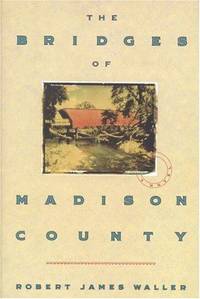

"The reality is not exactly what the song started out to be, but it's not a bad song." --Robert James Waller, The Bridges of Madison County

Before I became a bookseller, I never saw myself as the kind of guy who would fall prey to "the book everybody's reading." And yet, lurking in my past were certain signs of weakness--Erich Segal's Love Story and Richard Bach's Jonathan Livingston Seagull come to mind. These I read moments after they exploded on the scene, but I quickly backed away from the damning evidence.

|

| Robert James Waller |

Distancing myself from books that become huge bestsellers is probably a minor weakness, but memory occasionally serves up discomforting reminders. This happened last weekend when I learned that Robert James Waller had died. First I felt bad about his passing, then my brain cells conjured up an unnerving recollection of my introduction to his mega-bestselling novel, The Bridges of Madison County.

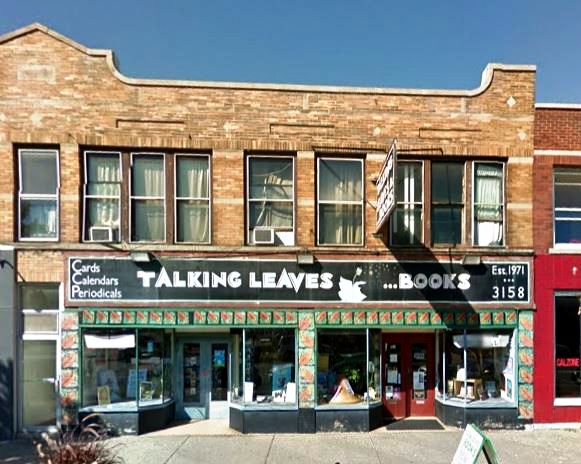

Here's a little trade secret. Sometimes booksellers like a book until everybody else does, and then they have second thoughts. In the spring of 1992, when Bridges was published, I had just started working as a bookseller. There was some early buzz about this title, though without social media the volume was relatively low. Still, I read it; thought it was okay. In fact, I liked it more than I'd expected to, and some of my bookselling colleagues were raving about it.

By late summer, Bridges was a genuine phenomenon, beginning an epic three-year run on the New York Times bestseller list. I didn't have to praise the novel in order to sell it. I could practically hand it to anyone who came through the bookstore's front door and then ask, "Anything else?" They would say no, and rush away to devour the story. I was tired of the book, but it didn't need me anyway.

A year later, noting that Bridges had gone through 41 printings, with 2.9 million copies in print and 150,000 new copies being sold weekly, the New York Times wrote: "It was rebuffed by some bookstore chains, treated most unkindly in a number of reviews, and scoffed at by the publishing elite in New York City, where one quite bitter editor recently said, 'People buy it for the same reason they would buy a Mother's Day card.' But who cares?"

A year later, noting that Bridges had gone through 41 printings, with 2.9 million copies in print and 150,000 new copies being sold weekly, the New York Times wrote: "It was rebuffed by some bookstore chains, treated most unkindly in a number of reviews, and scoffed at by the publishing elite in New York City, where one quite bitter editor recently said, 'People buy it for the same reason they would buy a Mother's Day card.' But who cares?"

Who cares, indeed. By then, I'd learned how to handsell Bridges without being dismissive. Bookselling, it turned out, was a lot more complicated than just waving books I loved around and saying, "You've got to read this!"

Booksellers sometimes handsell books they haven't read. They handsell books they don't even like much. This is not, usually, a sin of intention. No one wants to handsell a "bad" book. It is, at worst, a sin of omission. What you refrain from saying to a customer during a conversation about a particular title can be as important as what you do say.

Booksellers routinely discuss not-so-great books with customers who love those titles passionately and are seeking comparable works. By "not-so-great," I mean books that we've dismissed for any number of objective, subjective and even irrational reasons. This can include works that are well-reviewed, popular, award-winning, or any combination of the three.

And every bookseller has had this reaction while reading an ARC: "I'm not crazy about this book, but it's going to be really easy to handsell." Conversely, there are books you love that you'd struggle to handsell at a 100% discount.

A bookseller's job description is to express--or withhold--judgment depending upon the situation. Sometimes you walk a conversational high wire. Nodding and smiling help; saying "a lot of people liked that one" or "he's very popular" or "it's been getting good reviews" will get you through as well. A personal favorite, which I leaned on more than a few times, was that a particular author "knows his (or her) audience well and writes with them in mind."

If you are feeling pressured for your opinion on a book you just don't like, may I prescribe a small dose of retail therapy from the movie Caddyshack. Al Czervic (Rodney Dangerfield) bursts into a posh country club's pro shop and starts buying everything in sight. He notices a garish hat on display and says, "This is the worst lookin' hat I ever saw." Then he spots the club's president, Judge Smails (Ted Knight), standing nearby, wearing the same hat, and adds: "Oh, it looks good on you, though."

Welcome to the world of handselling, where you sometimes just have to smile and say the bookseller's equivalent of "Oh, it looks good on you, though."

Is that wrong? Absolutely not. In fact, it is a kind of bibliodiplomacy. You want customers to be comfortable with their choices. You don't want them to feel judged. You hope they walk away from a handselling conversation thinking, "That was fun." Well, to be honest, You want them to walk away with a huge stack of new books, thinking, "That was fun."

Thanks for the early lesson, Mr. Waller. R.I.P.

"Whenever I was encouraged by my elders to pick up a book, I was often told, 'Read so as to know the world.' And it is true; books have invited me into different countries, states of mind, social conditions and historical epochs; they have offered me a place at the most unusual gatherings....

"Whenever I was encouraged by my elders to pick up a book, I was often told, 'Read so as to know the world.' And it is true; books have invited me into different countries, states of mind, social conditions and historical epochs; they have offered me a place at the most unusual gatherings....

Despite significant challenges, booksellers in the U.K. had "a pretty good year," Tim Godfray, CEO of the

Despite significant challenges, booksellers in the U.K. had "a pretty good year," Tim Godfray, CEO of the

An SRO crowd came to

An SRO crowd came to  Posted on Facebook by

Posted on Facebook by  Effective June 5, Diamond Comic Distributors will handle exclusive sales and distribution for

Effective June 5, Diamond Comic Distributors will handle exclusive sales and distribution for  The Accelerators Volume 1: Time Games

The Accelerators Volume 1: Time Games Winners of the

Winners of the

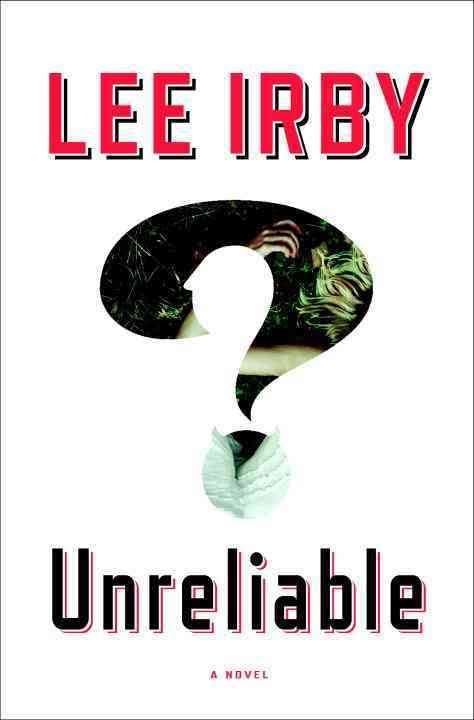

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for: In a viciously delicious thriller, Lee Irby (The Van) introduces a charming, refined protagonist who could be a monster, a deranged jilted lover or simply one of love's losers. From beginning to end, the only reliable truth is that the narrator is a liar.

In a viciously delicious thriller, Lee Irby (The Van) introduces a charming, refined protagonist who could be a monster, a deranged jilted lover or simply one of love's losers. From beginning to end, the only reliable truth is that the narrator is a liar.

A year later, noting that Bridges had gone through 41 printings, with 2.9 million copies in print and 150,000 new copies being sold weekly, the New York Times wrote: "It was rebuffed by some bookstore chains, treated most unkindly in a number of reviews, and scoffed at by the publishing elite in New York City, where one quite bitter editor recently said, 'People buy it for the same reason they would buy a Mother's Day card.' But who cares?"

A year later, noting that Bridges had gone through 41 printings, with 2.9 million copies in print and 150,000 new copies being sold weekly, the New York Times wrote: "It was rebuffed by some bookstore chains, treated most unkindly in a number of reviews, and scoffed at by the publishing elite in New York City, where one quite bitter editor recently said, 'People buy it for the same reason they would buy a Mother's Day card.' But who cares?"