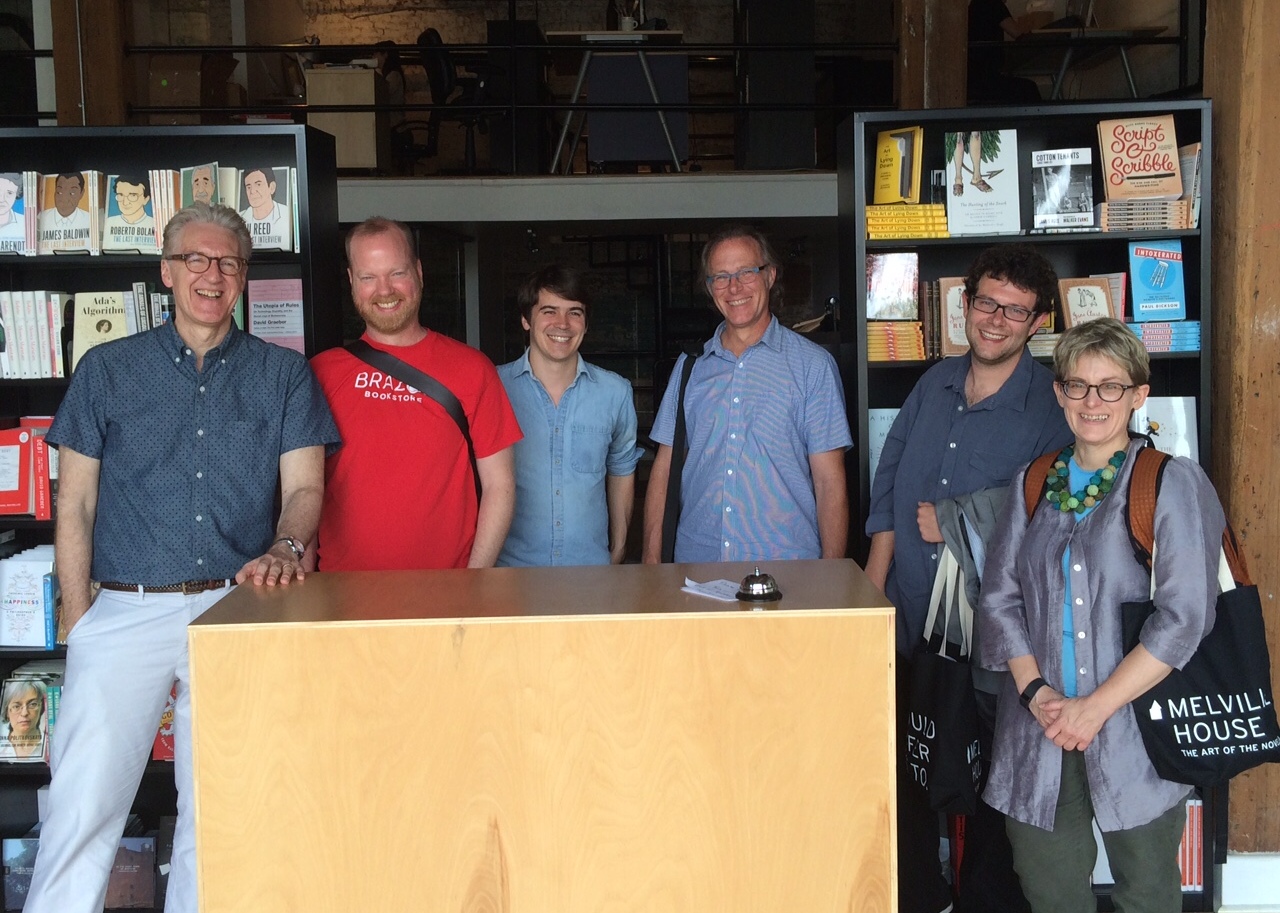

As part of Melville House's "Meet the Editors" program, a group of booksellers visited the publisher's office yesterday morning. Pictured, l.-r.: Melville House publisher Dennis Johnson; Jeremy Ellis, co-owner, Brazos Bookstore, Houston, Tex.; Melville digital media director Alex Shephard;, John Evans, co-owner, DIESEL Bookstore, Oakland, Larkspur and Brentwood, Calif.; Ben Rybeck, head of marketing, Brazos Bookstore; and bookseller Anmiryam Budner, Main Point Books, Bryn Mawr, Pa.

As part of Melville House's "Meet the Editors" program, a group of booksellers visited the publisher's office yesterday morning. Pictured, l.-r.: Melville House publisher Dennis Johnson; Jeremy Ellis, co-owner, Brazos Bookstore, Houston, Tex.; Melville digital media director Alex Shephard;, John Evans, co-owner, DIESEL Bookstore, Oakland, Larkspur and Brentwood, Calif.; Ben Rybeck, head of marketing, Brazos Bookstore; and bookseller Anmiryam Budner, Main Point Books, Bryn Mawr, Pa.

In the fourth quarter ended March 28, revenue at Indigo Books & Music rose 1%, to $186.2 million (about US$149.6 million) and the net loss improved slightly to $13.9 million ($11.2 million) from $14.4 million ($11.6 million) in the same period a year earlier. In the past year, the company closed eight stores. Indigo commented: "The improvement in earnings was a result of higher revenues, margin rate and lower operating expenses off-set by increased long-term incentive costs."

In the fourth quarter ended March 28, revenue at Indigo Books & Music rose 1%, to $186.2 million (about US$149.6 million) and the net loss improved slightly to $13.9 million ($11.2 million) from $14.4 million ($11.6 million) in the same period a year earlier. In the past year, the company closed eight stores. Indigo commented: "The improvement in earnings was a result of higher revenues, margin rate and lower operating expenses off-set by increased long-term incentive costs."

Later this summer, Kobo is launching what it calls the eRead Local program for American Booksellers Association members to encourage store customers to try e-reading. For each new Kobo customer they sign up, ABA members will receive $5, while each new customer who creates a Kobo account through an affiliate ABA member will receive a $5 credit toward their first e-book purchase. The program will run for 100 days.

Later this summer, Kobo is launching what it calls the eRead Local program for American Booksellers Association members to encourage store customers to try e-reading. For each new Kobo customer they sign up, ABA members will receive $5, while each new customer who creates a Kobo account through an affiliate ABA member will receive a $5 credit toward their first e-book purchase. The program will run for 100 days. In a story about independent bookstores making a comeback, Flossie McNabb, who operates

In a story about independent bookstores making a comeback, Flossie McNabb, who operates  Inc. magazine asked five businesses "to share their experiences employing autistic people and the

Inc. magazine asked five businesses "to share their experiences employing autistic people and the  The Ultimate Disney Party Book: 8 Fantastic Disney Themes, Over 65 Recipes and Crafts for the Perfect Party

The Ultimate Disney Party Book: 8 Fantastic Disney Themes, Over 65 Recipes and Crafts for the Perfect Party

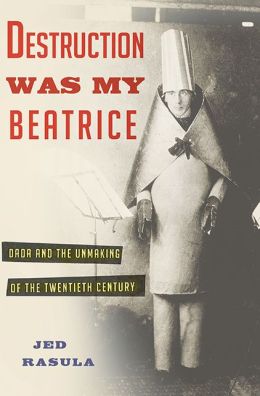

The title of Jed Rasula's insightful contribution to art history, Destruction Was My Beatrice: Dada and the Unmaking of the Twentieth Century, comes from an 1867 letter written nearly 50 years before Dadaism was born by the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé to describe his poetic muse (à la Dante's heavenly guide) inspiring him to write poetry that flames up only to burn itself out--art out of destruction.

The title of Jed Rasula's insightful contribution to art history, Destruction Was My Beatrice: Dada and the Unmaking of the Twentieth Century, comes from an 1867 letter written nearly 50 years before Dadaism was born by the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé to describe his poetic muse (à la Dante's heavenly guide) inspiring him to write poetry that flames up only to burn itself out--art out of destruction.