Helene Goldfarb, president of the Feminist Press board, met press founder Florence Howe in 1947, when she was a freshman at Hunter College and Howe was a sophomore. Sadly, Howe died in September at the age of 91. Here Goldfarb reflects on the mission of inclusion behind the establishment of the nonprofit publishing company, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. All are welcome to join a birthday party in the form of a virtual panel and fundraiser next Wednesday, November 18, at 7 p.m. Eastern.

Helene Goldfarb, president of the Feminist Press board, met press founder Florence Howe in 1947, when she was a freshman at Hunter College and Howe was a sophomore. Sadly, Howe died in September at the age of 91. Here Goldfarb reflects on the mission of inclusion behind the establishment of the nonprofit publishing company, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. All are welcome to join a birthday party in the form of a virtual panel and fundraiser next Wednesday, November 18, at 7 p.m. Eastern.

Before Florence Howe founded the Feminist Press, she was teaching English literature at Goucher, a women's college in Maryland. She had spent a large part of her vacation time in the late 1960s teaching at freedom schools in the South, which opened her eyes to equality of all kinds.

One day Florence was speaking of all the writers of importance when her students asked her, "Where are the women writers?" and it made her stop and think. If there were women writers in the curriculum, they were few and far between--Louisa May Alcott and the Brontë sisters were the only ones who came quickly to mind. She thought this lack of women's literature was an issue that publishing houses would be interested in helping rectify. She went to three, but while the editors were interested, the financial men said that books by women would not sell. No market, no publishing.

|

| Florence Howe |

At the time the Press was started, there was no "board of directors," but rather a group of interested people who had gotten together in Florence Howe and Paul Lauter's apartment to see what they could do. Elaine Hedges was also one of the three pioneers who worked on this. Because feminism includes people of all genders in its meaning, and because they wanted the Press to be inclusive in its work for equity, the Feminist Press was the logistical name. The Women's Press would have excluded men, and did not fill the needs of the group.

I think that growing up in the '40s and '50s, going to an all-women's college, and being a science major where many of my professors were women, made me slightly oblivious to the needs that Florence saw as she learned about the lack of women writers. Working with her and the Press has opened my eyes. It has made it possible for me to read a wider variety of books (and I try to read all the books we publish). I really enjoy our books and understand even more about how a lack of equality narrows perspectives.

Like our founder, Florence, the Feminist Press never stops searching to make things better. As for the rest of the board, we have all reached the same conclusion that without diversity (including diversity of gender, race, dis/ability, sexuality, age and beyond), there can be no equality. We have operated on this principle from the beginning and continue to strengthen this commitment. Fifty years strong, we publish books that ignite movements and social transformation. Celebrating our legacy, we lift up insurgent and marginalized voices from around the world to build a more just future.

By the time I started working with the Press, we had left Baltimore and moved to SUNY Old Westbury. The Press was small, and all members of the staff did everything, including packing and mailing the books to bookstores around the country. When something was needed, we rushed to fill the space. When we filled the need and others took on publishing the works we had exposed them to, we found a new need. By the mid 1980s, other publishers had also realized the financial and literary value of reprinting books written by women. When that field became more competitive, we focused on finding overlooked "gems" like The Yellow Wallpaper, and expanded our reach to international writing and literature in translation as well.

Sometimes board members were not as happy with the staff and Florence about what we chose to publish, and that could and did cause problems. Despite this, we worked them out and found ways to please as many of us as possible. Almost no one on the board of directors, for example, initially approved of our Women Writing in India collection when Florence first proposed it in the 1980s because of its international focus and the difficulty of securing funding. Today, however, I think all of us would agree that collections like this one have made the Feminist Press a leader in international feminist fiction and writing in translation. I think one of the biggest challenges as a nonprofit press has been getting some corporations and other funders to understand what feminism means. In the past, many corporate funders said that if we changed our name they might be more interested. Due to shifts in culture, this has gotten better over the years. But it is not gone. The lack of understanding of what feminism is and means is a mystery to me.

Being at the Feminist Press was not without its challenges, which came to a head one day when the staff arrived at their office, a lovely house on the Old Westbury campus and a Quonset hut that we used to store and package the books, only to find that it had been set on fire during the night. Much of our work was destroyed. The fire department experts confirmed to us that the fire was a clear case of arson, although they advised us to say instead that it had been caused by "an electrical failure in the kitchen." The arsonist was never found. The only "good" thing, if there is a good thing, was that this was done in the early morning hours when no one was there. It was at that time that Florence began looking for other quarters where she and the staff would be safe. Within a few years, we moved to CUNY.

Having women writers in the curriculum, and including our books and other nonprofit publishers' books in the curriculum, has made education more inclusive. Having Feminist Press books used not only in literature courses but in women's studies courses (which did not exist until the 1970s), history courses and wherever else they fit has been a big change. We have published feminist books focused on art, music, disabilities and other areas where our works are needed. Throughout our history, we would find a niche, fill it, and when the mainstream presses picked up on it, we would move on to another area to develop. This has helped us remain a press of discovery. We define what is missing and help it become more mainstream. We have become the vanguard for books on contemporary feminist issues of equality and gender identity, with authors as various as Anita Hill, Justin Vivian Bond, Juli Delgado Lopera, Brittney Cooper, Michelle Tea, Cristina Rivera Garza, and Ann Jones, among many others.

Harvard Book Store, Cambridge, Mass., temporarily closed yesterday after learning that one staff member tested positive for Covid-19 on Tuesday. That person last worked in the store space on Sunday, November 8, and is "feeling mostly well, and we are hopeful for a speedy recovery," the store announced online and in messages to customers.

Harvard Book Store, Cambridge, Mass., temporarily closed yesterday after learning that one staff member tested positive for Covid-19 on Tuesday. That person last worked in the store space on Sunday, November 8, and is "feeling mostly well, and we are hopeful for a speedy recovery," the store announced online and in messages to customers.

It's not a surprise, but it's official: the American Booksellers Association's Winter Institute 16

It's not a surprise, but it's official: the American Booksellers Association's Winter Institute 16

The

The

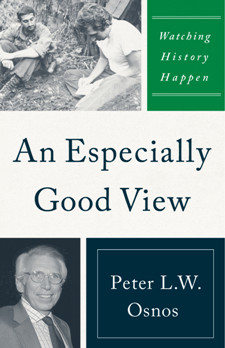

Peter Osnos, founder of PublicAffairs, an editor and publisher at Random House and longtime correspondent and editor at the Washington Post, has co-founded a publishing house that will release his memoir, An Especially Good View: Watching History Happen, in May.

Peter Osnos, founder of PublicAffairs, an editor and publisher at Random House and longtime correspondent and editor at the Washington Post, has co-founded a publishing house that will release his memoir, An Especially Good View: Watching History Happen, in May. Platform Books describes An Especially Good View as a reported memoir that spans Osnos's half century in journalism and publishing, offering personal insights and reflections on a life that began during World War II in India, where he was born. As a journalist, Osnos worked for the legendary I.F. Stone and was a correspondent for the Washington Post covering the war in Vietnam and the Soviet Union in the Cold War era. He was also the Post's foreign and national editor. He then spent 12 years at Random House as an editor and publisher before founding PublicAffairs in 1997.

Platform Books describes An Especially Good View as a reported memoir that spans Osnos's half century in journalism and publishing, offering personal insights and reflections on a life that began during World War II in India, where he was born. As a journalist, Osnos worked for the legendary I.F. Stone and was a correspondent for the Washington Post covering the war in Vietnam and the Soviet Union in the Cold War era. He was also the Post's foreign and national editor. He then spent 12 years at Random House as an editor and publisher before founding PublicAffairs in 1997. In Durango, Colo.,

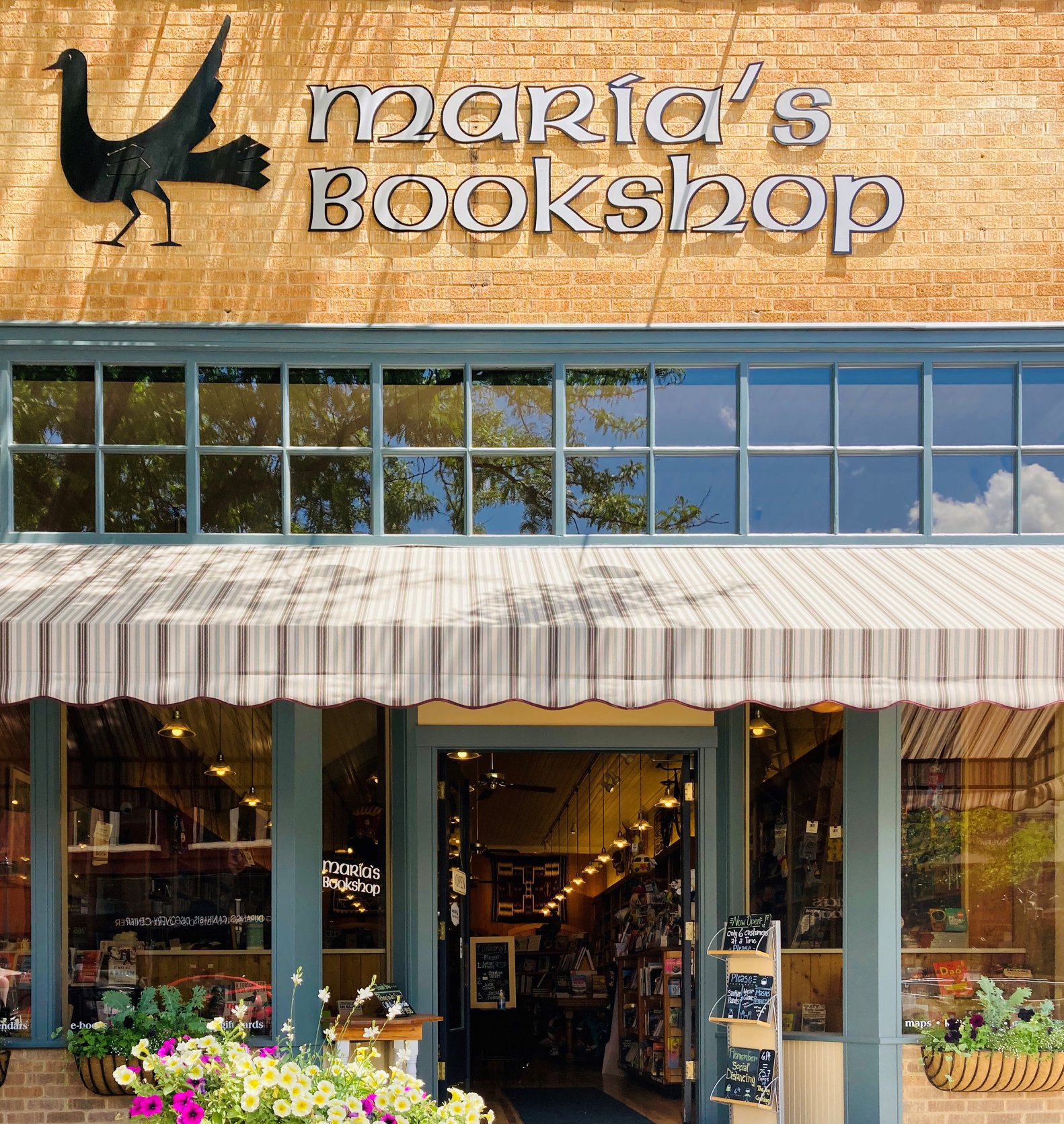

In Durango, Colo.,  On the subject of the holidays, Schertz said they are anticipating very low sales numbers this year compared to prior years. In most years, he explained, the store's holiday sales are "largely dependent on packing the store to a nearly uncomfortable level from Thanksgiving through Christmas." That's obviously impossible in 2020, so numbers are expected to be low and the store's buying has reflected that. That said, Schertz and his team would love to be pleasantly surprised.

On the subject of the holidays, Schertz said they are anticipating very low sales numbers this year compared to prior years. In most years, he explained, the store's holiday sales are "largely dependent on packing the store to a nearly uncomfortable level from Thanksgiving through Christmas." That's obviously impossible in 2020, so numbers are expected to be low and the store's buying has reflected that. That said, Schertz and his team would love to be pleasantly surprised.

Winter is coming to

Winter is coming to

Moonflower Murders

Moonflower Murders Helene Goldfarb, president of the Feminist Press board, met press founder Florence Howe in 1947, when she was a freshman at Hunter College and Howe was a sophomore. Sadly,

Helene Goldfarb, president of the Feminist Press board, met press founder Florence Howe in 1947, when she was a freshman at Hunter College and Howe was a sophomore. Sadly,

Editor and author extraordinaire

Editor and author extraordinaire