Marley was dead: to begin with.

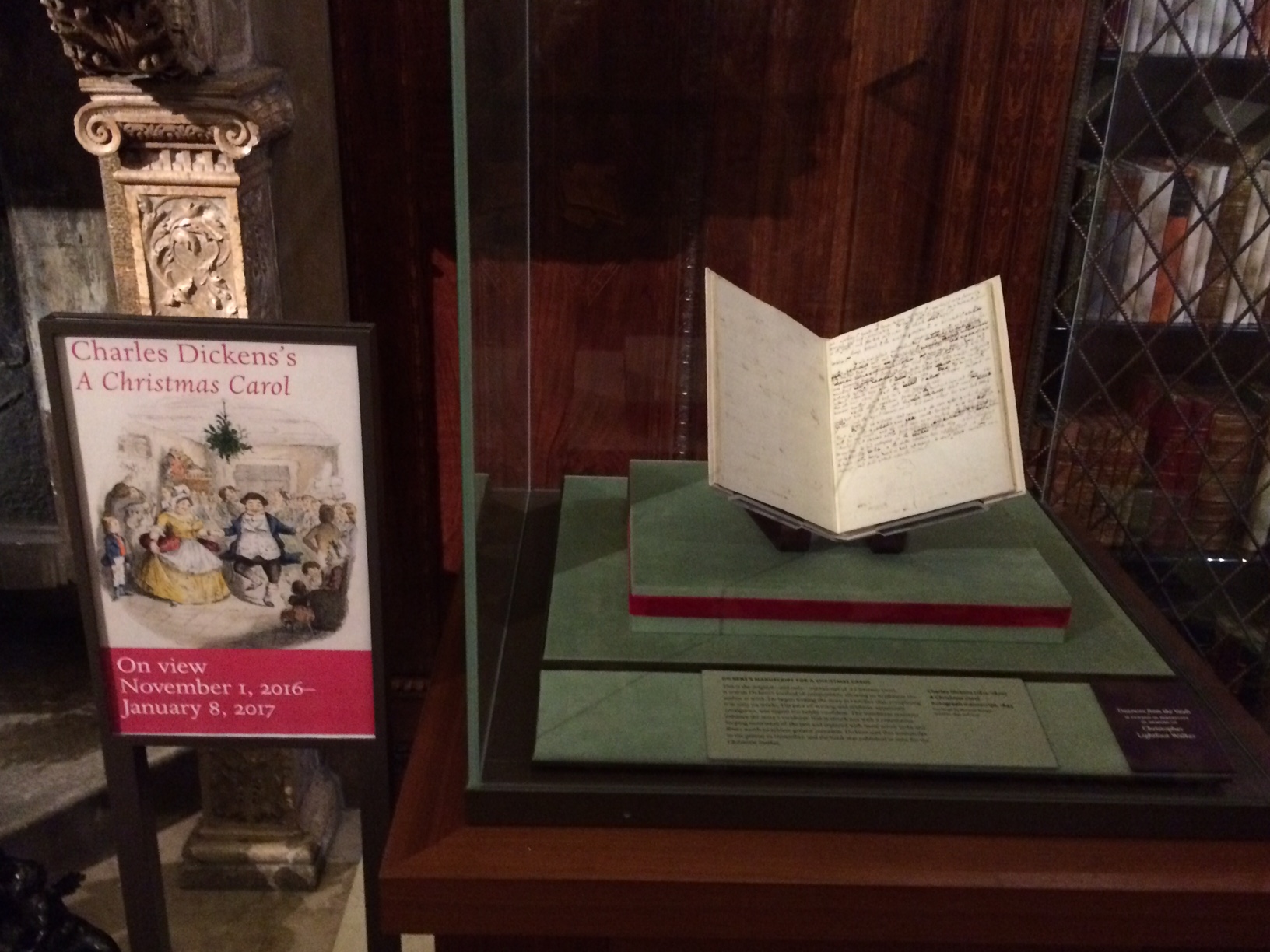

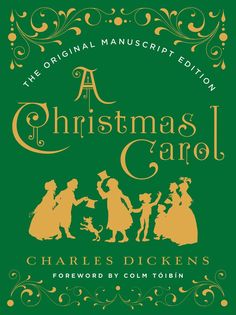

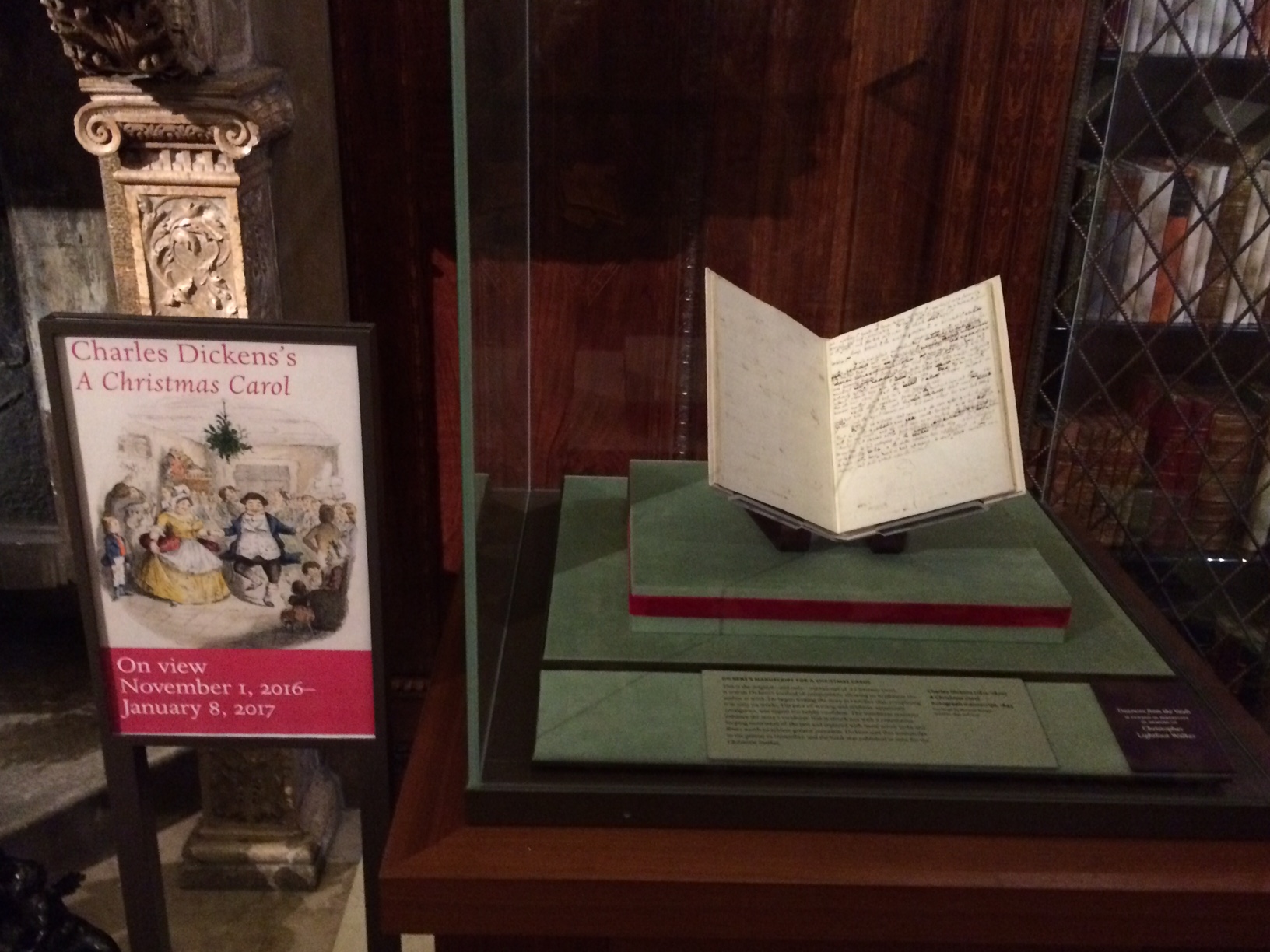

It is one of my favorite opening lines in literature, though I hadn't read the classic holiday season tale by Charles Dickens in years, perhaps decades. Recently, however, I was inspired to revisit his world by 1) the publication last month of the fascinating A Christmas Carol: The Original Manuscript Edition (Norton), with a foreword by Colm Tóibín; and 2) a visit to the Morgan Library & Museum in Manhattan last week, where the treasure itself--the one-of-a-kind manuscript--is displayed every year in Pierpont Morgan's paradisiacal library.

I'll admit, however, that my bookseller's soul was also touched (perhaps just a little Scrooge-like) when I learned about the Dickensian path this unique document took to reach its hallowed place under glass, near a monumental fireplace tastefully decorated with green garland and red ribbon. In his introduction to the new facsimile edition, Declan Kiely chronicles the book's journey to its recent meeting with me (well, not quite that detailed) as I sat for a long time on a cushioned bench, communing (not too strong a word, as it turned out) with an open book, its legacy and its ghosts.

I'll admit, however, that my bookseller's soul was also touched (perhaps just a little Scrooge-like) when I learned about the Dickensian path this unique document took to reach its hallowed place under glass, near a monumental fireplace tastefully decorated with green garland and red ribbon. In his introduction to the new facsimile edition, Declan Kiely chronicles the book's journey to its recent meeting with me (well, not quite that detailed) as I sat for a long time on a cushioned bench, communing (not too strong a word, as it turned out) with an open book, its legacy and its ghosts.

After the printers had done their work in 1843, Dickens arranged for the loose manuscript pages to be bound in red morocco as a gift for his solicitor, friend and creditor Thomas Mitton. Five years after the author's death, in 1875, Mitton sold the manuscript for £50 (about $62) to Francis Harvey, a London bookseller who quickly found an eager buyer in Henry George Churchill, a private collector. Churchill decided to sell it in 1882 to a bookseller in Birmingham, where "crowds reportedly gathered there for an opportunity to view the manuscript before it was sold for £200 to the London booksellers Robson and Kerslake," Kiely writes. Soon after, Stuart M. Samuel purchased it for £300 as an investment, then he sold it in 1890 to London booksellers J. Pearson & Co. for £1,000.

And now the retail plot reaches its final chapter. Sometime before 1900, Pierpont Morgan acquired the manuscript from Pearson. After his death in 1913, he bequeathed it to J.P. Morgan Jr., who subsequently established the Morgan Library in his father's honor.

On December 12, 1923, the New York Times reported: "Among the various kinds of riches in the Morgan Library on East Thirty-sixth Street, there is, kept very carefully, a particular treasure. It is not very old and it is not at all beautiful, but it is a very significant possession, for which its owner paid a high price, and on which he sets a high value. It is written in a well-known, scratchy hand--on sheets of yellowing paper, the manuscript of Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol....

On December 12, 1923, the New York Times reported: "Among the various kinds of riches in the Morgan Library on East Thirty-sixth Street, there is, kept very carefully, a particular treasure. It is not very old and it is not at all beautiful, but it is a very significant possession, for which its owner paid a high price, and on which he sets a high value. It is written in a well-known, scratchy hand--on sheets of yellowing paper, the manuscript of Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol....

"Mr. Morgan's original manuscript is, of course, a well-nigh priceless treasure. And it is so less because it is the writing of a great work by a great novelist than because it is, in its genuineness and its intimacy, something that for nearly three-quarters of a century has been part of the thought of Christmas cheer, and that throughout the English-speaking world men and women and little children have loved."

As I communed in the library, I thought about this book as both a singular art object as well as the original container for a story that has been told worldwide for nearly two centuries, spawning myriad editions, illustrations and film/TV/stage adaptations. A Christmas Carol is a fundamental tale we share again and again, hoping to learn something new, or at least to remind ourselves of an important lesson about being human that seemed so obvious when we were children.

We... tend to forget.

The Morgan displays its bound manuscript open to just a single page. This year it is the end of Stave I. After his frightening encounter with Jacob Marley's ghost and the promise of more terrors to come, Scrooge watches the specter float away to join "the mournful dirge" outside. (Apparently "dirge" was not a frightening enough word for Dickens. You can see his insertion of the adjective "mournful" on the page.) Scrooge looks out of his bedroom window and sees:

The air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste, and moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Marley's Ghost; some few (they might be guilty governments) were linked together; none were free. Many had been personally known to Scrooge in their lives. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost, in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron safe attached to its ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below, upon a door-step. The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.

When the vision ceases, Scrooge attempts to say 'Humbug!' but stops at the first syllable. His redemptive journey has begun.

When the vision ceases, Scrooge attempts to say 'Humbug!' but stops at the first syllable. His redemptive journey has begun.

In a foreword to the facsimile edition, Colm Tóibín observes: "The word dream has been transformed, has been taken from its dark, cold, lonely, fearful place and, instead of being a watchword for frightful imaginings, filled with mockery and unbearable visions, has come to mean an opening of the self, a way of reimagining the world. And so, with that change, from nightmare to sweet reality, from miserliness to giving, from misery to merriness, Christmas came into being. Courtesy of Dickens, we live in its shadow still and on one cheery, idealized day of the year, as we force Scrooge to appear as merely a distant warning to us all, we become the happy, jolly Cratchits."

'Tis that season: to begin with.

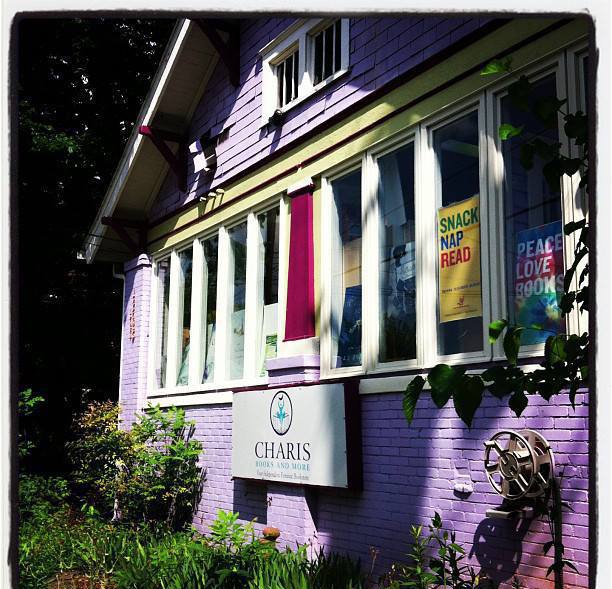

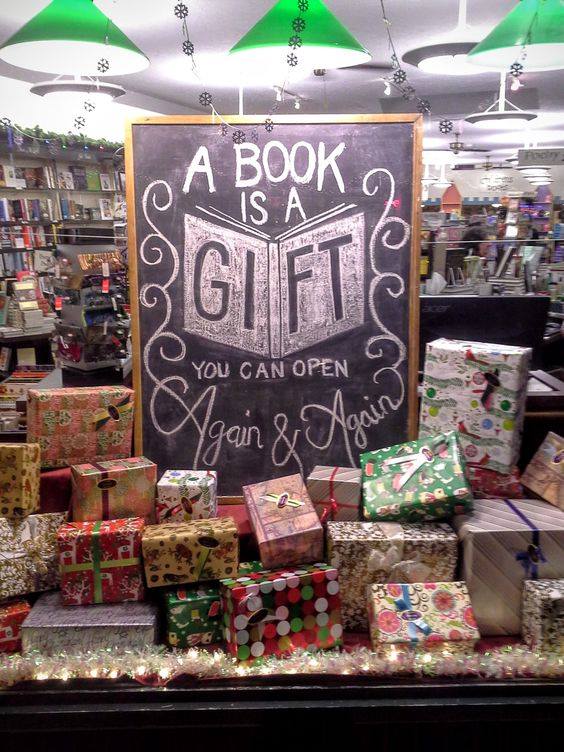

"This is a happy story, not just for Billings, but also for brick-and-mortar bookstores in general. In the wake of the Amazon and e-book revolutions, people have begun seeking a more personal experience, a trend that is reshaping the marketplace. The secret sauce is a bookstore that answers only to its community. It refreshes the human spirit in a fundamental way. This House of Books is that kind of gift, from the people to the people."

"This is a happy story, not just for Billings, but also for brick-and-mortar bookstores in general. In the wake of the Amazon and e-book revolutions, people have begun seeking a more personal experience, a trend that is reshaping the marketplace. The secret sauce is a bookstore that answers only to its community. It refreshes the human spirit in a fundamental way. This House of Books is that kind of gift, from the people to the people."

As part of his Holiday Bookstore Bonus Program,

As part of his Holiday Bookstore Bonus Program,

Feminist bookstore

Feminist bookstore

On Tuesday, Ingram Content Group hosted many clients and friends to celebrate the opening of its new, 9,800-square-foot offices near Bryant Park in New York City, with space for staff from Perseus's distribution businesses that Ingram bought earlier this year. Pictured: Ingram associates cut the ribbon on the new space: (l.-r.) Edison Garcia, Kelly Gallagher, Michael Rentas, Diana Ribeiro, Sabrina McCarthy and Zoya Khera.

On Tuesday, Ingram Content Group hosted many clients and friends to celebrate the opening of its new, 9,800-square-foot offices near Bryant Park in New York City, with space for staff from Perseus's distribution businesses that Ingram bought earlier this year. Pictured: Ingram associates cut the ribbon on the new space: (l.-r.) Edison Garcia, Kelly Gallagher, Michael Rentas, Diana Ribeiro, Sabrina McCarthy and Zoya Khera. From the

From the  While visiting Atlanta, Ga., recently to promote his new film, Fences,

While visiting Atlanta, Ga., recently to promote his new film, Fences,  Jill A. Tardiff is the manager and buyer at Lucy's Whey Artisanal Cheese at Chelsea Market in New York City. She is a member of the American Cheese Society and serves on its member services committee. Tardiff is the

Jill A. Tardiff is the manager and buyer at Lucy's Whey Artisanal Cheese at Chelsea Market in New York City. She is a member of the American Cheese Society and serves on its member services committee. Tardiff is the  Luck has a way of following Piet Barol wherever he goes--until now. The debonair young libertine introduced in

Luck has a way of following Piet Barol wherever he goes--until now. The debonair young libertine introduced in

I'll admit, however, that my bookseller's soul was also touched (perhaps just a little Scrooge-like) when I learned about the Dickensian path this unique document took to reach its hallowed place under glass, near a monumental fireplace tastefully decorated with green garland and red ribbon. In his introduction to the new facsimile edition, Declan Kiely chronicles the book's journey to its recent meeting with me (well, not quite that detailed) as I sat for a long time on a cushioned bench, communing (not too strong a word, as it turned out) with an open book, its legacy and its ghosts.

I'll admit, however, that my bookseller's soul was also touched (perhaps just a little Scrooge-like) when I learned about the Dickensian path this unique document took to reach its hallowed place under glass, near a monumental fireplace tastefully decorated with green garland and red ribbon. In his introduction to the new facsimile edition, Declan Kiely chronicles the book's journey to its recent meeting with me (well, not quite that detailed) as I sat for a long time on a cushioned bench, communing (not too strong a word, as it turned out) with an open book, its legacy and its ghosts. On December 12, 1923, the New York Times reported: "Among the various kinds of riches in the Morgan Library on East Thirty-sixth Street, there is, kept very carefully, a particular treasure. It is not very old and it is not at all beautiful, but it is a very significant possession, for which its owner paid a high price, and on which he sets a high value. It is written in a well-known, scratchy hand--on sheets of yellowing paper, the manuscript of Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol....

On December 12, 1923, the New York Times reported: "Among the various kinds of riches in the Morgan Library on East Thirty-sixth Street, there is, kept very carefully, a particular treasure. It is not very old and it is not at all beautiful, but it is a very significant possession, for which its owner paid a high price, and on which he sets a high value. It is written in a well-known, scratchy hand--on sheets of yellowing paper, the manuscript of Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol.... When the vision ceases, Scrooge attempts to say 'Humbug!' but stops at the first syllable. His redemptive journey has begun.

When the vision ceases, Scrooge attempts to say 'Humbug!' but stops at the first syllable. His redemptive journey has begun.