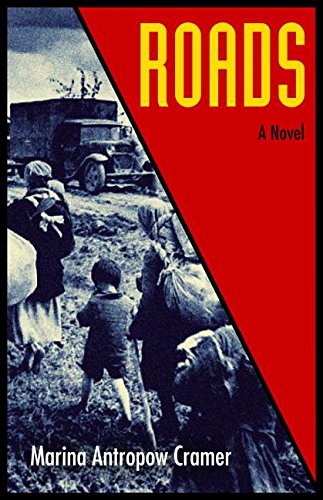

For Marina Antropow Cramer, the publication on May 1 of her first novel, Roads, by the Academy Chicago imprint of the Chicago Review Press, "still feels unreal," she says. "It still feels like this is happening to someone else."

For Marina Antropow Cramer, the publication on May 1 of her first novel, Roads, by the Academy Chicago imprint of the Chicago Review Press, "still feels unreal," she says. "It still feels like this is happening to someone else."

One might think that for Cramer, because of her bookselling background, publishing a book would be more familiar than for most new authors: for 17 years, she owned Cup & Chaucer Bookstore in Montclair, N.J., then for 12 years after that, she was a bookseller at Watchung Booksellers, also in Montclair.

"Being on the other side of the counter, so to speak, even though I know what happens over there, has been a revelation and an education," she says. One example is the letter she is sending to bookstores and libraries seeking to arrange appearances, something she has put great care into. "I've read a lot of these letters and know how easily they get overlooked," she remembers. And the editing process was "a little painful," she says. "But a better book came out of it."

Her bookselling experience was important for the writing of Roads, Cramer says. "Going to work and being in an environment that's all about books was something that fed me. Handling books all the time, talking with people about books, arranging books, shelving books, meeting with writers and editors and agents and serious readers. I don't know if I could have this without that."

She had experience in general retail before setting up a bookstore, which she found much more satisfying because "with books, you're dealing with stories and ideas and history and all the wonderful things books deal with. It matters what book you put in people's hands. Books are not interchangeable. They're a big part of my life, and I couldn't have done this without having done that."

Roads, the story of a Russian family living in Yalta, in the Crimea, begins in the late 1930s, when life under Stalin has many challenges; some people go along with the regime while others continue to find sustenance in the old ways. Then the Nazis invade. As the occupation becomes increasingly difficult, the main characters--an older couple, their young daughter, and the daughter's husband--volunteer for agricultural work in Germany so that they can stay together--and be treated better than the many Russians who are being picked up in the streets and sent to Nazi labor camps. In Germany, they find they were lied to--but they survive appalling conditions and just miss being caught in the firebombing of Dresden in 1945. But as the war comes to its bloody conclusion, they're separated and, after the German surrender search for each other amid the chaos of postwar Germany--while needing to avoid the Red Army and allies who might return them to a grim fate in the Soviet Union. The characters are strongly drawn and fascinating, from the young dreamer Filip to his formidable mother-in-law, Ksenia, who cares for the family in a variety of ways--from finding and preparing food to providing the kind of grounding and clearsightedness needed to survive a string of harrowing situations.

Roads, the story of a Russian family living in Yalta, in the Crimea, begins in the late 1930s, when life under Stalin has many challenges; some people go along with the regime while others continue to find sustenance in the old ways. Then the Nazis invade. As the occupation becomes increasingly difficult, the main characters--an older couple, their young daughter, and the daughter's husband--volunteer for agricultural work in Germany so that they can stay together--and be treated better than the many Russians who are being picked up in the streets and sent to Nazi labor camps. In Germany, they find they were lied to--but they survive appalling conditions and just miss being caught in the firebombing of Dresden in 1945. But as the war comes to its bloody conclusion, they're separated and, after the German surrender search for each other amid the chaos of postwar Germany--while needing to avoid the Red Army and allies who might return them to a grim fate in the Soviet Union. The characters are strongly drawn and fascinating, from the young dreamer Filip to his formidable mother-in-law, Ksenia, who cares for the family in a variety of ways--from finding and preparing food to providing the kind of grounding and clearsightedness needed to survive a string of harrowing situations.

Cramer's writing is lush and poetic with a refreshing edge. Just when some of the characters seem to be familiar, they do or say something significant that surprises the reader and puts everything that has happened before in a new light--and leads down a new road. Throughout Roads, the family takes a variety of roads, from literal to emotional to developmental. In different ways, Cramer says, her characters "get from one place to another in their lives."

Cramer's own family had a similar background to those of the main characters in her novel. They lived in Yalta, then worked in German labor camps, before living for a time in Belgium and finally emigrating to the U.S. Cramer was born in postwar Germany and was nine when the family moved here.

"Roads has elements of my family history in it," she says, "but it's not the story of my family." She took parts of her family's history, parts from others who went through the similar experiences, and "made some things up." She emphasizes that the characters are composite and that she doesn't appear in the book.

For Cramer, the crux of the story is the immigrant experience, which she was drawn to increasingly over time, especially after her grandmother died, when, she says, "I started thinking about where I came from."

That interest led her to focus on the key problem faced by immigrants who move under duress and is common "wherever there's military conflict or environmental upheavals": "knowing you have to go, and all that you can take with you has to fit in maybe two suitcases and that you won't come back. How would you decide what to take? How do you start on that road and deal with not coming back?"

And once a person takes that road, it raises other questions, Cramer says. "What is home? Where do you belong if you can't be there? Who are you?" As an immigrant herself, Cramer said she knew "the sense of displacement" when she traveled to the U.S. at age nine. "It didn't feel right. It didn't feel like the place I belonged." She thought she might feel a sense of belonging in Europe, but when she visited as an adult, while she thought it "very nice," she didn't feel she belonged there, either. "There's always that sense of displacement and not knowing where you belong. I don't think that goes away."

It didn't go away for her mother either, Cramer says, who has been in the U.S. for 60 years and still says things like, "Americans! Why do they smile so much?"

Cramer's mother, who will turn 91 in April, is "astute and cryptic" about Roads, Cramer says. She told her mother repeatedly that she was writing a work that has roots in family lore, but her mother focused on this only once, asking, "Did you tell the truth?" Cramer still is not sure how to take the question: "I don't know if she meant, 'You didn't tell the truth, did you?' or if she meant I should tell the truth."

Cramer had to travel down other roads before the subject fully engaged her. At first, she says, "I wasn't interested. I had been hearing the family history since I was born and thought, 'Okay, all right. The war is over, let's talk about something else.' "

Cramer wrote the book over 15 years, writing parts of it out of sequence. At one point, she spread out the parts she had written on a table, and saw where the gaps were. "It was a very visual assessment of where the work was and what needed to get filled in." She also traveled to Europe for research and to "get a feeling" for some of the places where Roads is set. She visited Belgium, Germany and Russia, but not Yalta. Still, her portrait of Yalta is vivid, "absorbed through things my parents and their parents talked about. Through them it became a very real place in my mind." She still hopes to visit someday.

Cramer says that since she was a child, she was always interested in writing. "I had written stories years ago, but they weren't good because I didn't know what I was doing," she says. It wasn't until later that she learned to "read critically like a writer," focusing on how the writing was done, the structure, what makes a certain passage so powerful, "how words are put together." Eventually the idea for Roads began to form, and "I knew it was more than a story. I realized it was a novel."

She continues to write and has several projects "in various stages of completion" that are "completely not ethnic." She calls this "a good exercise. Here are four people, and that's all you have to know." She also is shopping around a collection of short stories featuring Vera, "a character who entered my life and wouldn't leave."

The launch for Roads will take place at Watchung Booksellers on May 13. Cramer will also appear at bookstores and other sites in New York State, where she lives, and maybe at the Tolstoy Foundation, which for many years has helped immigrants from around the world settle here--including her own family when it was on the road to a new life in the U.S. --John Mutter

When Amazon begins collecting sales tax next month in New Mexico, Hawaii, Maine and Idaho, it marks the first time that the company will collect sales tax in all 45 states that have sales tax, which yesterday the American Booksellers Association called a victory for booksellers and Main Street retailers.

When Amazon begins collecting sales tax next month in New Mexico, Hawaii, Maine and Idaho, it marks the first time that the company will collect sales tax in all 45 states that have sales tax, which yesterday the American Booksellers Association called a victory for booksellers and Main Street retailers.

For

For  Roads, the story of a Russian family living in Yalta, in the Crimea, begins in the late 1930s, when life under Stalin has many challenges; some people go along with the regime while others continue to find sustenance in the old ways. Then the Nazis invade. As the occupation becomes increasingly difficult, the main characters--an older couple, their young daughter, and the daughter's husband--volunteer for agricultural work in Germany so that they can stay together--and be treated better than the many Russians who are being picked up in the streets and sent to Nazi labor camps. In Germany, they find they were lied to--but they survive appalling conditions and just miss being caught in the firebombing of Dresden in 1945. But as the war comes to its bloody conclusion, they're separated and, after the German surrender search for each other amid the chaos of postwar Germany--while needing to avoid the Red Army and allies who might return them to a grim fate in the Soviet Union. The characters are strongly drawn and fascinating, from the young dreamer Filip to his formidable mother-in-law, Ksenia, who cares for the family in a variety of ways--from finding and preparing food to providing the kind of grounding and clearsightedness needed to survive a string of harrowing situations.

Roads, the story of a Russian family living in Yalta, in the Crimea, begins in the late 1930s, when life under Stalin has many challenges; some people go along with the regime while others continue to find sustenance in the old ways. Then the Nazis invade. As the occupation becomes increasingly difficult, the main characters--an older couple, their young daughter, and the daughter's husband--volunteer for agricultural work in Germany so that they can stay together--and be treated better than the many Russians who are being picked up in the streets and sent to Nazi labor camps. In Germany, they find they were lied to--but they survive appalling conditions and just miss being caught in the firebombing of Dresden in 1945. But as the war comes to its bloody conclusion, they're separated and, after the German surrender search for each other amid the chaos of postwar Germany--while needing to avoid the Red Army and allies who might return them to a grim fate in the Soviet Union. The characters are strongly drawn and fascinating, from the young dreamer Filip to his formidable mother-in-law, Ksenia, who cares for the family in a variety of ways--from finding and preparing food to providing the kind of grounding and clearsightedness needed to survive a string of harrowing situations.

Congratulations to

Congratulations to  "My book smells better than your tablet."

"My book smells better than your tablet."  The Blue Hour

The Blue Hour What happens if you take a piece of Silicon Valley and drop it near Manhattan's Madison Square Park? In BuzzFeed culture writer Doree Shafrir's first novel, Startup, you get the same laid-back techie incubator open offices with nerf guns, iced coffee kegerators and lunchtime yoga classes--but you also get huddled sidewalk-smoking employees and four a.m. Uber rides to shotgun flats in Greenpoint. Hers is a funny, grittier New York version of kids in their 30s wearing fat do-not-disturb earphones while coding, Slacking, Tweeting and Instagramming to hustle a new app company from nowhere into that rarified billion-dollar unicornland.

What happens if you take a piece of Silicon Valley and drop it near Manhattan's Madison Square Park? In BuzzFeed culture writer Doree Shafrir's first novel, Startup, you get the same laid-back techie incubator open offices with nerf guns, iced coffee kegerators and lunchtime yoga classes--but you also get huddled sidewalk-smoking employees and four a.m. Uber rides to shotgun flats in Greenpoint. Hers is a funny, grittier New York version of kids in their 30s wearing fat do-not-disturb earphones while coding, Slacking, Tweeting and Instagramming to hustle a new app company from nowhere into that rarified billion-dollar unicornland.