With a significant number of independent bookstores forced to move or close locations due to high rents and occupancy costs, Shelf Awareness reached out to booksellers across the country to hear their stories about rising rents, lease negotiations and landlords, and to ask what advice they'd share with other indies in similar situations.

Although the American Booksellers Association's ABACUS results show that occupancy costs for indie bookstores have not risen sharply over the last four years when averaged across the nation, the reality in certain parts of the country can be stark. And while no two rental agreements are exactly alike, some common trends emerged when talking with booksellers in the Bay Area, New York City, Southern California and beyond. In particular, booksellers emphasized the need to educate landlords about the financial realities of the book business and to follow a diverse business model.

Each installment of the series will focus on a single bookseller. More will follow over the next several days.

|

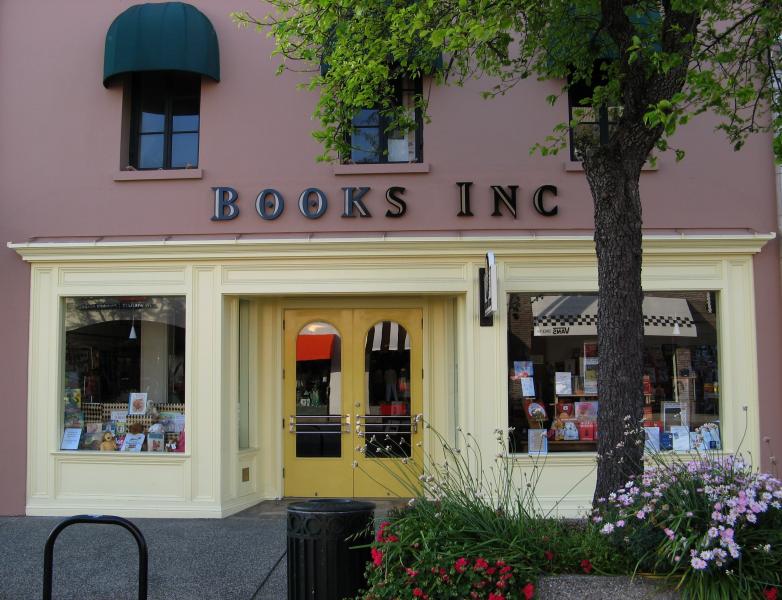

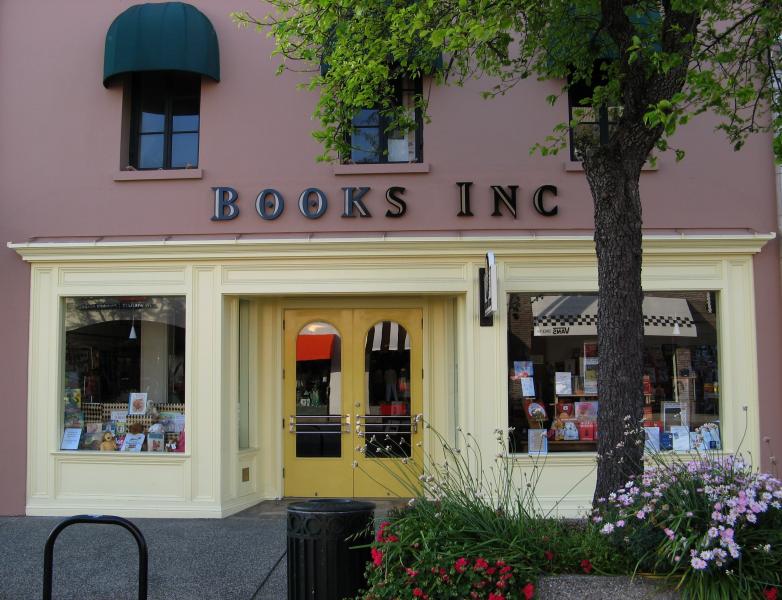

| Books Inc. in Burlingame |

In October 2018, Books Inc. president and chief executive Michael Tucker announced that the store's Burlingame, Calif., location, which has been in business since August 2000, would close in early 2019. The reason was strikingly familiar to booksellers in some parts of the country: commercial rents in Burlingame, which is just south of San Francisco, have risen tremendously in the past five to ten years and in particular, the stretch of Burlingame Avenue on which Books Inc. is located has become too expensive for anything but the largest national chains.

In recent years, Tucker and his Burlingame landlord had had candid conversations about how the latter was not seeing revenue commensurate with what he needed and Tucker could simply not afford rents that high. When the Burlingame lease came up in 2017, Tucker secured one more year at a reduced rent while the owners searched for a new tenant.

In the sequence of events, there was one change that points to a strong bargaining point in similar situations: in the months since they announced the closure, Tucker and the Burlingame staff have seen their customers "up in arms." Tucker explained: "Five or six years ago, with the decline in bookstores we were seeing, people thought we were a dead commodity. Now people recognize our value to the community. And that if they lose [a bookstore], they might never get one back."

Including the Burlingame store, Books Inc. has 11 locations in the Bay Area, all of them in leased storefronts. Most of the leases are for five years with an additional five-year option. Given the number of stores Books Inc. has, it feels that a rent negotiation is "always coming up," Tucker said, adding: "If we didn't have landlords that were willing to bring us in undermarket, we couldn't exist out here to begin with. We've got some of the most expensive real estate in the country."

The case of another Books Inc. location, in San Francisco's Laurel Village, shows the power of community support. That branch has been in business since 1976, and for decades had the same landlord in Salt Lake City, Utah. When that original landlord passed away around seven years ago, his sons took over, and Tucker recalled that they were "gung-ho" on "hitting the ground running" and raising the store's rent. Through a huge showing of community support, which included letters from schools, local librarians, their District Supervisor and some "heavy hitter" customers like Senator Dianne Feinstein and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Books Inc. was able to convince the new landlords of the store's value to the community.

For that store's next five-year lease, Tucker continued, the landlords did not raise the rent, and for the subsequent 10-year lease, they "actually lowered the rent in recognition of the mandated $15 per hour minimum wage increase." In 2017, the Laurel Village store also received Legacy Business status, which grants a significant rent rebate from the city as an incentive for the landlord to give them a long-term lease.

In dealing with landlords, Tucker recommended that booksellers be in touch with their landlords frequently, even if a negotiation isn't on the horizon, and hopefully have lunch or dinner with them at least a couple of times per year. The goal, he said, is to let them "see and participate in what you're doing," and "become enmeshed in what's going on." That way, when a lease does finally come up, it's not just about a legal arrangement.

Tucker suggested being as transparent as possible when going into negotiations. While booksellers shouldn't "plead poverty," they should explain the nature of the business and the slim margins with which they work. At the same time, booksellers can try to sell landlords on the less tangible benefits that indies provide as anchor tenants and community hubs. Tucker also frequently makes use of a Microsoft Excel formula that can clearly illustrate a store's finances and show the point at which a given rent cost would become untenable. If a landlord or prospective landlord won't budge past a certain number, Tucker said, then it's simply a non-starter. But if a landlord really gets it, they can find ways to make it work.

"Communities by and large want a bookstore now," Tucker said. "Show [landlords] this is what we can do here, but here's what we need." --Alex Mutter

IPC.0218.S4.INDIEPRESSMONTHTITLES.gif)

IPC.0211.T4.INDIEPRESSMONTH.gif)

Trenessa Williams, founder of the online bookshop

Trenessa Williams, founder of the online bookshop

Last Friday, Wilco front man Jeff Tweedy visited booksellers in Los Angeles to sign stock of his recent memoir Let's Go (So We Can Get Back) (Dutton). Pictured: Sara Stringer, manager at

Last Friday, Wilco front man Jeff Tweedy visited booksellers in Los Angeles to sign stock of his recent memoir Let's Go (So We Can Get Back) (Dutton). Pictured: Sara Stringer, manager at  An Anonymous Girl

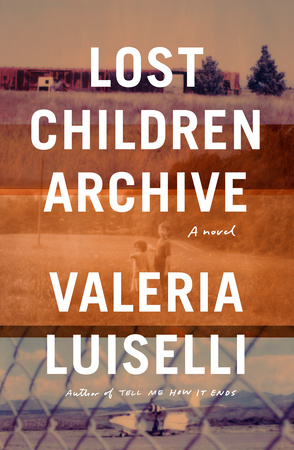

An Anonymous Girl In her spellbinding novel Lost Children Archive,

In her spellbinding novel Lost Children Archive,