|

| photo: Hannah Knowles |

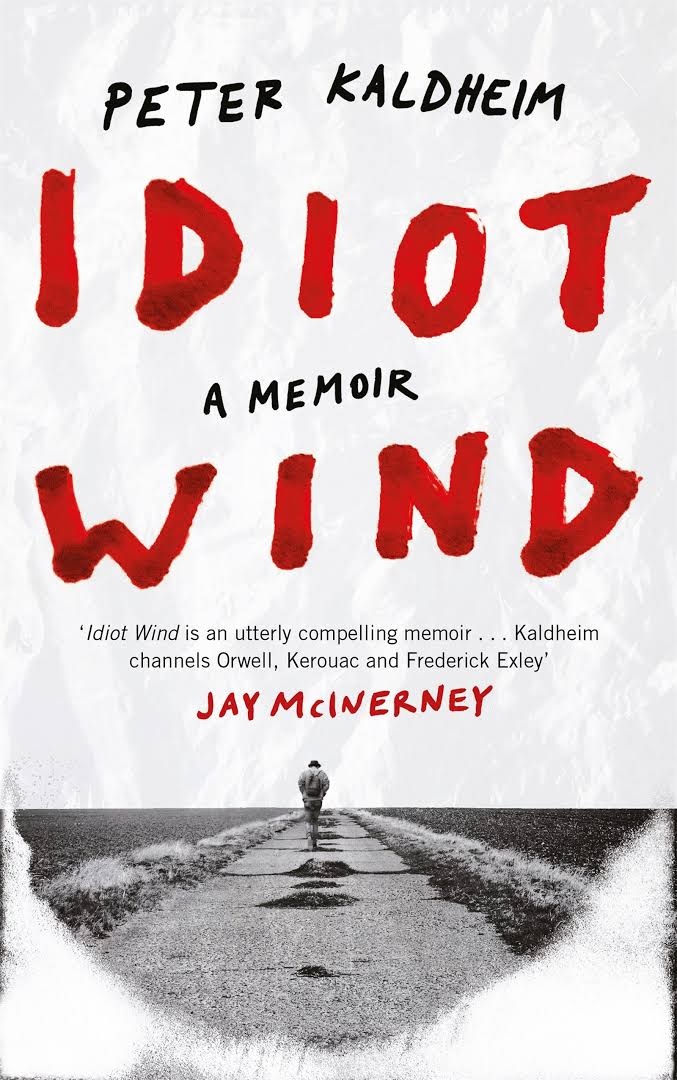

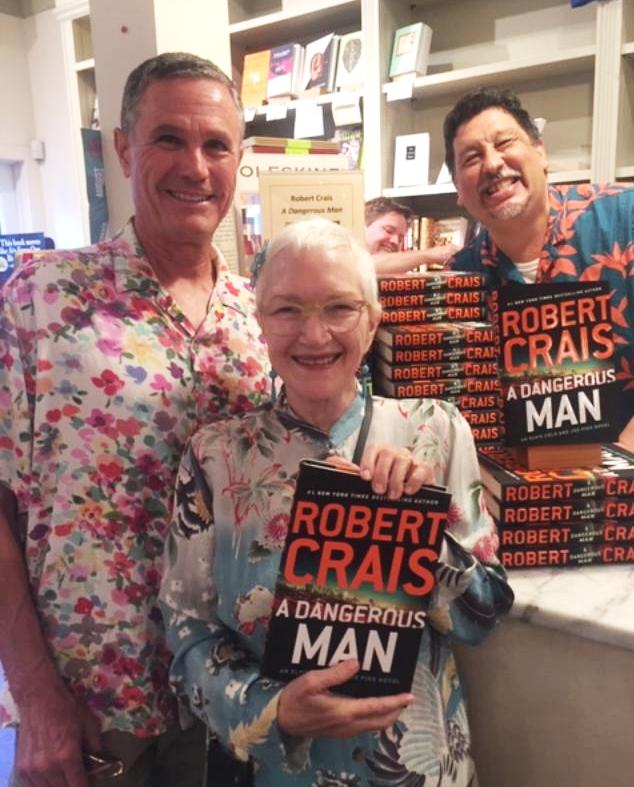

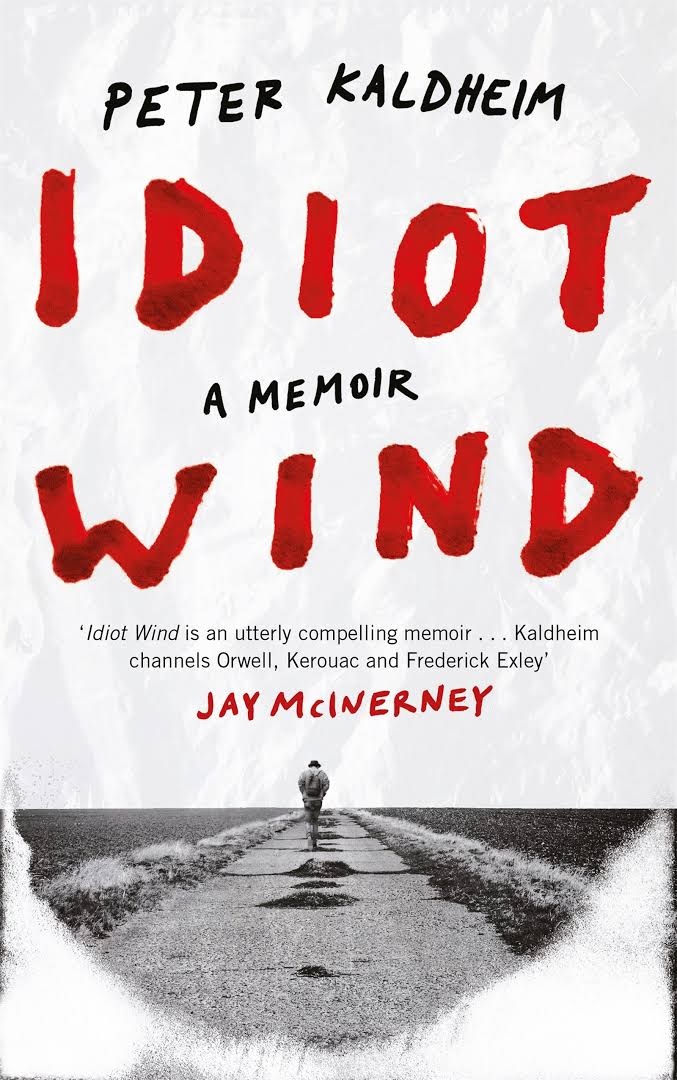

Peter Kaldheim, a native of Brooklyn, N.Y., studied English and Classics at Dartmouth College. He worked as an editor and freelance writer in Manhattan until an addiction to drugs landed him in jail. His first book, the memoir Idiot Wind, was just published by Canongate, and will be issued in Spanish, French, Italian and Dutch in 2020. Kaldheim now lives in Lindenhurst, N.Y.

On your nightstand now:

Sam Lipsyte's comic masterpiece, Hark!, the funniest American novel I've read since Stanley Elkin's The Dick Gibson Show (1971). Vacuum in the Dark by Jen Beagin, which continues the story of Mona, the quirky cleaning lady I fell in love with when she first appeared in Pretend I'm Dead (how can you not love a character who skewers her alcoholic father with remarks like, "His mouth was a coffin she'd spent years wanting to nail shut"?). Memories of the Future, the latest novel from Siri Hustvedt, who continues to challenge her readers with brain-teasing observations (e.g., "I have always believed that memory and imagination are a single faculty"). And, finally, two brief gems which prove that stream-of-consciousness is still a vibrant fictional strategy: Solar Bones by the Irish novelist Mike McCormack and Little Boy by the recent centenarian Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Ah, that brings back fond memories! By far, my favorite book would have to be And to Think that I Saw It on Mulberry Street by Dr. Seuss.

Your top five authors:

Now there's a migraine-inducing question if I ever saw one! The only way I can answer it is by narrowing my focus to American novelists of the postwar generations (with apologies to James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Jorge Luis Borges, et al.). That said, my "starting five" would include Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo, Robert Stone, Denis Johnson and Dana Spiotta--all of them masterful stylists whose novels go deep in their exploration of the various manias and self-delusions that lurk beneath the surface of the American experiment.

Book you've faked reading:

I can't recall ever faking when it comes to books--if only I could say the same about other areas of my life! However, occasionally I've encountered a book I just couldn't bring myself to finish, and Finnegans Wake is probably the prime example. Much as I admire James Joyce, his final novel has stumped me for decades, and I fully expect to go to my grave without ever getting past page 67.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Ever since I first came across Karolina Waclawiak's debut novel, I have been urging others to read How to Get into the Twin Palms, the story of a lonely young Polish woman who longs to "pass" as a Russian immigrant so she can gain admittance to the Twin Palms, a private club run by Russian mafiosi located across the street from her Los Angeles apartment. It's an ambition she knows would scandalize her Polish mother, who believes that Russians "are crooks and beneath us." Of course, the Russians feel the same way about the Poles, and as Waclawiak trenchantly observes, "It had always been a question of who was under whom." Waclawiak's slim novel is rich in such home truths and marks her as a writer America can be justly proud to claim as one of our own.

Book you've bought for the cover:

I can still vividly recall the afternoon in 1972 when I stumbled upon Gilbert Sorrentino's second novel, Steelwork, in the back room of the venerable Gotham Book Mart in Manhattan's Diamond District. The dust jacket featured a photograph of a street sign from the corner of Fourth Avenue and 68th Street in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, the working-class neighborhood where my parents grew up (as Sorrentino's contemporaries) and where I was born. So, of course, I had to buy the book, and it proved to be a revelation--a homegrown work of startling genius, full of neighborhood characters that are as memorably rendered as the Irish locals in James Joyce's Dubliners.

Book you hid from your parents:

The only book I ever felt the need to keep hidden from my parents was a City Lights collection of Charles Bukowski stories called, Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions, and General Tales of Ordinary Madness.

Book that changed your life:

In a very real sense, Jack Kerouac's On the Road didn't just change my life, it saved my life. When I first read On the Road in the summer of 1965, I was a 16-year-old wannabe writer with an unhelpful crush on the clipped prose style of Ernest Hemingway, but Kerouac's style, with its jazz-inspired rhythms and mad, onrushing energy, opened my eyes to a whole new way of writing and immediately put "Papa" Hemingway in my rearview mirror. Twenty-two years later, after a decade-long slide into alcohol and cocaine addiction had left me homeless on the streets of Manhattan, I would flee New York and hit the road like Jack Kerouac, hitchhiking and panhandling my way across the country in a last-ditch bid to find a place out west where I could begin to rebuild my life. It was a humbling journey, with no lack of hardships, but I kept my spirits up by jotting down daily notes about the people and places I encountered as I drifted toward the Pacific, hoping that one day those notes would provide the raw material for my own version of Kerouac's road book--a pipe dream, perhaps, but it allowed me to get through each day with a scrap of dignity intact, and in the end those road notes would become the basis for Idiot Wind. So, thank you, Jack!

Favorite line from a book:

Like every fan of Thomas Pynchon, I remain in awe of the opening line of Gravity's Rainbow ("A screaming comes across the sky."), but there's a line in Henning Mankell's novel Italian Shoes that I'm even more fond of: "It's just as easy to lose your way inside yourself as it is to get lost in the woods or in a city."

Five books you'll never part with:

On the Road by Jack Kerouac, The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon, Libra by Don DeLillo, A Fan's Notes by Frederick Exley, Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone. All five are books that continue to offer up fresh pleasures each time I reread them.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

My vote would go to A Fan's Notes, Frederick Exley's "fictionalized memoir," which my friend Gerald Howard, an editor at Doubleday, refers to as "the foundational text in Male Failure Studies." When I first read A Fan's Notes in 1970, I was blown away by its harrowing but hysterically funny portrait of an alcoholic writer facing up to the fact that he'd been fated to watch from the sidelines while others--like his college classmate (and star football player) Frank Gifford--cashed in on the American Dream. Exley's gift for turning the disasters of his life into stories that are simultaneously sad and side-splittingly funny is unrivaled. Reading A Fan's Notes for the first time, I felt like I was making the Stations of the Cross high on laughing gas, and I'd happily jump into Mr. Peabody's "Wayback Machine" for the chance to revisit that week of my life again.

Three down-and-out memoirs that most resemble Idiot Wind:

George Orwell's classic Down and Out in Paris and London, which set the standard for all future examinations of poverty and homelessness, would have to top the list, with John Healy's The Grass Arena and Nick Flynn's Another Bullshit Night in Suck City coming in a close second and third.

Last night, an SRO crowd at

Last night, an SRO crowd at

"Have you seen our

"Have you seen our  "Endless book summer,"

"Endless book summer,"  New Kings of the World: Dispatches from Bollywood, Dizi, and K-Pop

New Kings of the World: Dispatches from Bollywood, Dizi, and K-Pop

Book you're an evangelist for:

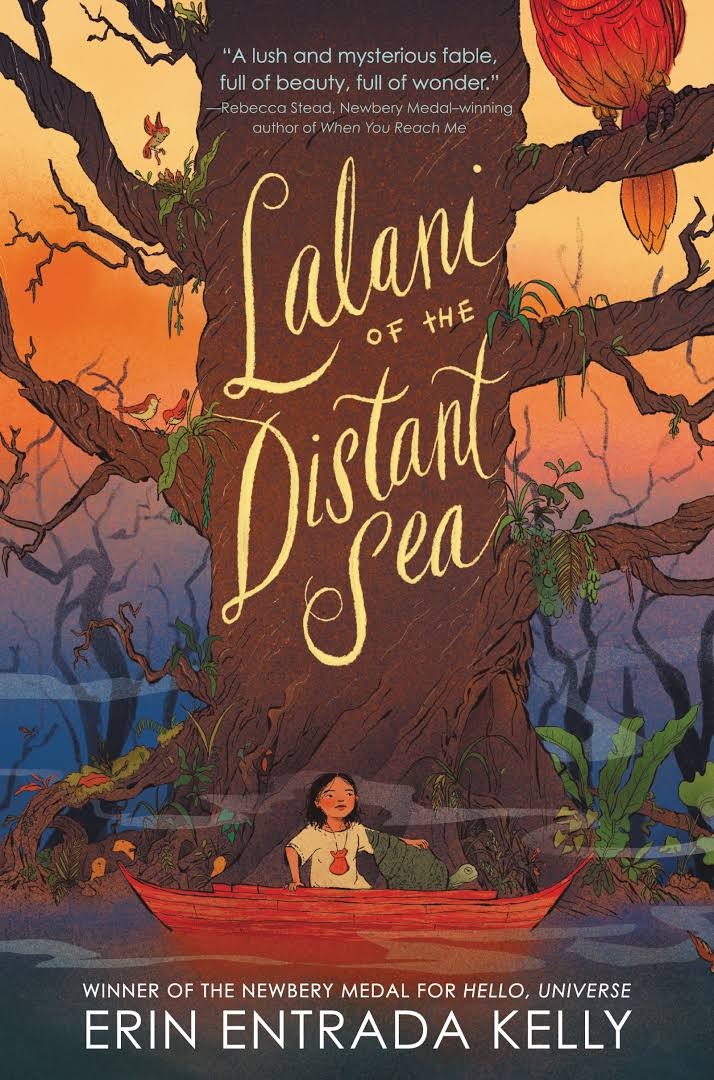

Book you're an evangelist for: Newbery Medal winner Erin Entrada Kelly (

Newbery Medal winner Erin Entrada Kelly (