Shelf Awareness continues a multi-part series on how booksellers are reacting to a range of laws boosting the minimum wage that have been enacted in various states and municipalities around the country. Last week and this week, we examined how booksellers in California, Washington, D.C., and New York are dealing with new state and local wage requirements. Today, in our last installment of this series, we talk with booksellers in Seattle, Wash.

In Seattle, the current minimum wage for employees who are not receiving benefits at companies with fewer than 500 employees is $12 per hour. For employees at companies with fewer than 500 employees who are receiving benefits, the wage is $10.50 per hour. For the former group, the wage will reach $15 per hour by January 1, 2019, while the latter will arrive at that level by January 1, 2021. Once employers reach $15 per hour, the wage will increase each year by a percentage pegged to the Consumer Price Index.

At University Book Store, which has three locations within Seattle proper and four in surrounding municipalities, payroll costs have increased by nearly 6% in the last fiscal year. According to Pam Cady, manager of the general book department, and Lara Konick, chief of retail operations, this is the result not only of raising wages at the bottom of the pay scale but also of raising wages for those who were already "ahead of the curve." Employees at UBS locations outside the city are being paid commensurate to those in the Seattle.

At University Book Store, which has three locations within Seattle proper and four in surrounding municipalities, payroll costs have increased by nearly 6% in the last fiscal year. According to Pam Cady, manager of the general book department, and Lara Konick, chief of retail operations, this is the result not only of raising wages at the bottom of the pay scale but also of raising wages for those who were already "ahead of the curve." Employees at UBS locations outside the city are being paid commensurate to those in the Seattle.

"The cities surrounding us are looking at Seattle and will probably be heading in that direction soon," said Cady. Tracking pay location by location would be more complicated than it's worth, she added, and asking employees outside of Seattle to be paid less for the same amount of work simply wouldn't be fair.

Konick, meanwhile, said she was very concerned about the effects that wage compression might have on staff. Wages are being forced up from the bottom by minimum wage increases, she explained, but given books' extremely thin margins, there is effectively a ceiling. As a result, wages are being compressed toward the middle. For example, by next January, she noted, a starting cashier will make $13 per hour, which is what some people who have been working at UBS for five or six years are currently earning. Said Konick: "There becomes less and less incentive for anyone to stay for a long period of time."

Cady and Konick hope to avoid layoffs, and are looking for ways to work more efficiently and effectively, as well as to leverage things the store is already doing without significantly increasing payroll. For example, UBS already does a small amount of business-to-business sales. Although growing that area would take time and effort, it could have a potentially high sales impact with a low payroll consequences. A new inventory management system is also in the works.

Konick also noted that removing prices from books might work to the disadvantage of bookstores. She explained: "If there were no prices on books, the perceived value would be whatever the lowest price [customers] could find is."

"On a day-to-day basis, we're figuring it out so far," said Cady. "People are not leaving. There have been challenges for years."

In the first six months of 2016, sales at Seattle's Elliott Bay Book Company have risen more than 10%. Peter Aaron, the owner of the store, cautioned that there is no way to know if there's a causative relationship between the sales increase and the minimum wage increase or if it's simply a coincidence, but he emphasized that so far, he has seen no negative financial consequences of the higher minimum wage.

In the first six months of 2016, sales at Seattle's Elliott Bay Book Company have risen more than 10%. Peter Aaron, the owner of the store, cautioned that there is no way to know if there's a causative relationship between the sales increase and the minimum wage increase or if it's simply a coincidence, but he emphasized that so far, he has seen no negative financial consequences of the higher minimum wage.

In order to maintain "fairness and proportionality" between those who have been at the store for a long time and those who are just walking in the door, Elliott Bay has raised employee pay "up and down the line," Aaron said. The costs associated with these increases are not insignificant, but the store is taking it one year at a time.

One possible negative consequence that the store has seen--though Aaron also stressed that a causative relationship with the wage increase can't be shown--is that it has lately been difficult to hire new staff. Aaron suggested that this may be a result of Seattle's strong economy.

"It's a cyclical thing," Aaron said. "There are times when the overall economy is not doing that well and all kinds of people are looking to work for the kinds of wages that a bookstore can afford to pay. And there are times when things are booming and it's hard to hire people."

While Aaron said he hoped that publishers might unveil programs that help bookstore profitability, he was strongly against the idea of removing prices from books. With book pricing, he said, there is only pressure from the bottom. Publisher-set prices maintain some order. Without them, he said, it's "just chaos."

On the whole, Aaron was extremely supportive of raising the minimum wage. "Based on my experience it looks like a win-win. I think it's a great thing." --Alex Mutter

SHELFAWARENESS.0213.S4.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

Moleskin has launched

Moleskin has launchedSHELFAWARENESS.0213.T3.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

At

At  In the first six months of 2016, sales at Seattle's

In the first six months of 2016, sales at Seattle's

Congratulations to

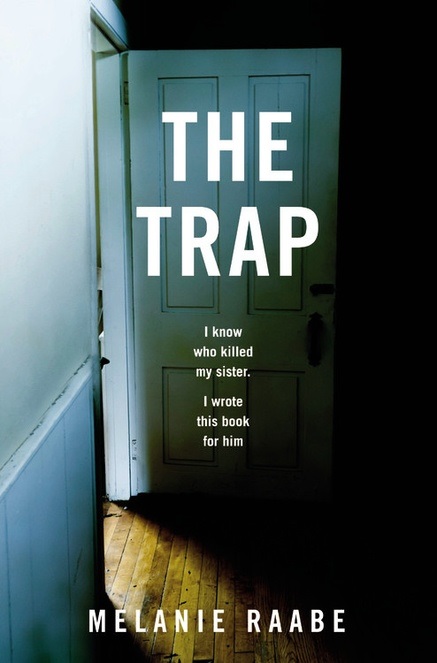

Congratulations to  The GBO described the book this way: "Successful novelist Linda Conrads has not left her house for more than a decade. She is haunted by the past: twelve years ago, she found her younger sister stabbed to death, lying in a pool of blood. The murder case was never solved. Traumatized, Linda seals herself off from society; the only means left to communicate to the outside world is her writing. When she recognizes her sister's murderer on TV--it is a renowned journalist--she sets an irresistible 'literary' trap: she writes a novel about her sister's death and invites him home for an exclusive interview."

The GBO described the book this way: "Successful novelist Linda Conrads has not left her house for more than a decade. She is haunted by the past: twelve years ago, she found her younger sister stabbed to death, lying in a pool of blood. The murder case was never solved. Traumatized, Linda seals herself off from society; the only means left to communicate to the outside world is her writing. When she recognizes her sister's murderer on TV--it is a renowned journalist--she sets an irresistible 'literary' trap: she writes a novel about her sister's death and invites him home for an exclusive interview." How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life

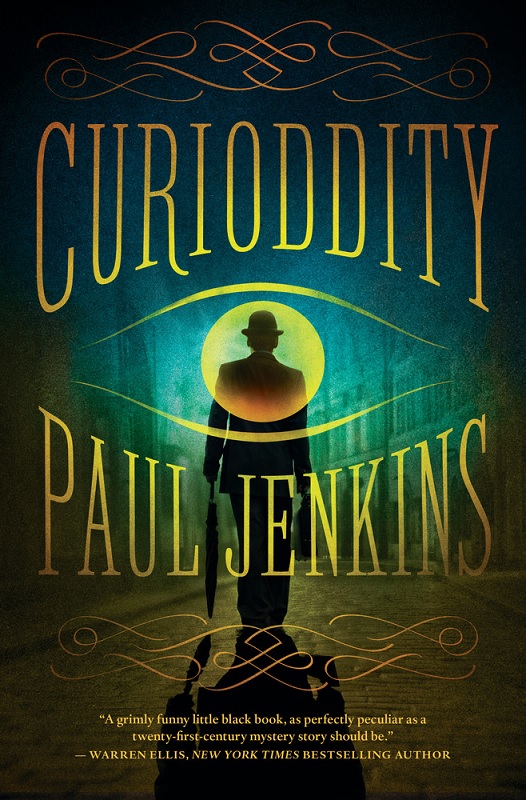

In Wil Morgan's life, ordinary events in a dull environment are the norm. His job as a private investigator specializing in divorce and insurance fraud gives him little joy or money to pay his bills. The people he interacts with on a daily basis do nothing to make his life more memorable. And for years, he's lied to his father about his work, telling him he's an accountant, which only adds to the gloom in Wil's life. On his daily trudge to work, past the giant billboard of Marcus James, "national TV personality of no apparent talent who nevertheless possessed the ability to persuade millions of people to part with something useful in exchange for something useless, usually in three or four easy payments," Wil's only moments of pleasure are when he allows himself to reminisce about his childhood and his mother, who was able to show him the magic in everything. But Melinda Morgan died when Wil was 10, and with her died Wil's ability to see the world in a different light. That is, until Mr. Dinsdale, curator of the Curioddity Museum, appears in his office to hire him to search for a box of levity (the opposite of gravity) that has gone missing from its exhibit in the museum. Wil accidentally discovers the box in a junk shop, landing a first date with the eccentric proprietress at the same time, before quickly moving on to solve another case at the museum. Over the course of just a week's time, Wil discovers far more than he ever imagined as he sleuths his way through a new and intriguing existence.

In Wil Morgan's life, ordinary events in a dull environment are the norm. His job as a private investigator specializing in divorce and insurance fraud gives him little joy or money to pay his bills. The people he interacts with on a daily basis do nothing to make his life more memorable. And for years, he's lied to his father about his work, telling him he's an accountant, which only adds to the gloom in Wil's life. On his daily trudge to work, past the giant billboard of Marcus James, "national TV personality of no apparent talent who nevertheless possessed the ability to persuade millions of people to part with something useful in exchange for something useless, usually in three or four easy payments," Wil's only moments of pleasure are when he allows himself to reminisce about his childhood and his mother, who was able to show him the magic in everything. But Melinda Morgan died when Wil was 10, and with her died Wil's ability to see the world in a different light. That is, until Mr. Dinsdale, curator of the Curioddity Museum, appears in his office to hire him to search for a box of levity (the opposite of gravity) that has gone missing from its exhibit in the museum. Wil accidentally discovers the box in a junk shop, landing a first date with the eccentric proprietress at the same time, before quickly moving on to solve another case at the museum. Over the course of just a week's time, Wil discovers far more than he ever imagined as he sleuths his way through a new and intriguing existence.