|

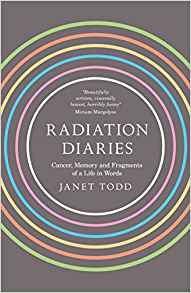

| Janet Todd |

Janet Todd is a British literary scholar known for her pioneering work on Aphra Behn, Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen and other women writers. For seven years, she was president of Lucy Cavendish College, Cambridge University. She has also published two novels, A Man of Genius and Lady Susan Plays the Game. While at Cambridge, she was diagnosed with three forms of cancer and underwent grueling treatment. She kept diaries of the experience in which she also reflected on her past, on literature, on feminism--all in frank, often comical and moving ways. Those diaries were published last month in book form as Radiation Diaries: Cancer, Memory and Fragments of a Life in Words (Fentum Press/dist. by Consortium, $14.95, 9781909572171). Here Todd reflects on what it was like to keep a diary and craft a book from it.

I'm a writer by inclination, profession and addiction. Having cancer for the third time and fearing (wrongly as it happens) I'd soon be dead, I set to writing myself out of fear.

In the early morning and late night, I recorded what happened in radiotherapy from my ignorant, fearful and bemused point of view. Comforting to think of this writing while prone under a nuclear machine deprived of written or spoken words.

Over the weeks, literary snippets welled up. I'd used books as crutch in a lonely but eager childhood, and then, in adult life, earned a living from "Literature." Stories and poems of childhood were now haunting me--along with the marvellous women, such as Aphra Behn, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Charlotte Smith, with whom I'd spent my grown-up time.

Another shadow was there too. In the 1950s, Jane Austen was rammed down the throat of school girls, even those like me who yearned for adventure tales and gothic horror. But now and for many decades she's meant more to me than any other novelist. Her feminism streams out in the most unexpected places: in the wonderful surreal stories she wrote as a child. The beautiful Cassandra with her trail of mischief is as sanguine and feminist a girl as you could want: cheery company in a tight place--like a hospital.

As for death and disease, there's something bracing about the way Jane Austen dispatches characters no longer wanted in her novel world: like Mrs Churchill in Emma or Dr Grant in Mansfield Park. A robust way to face the ultimate. Sort of "Exit. Pursued by a Bear" in fiction. And in her own life, going out--so far as writing's concerned--with mockery and humour. Hard to imagine the rollicking Sanditon as the last work of any other great realist writer.

Since I emigrated to America in 1968, feminism has dominated my academic and writing life. I was lucky to have met and worked with such exciting women as Adrienne Rich, Marilyn French and Elaine Showalter. American feminism did well by me: a joy to be embraced not in spite of being a woman but because of it. I could disinter and edit superb women then very little known, whose lives as well as works enthralled me.

Now in hospital, quite absurdly I felt angry with feminism. Had I really thought gender was a masquerade and the female body much the same as the male? Did I believe that the only basic hierarchy in life is gender? Had I been that crude? Maybe. Here, in this place, markers of femininity were a disconsolate fact, and power relations as intact as when I hid from prefects in the school cloakroom. There's something about undiluted power over a body that's just plain scary.

Now in hospital, quite absurdly I felt angry with feminism. Had I really thought gender was a masquerade and the female body much the same as the male? Did I believe that the only basic hierarchy in life is gender? Had I been that crude? Maybe. Here, in this place, markers of femininity were a disconsolate fact, and power relations as intact as when I hid from prefects in the school cloakroom. There's something about undiluted power over a body that's just plain scary.

I've been occasionally urged to write a memoir. Too chronological a form, I thought, too concerned with a verifiable past. Flattered, I resisted the idea and still do. But the urge to expose oneself is strong--or social media wouldn't flourish and Knausgaard be wealthy. By recording the childhood memories that surged into my mind during radiation weeks, I was giving into the urge.

My childhood is there for the writing, but is it for the reading? It occurred in three memorable places: Bermuda, Sri Lanka and a dreadful boarding school in Wales. The English upper-middle-class--of which I'm not a member--send their children to such schools, with some dire personal and national results. But, outside England, is this quaint custom of interest? Doubtful. As for a colonial past, has it simply become unspeakable?

However, within a diary written for myself and dominated by cancer, I could hint at my past--without analysing. After a lifetime of concentrating on the meaning, power and impotence of words, I felt blissfully free from any need to investigate as well as feel.

A duplex query. Without celebrity or sensational experience, why would anyone want to read about a life? Mothers in my time were prone to ask, "Who do you think you are?" No acceptable answer. To send out anything personal still feels like a plea, vanity, necessarily to be prefaced by "So and so urged me to publish this. I would not have done it otherwise. Not I."

But may not cancer justify revelation? I've let it do so. That raises another question: who except the ill (or courageous) would want to read about cancer?

There's the conundrum.

As for publishing, two things are relevant. My father's illness is prominent in the Diary--for, aged near 100, he landed in the same hospital at the same moment. A few months later he died--very much against his will. His was a seemly generation when it came to the body and inner self. I think he could not have welcomed my or his exposure. Or would he? He was an inveterate story-teller.

Second, I retired as the president of a Cambridge college with its demands for propriety and suitable dress.

Desire for some sort of self-expression burgeoned.

When a publisher kindly wanted to issue the Diary, I felt apprehensive and pleased. But what I'd written was in places too raw, too full of undigested web clutter. So, I crafted it. Surprisingly easy, for the work had become just a document to be edited.

I love editing. I love getting up early, making coffee and toast, then settling down in front of a mass of words that, like unmodeled clay, must be pressed and pummelled into shape. Crumbs stick in the keys.

No physical details were added or subtracted. Some of the quotations from largely unknown Welsh poetry and from Dylan Thomas--too many for anyone not weaned on him--were removed, more suitable ones inserted. I had a sort of gallows humour during treatment, seeing myself from outside as ridiculous and--yes--funny in my hospital gear and social bewilderment. I cut some of this. Yet I've always found humour the best and only way through some of life's most awful passages. Perhaps humour is too grand a word: what bubbles up in suffering is more like irrepressible schoolgirl giggling in church.

With a few nips and tucks, I wanted to make myself a character in my own eyes and, when published, in the eyes of any reader. Having finished, I hope this character may help to stir a response of "Me too." I also hope the Diary is entertaining.

So now, back to writing. As Jane Austen remarked, it is as well to have as many holds on happiness as possible. Writing is the first of mine.

"In Frankfurt, I began to understand that the role the bookstore plays in each of our communities is the same around the world. This universality was validated as I visited bookstores in other cities during my trip. In Paris, Frankfurt, and Berlin, shops of different sizes, specialties, and styles reflected their environment, and all were busy. In Paris, Shakespeare and Company even had a velvet rope to regulate the line of people waiting for admittance.

"In Frankfurt, I began to understand that the role the bookstore plays in each of our communities is the same around the world. This universality was validated as I visited bookstores in other cities during my trip. In Paris, Frankfurt, and Berlin, shops of different sizes, specialties, and styles reflected their environment, and all were busy. In Paris, Shakespeare and Company even had a velvet rope to regulate the line of people waiting for admittance.

IPC.0204.S3.INDIEPRESSMONTHCONTEST.gif)

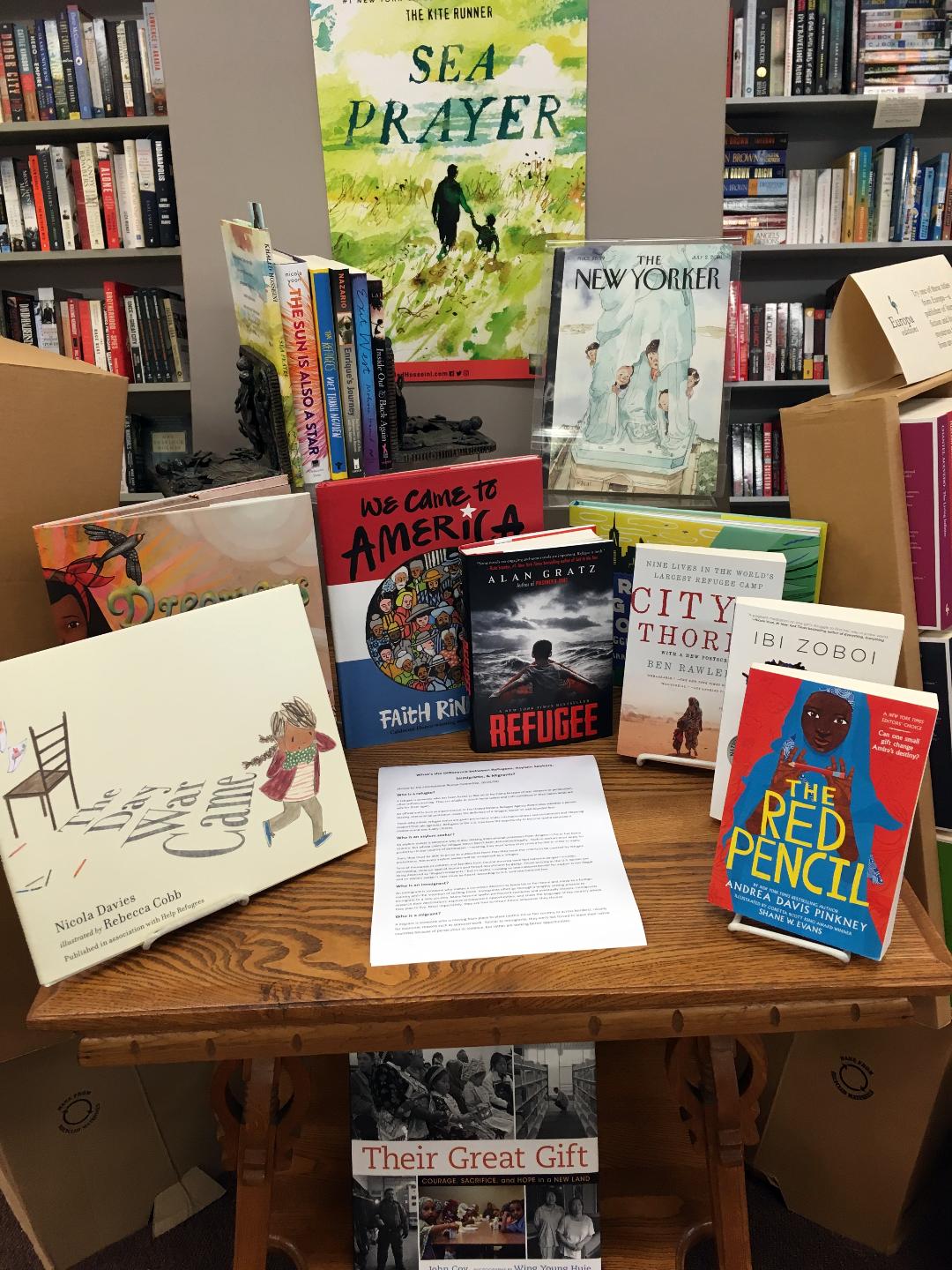

Aardvark Books

Aardvark BooksIPC.0211.T4.INDIEPRESSMONTH.gif)

Porter Square Books

Porter Square Books Sourcebooks is implementing an Indie Rapid Replenishment program for the 2018 holiday season. Starting November 5 and continuing through December 19, orders for in-stock Sourcebooks titles received from independent bookstores by 11 a.m. CST Monday through Friday will ship no later than the following business day, weather and transport conditions permitting, for arrival at booksellers' doors within two days. Orders received after the cutoff on Friday and over the weekend will be shipped on Monday, the company said, adding that its program will give all independent retailers in the U.S. the benefit of ship times of two days or less.

Sourcebooks is implementing an Indie Rapid Replenishment program for the 2018 holiday season. Starting November 5 and continuing through December 19, orders for in-stock Sourcebooks titles received from independent bookstores by 11 a.m. CST Monday through Friday will ship no later than the following business day, weather and transport conditions permitting, for arrival at booksellers' doors within two days. Orders received after the cutoff on Friday and over the weekend will be shipped on Monday, the company said, adding that its program will give all independent retailers in the U.S. the benefit of ship times of two days or less.

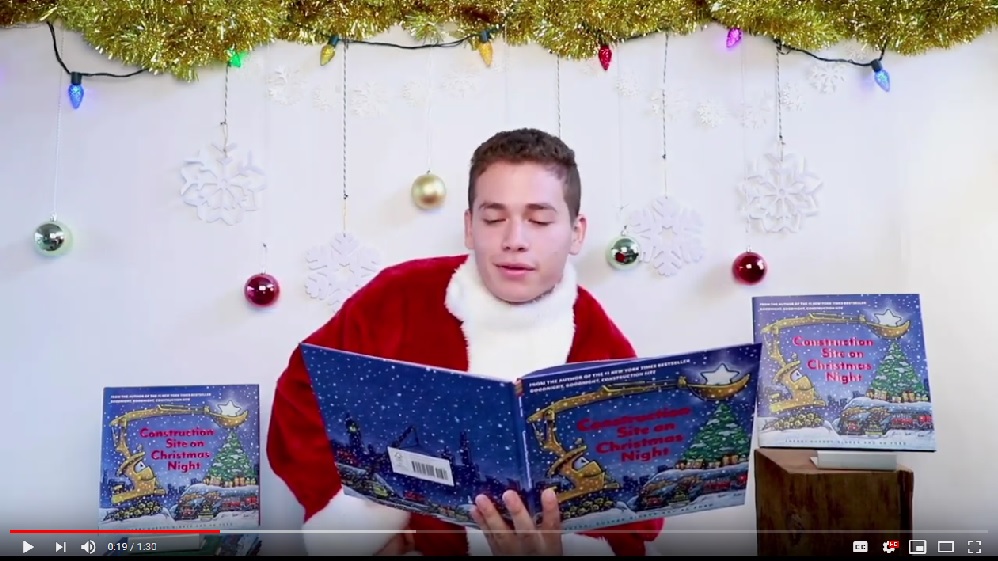

Northwind Book & Fiber

Northwind Book & Fiber Earlier this week, we featured "a

Earlier this week, we featured "a  Construction Site on Christmas Night

Construction Site on Christmas Night The

The

Now in hospital, quite absurdly I felt angry with feminism. Had I really thought gender was a masquerade and the female body much the same as the male? Did I believe that the only basic hierarchy in life is gender? Had I been that crude? Maybe. Here, in this place, markers of femininity were a disconsolate fact, and power relations as intact as when I hid from prefects in the school cloakroom. There's something about undiluted power over a body that's just plain scary.

Now in hospital, quite absurdly I felt angry with feminism. Had I really thought gender was a masquerade and the female body much the same as the male? Did I believe that the only basic hierarchy in life is gender? Had I been that crude? Maybe. Here, in this place, markers of femininity were a disconsolate fact, and power relations as intact as when I hid from prefects in the school cloakroom. There's something about undiluted power over a body that's just plain scary. A self-described "Luddite," Helen Schulman last explored the insidious effects of modern technology in her 2011 novel, This Beautiful Life. Now, in Come with Me, she goes from exploration to speculation with a story inspired by the tech wunderkinds and venture capitalists of Silicon Valley, whose billion-dollar attempts to "hack" biology and cheat death are modern answers to an ancient dilemma.

A self-described "Luddite," Helen Schulman last explored the insidious effects of modern technology in her 2011 novel, This Beautiful Life. Now, in Come with Me, she goes from exploration to speculation with a story inspired by the tech wunderkinds and venture capitalists of Silicon Valley, whose billion-dollar attempts to "hack" biology and cheat death are modern answers to an ancient dilemma.

Four years ago, I wrote that if you don't work in the book trade, it's hard to explain what happens at an event like the

Four years ago, I wrote that if you don't work in the book trade, it's hard to explain what happens at an event like the

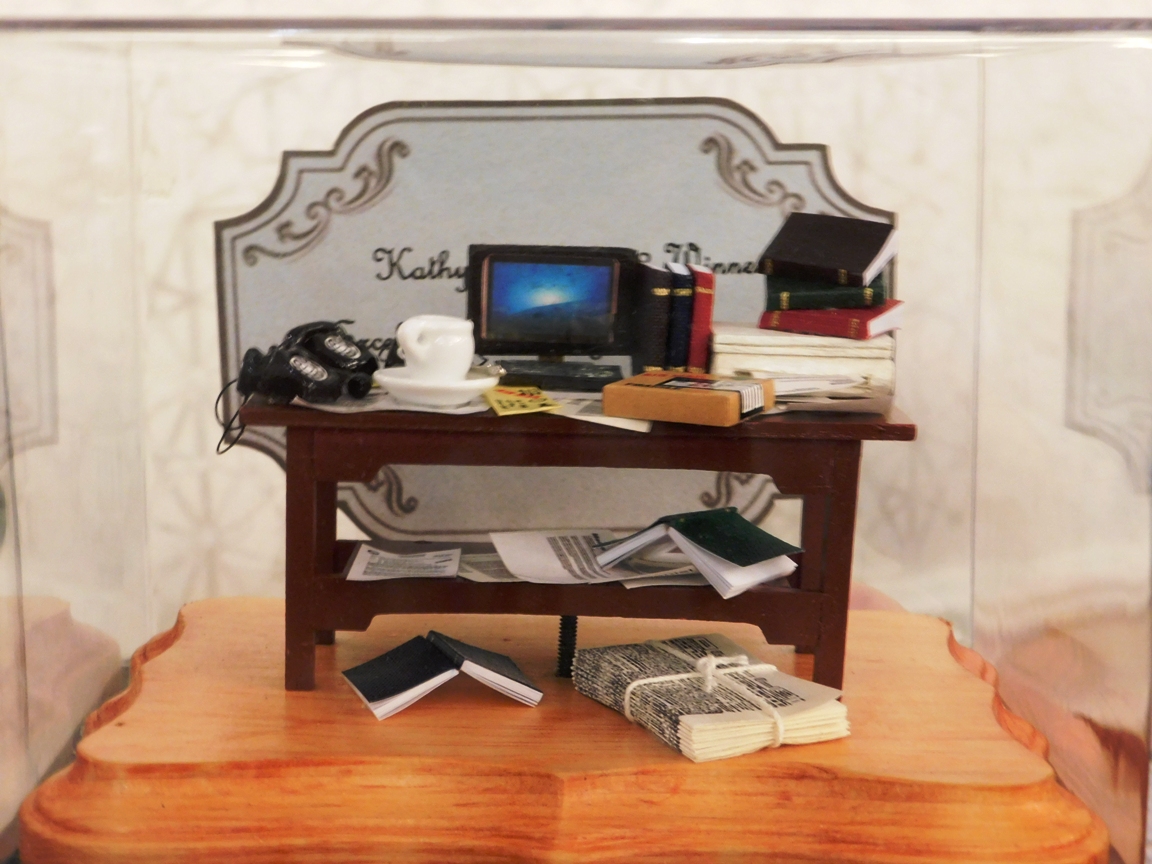

Boss then presented her with a handmade "Excellence in Ability to Respond to Multiple Stimuli" trophy, featuring a little desk, upon on which are scattered telephones, a computer, a fax machine, books, newspapers, packages, memos and a cup of coffee. "So, with love and respect, this is for Kathy," he added.

Boss then presented her with a handmade "Excellence in Ability to Respond to Multiple Stimuli" trophy, featuring a little desk, upon on which are scattered telephones, a computer, a fax machine, books, newspapers, packages, memos and a cup of coffee. "So, with love and respect, this is for Kathy," he added.