|

| photo: Pia Elizondo |

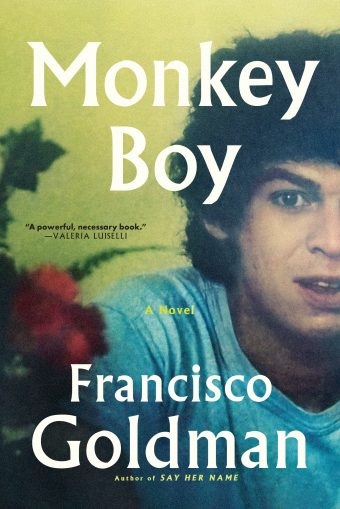

Francisco Goldman is the author of Monkey Boy (Grove, May 4, 2021), in which he traces a life, not unlike his own, over a five-day journey from New York to Boston. He lives in Mexico City with his wife and their daughter, who just turned three. Monkey Boy is Goldman's first novel since Say Her Name (winner of 2011 Prix Femina Étranger), which was followed by the memoir The Interior Circuit (2017 Blue Metropolis Premio Azul). In 2020, a documentary based on his nonfiction book The Art of Political Murder aired on HBO. Goldman has written regularly for the New Yorker.

On your nightstand now:

Sharing my nightstand with One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish, Goodnight Moon and Madeline are Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (rereading for first time since around college, wrenching and thrilling); two novels by good friends: Poeta Chileno, acclaimed as an instant classic by Spanish-language critics, which is by my next-door neighbor Alejandro Zambra, and Radius, by the astonishing Rebecca Brian; and The Passion According to G.H., by Clarice Lispector, Idra Novey's translation.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Oh my, so many; of course, there were stages, that warm yellow shade of happiness I still associate with Babar and Curious George. I still vividly remember, in first grade, Miss Hogarth reading out loud from Charlotte's Web and ecstatically floating up out of my seat and over my classmates' heads to the front row to be closer to her and to the book in her hands, the first time I'd ever had such a reaction to literature. By fourth grade I was big into Landmark History books and especially books about football, of which Pro Quarterback by the great Y.A. Tittle, co-written with Howard Liss, was my favorite by far. This book, as any reader of Monkey Boy will get, really hit home. When I was 12, Aunt Lee gave me The Hobbit, and I fell in love, and soon after ran away to join the Fellowship of the Ring.

Your top five authors:

Chekhov, Tolstoy, Natalia Ginzburg, Toni Morrison, Roberto Bolaño. At different times in my life that list has been comprised of different writers, but Tolstoy and Chekhov are constants.

Book you've faked reading:

This is incredibly embarrassing for any writer with Guatemalan roots to admit, but I've never read El Señor Presidente, the most famous novel by our 1967 Nobel Prize for Lit winner, Miguel Ángel Asturias. I've tried a few times, in English and Spanish, yet always abandoned it, I don't even know why, I didn't dislike it. There's a new commemorative edition out, and I'm going to read it soon, I promise.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Isaac Babel's Red Cavalry Stories. A fervent young Bolshevik and Jew, Isaac Babel rode as a war correspondent with the Red Cavalry into Poland. What he witnessed was barbarous cruelty, cynicism, violence, much as if directed against Polish Jewish peasants. Six years later he published these beautiful and terse short stories that devastate, shock, break your heart. It made Babel famous and, 15 years later, Stalin had him killed. In its old pale-green Penguin edition, this book was my companion for years. Now you can read it in The Complete Works

Book you've bought for the cover:

Book you've bought for the cover:

Little Green Donkey by Anuska Allepuz, who also did the charming cover and illustrations. We're really into burros in our house. I saw it displayed in a children's store in NYC when I flew up for my vaccine shot, and bought it on sight.

Book you hid from your parents:

The Landmark Books edition of The Rise and Fall of Adolf Hitler, an abridged version for young readers of the William Shirer tome. The first time I brought it back from our Massachusetts town's library, my mother returned it; I checked it out again, hid it in my room, and my darling Mamita found it and took it back again. She was Catholic, and from Guatemala, and she must have thought she could shield me from finding out about Hitler, etc.

Book that changed your life:

Mario Vargas Llosa's 667-page doctoral thesis, published in 1971, Historia de un deicidio, in which he takes apart and studies Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude like a giant intricate clock, along with everything else written by and then known about the still fairly young GGM, as if he needed to make sense for himself of that book's genius. I read it in about 1984, when I couldn't have needed it more. I'd been living in Guatemala during the war years, doing freelance journalism in Central America while trying to start my own first novel. The parts about writing fiction in response to violence, terror, horrific injustice without becoming bogged down in sorrow, anger, political exigencies, etc., incorporating such darkness into a still somehow life-affirming vision, showed me the way forward, too. Vargas Llosa and Gabo had a legendary falling out, and the book has long been out of print, but I just read a new Spanish edition is coming out in July.

Favorite line from a book:

I think I'll go with this one, from Bolaños's The Savage Detectives: "The same thing happened to them that almost always happens to the best Latin American writers or the best of the writers born in the Fifties: the trinity of youth, love, and death was revealed to them, like an epiphany." That final clause hits home.

Five books you'll never part with:

Well, that old copy of Historia de un deicidio, badly in need of rebinding. Bolaño's 2666, in the gray Anagrama edition, which I read while on my honeymoon with my late wife, Aura. The New Black by Darian Leader, the book that most helped me through my own years of traumatic grief; densely marked-up, I drunkenly left it behind in a cab one night; bought a new copy, marked that one up nearly as much.

After my father died, my close friend Gonzalo gave me a signed copy of a boxed edition of his father's memoir, Vivir para contarla (Living to Tell the Tale in its English version). Gabo signed it: "con un abrazo de otró que también escribe" ("with a hug from another who also writes"). Two-volume edition of Nicanor Parra's Obras Completas, signed to Jovi and me by don Nicanor himself.

When I was doing research in Cuba on José Martífor The Divine Husband, I picked up some books nearly impossible to find anywhere else, including Destinatario Martí, a collection of letters written to Martí; the book was the work of an elderly electrician, Luis García Pascual, who'd devoted decades of his life to compiling it in his spare time, and we became friends; I brought an extra copy back and donated it to the New York Public Library.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Those transporting adult-versions of the Charlotte's Web experience are rarer than I wish. Most recent epic one: Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Quartet. But the one I'd most like to relive is War and Peace. I was in my early 20s, and I'd holed up in mid-winter in a boarding house in Oak Bluffs, Martha's Vineyard, intending to write a short story or two, but all I did was read that novel, and it so took me over that Natasha used to come to me in my dreams. That was Penguin's two-volume Rosemary Edmonds translation; this time I'll read the Pevear and Volokhonsky translation, already waiting on a shelf.

"Well friends, we did it. Today is our First Birthday. One year ago, in the middle of a Pandemic, we quietly opened for browsing--a far cry from the grand opening I had planned. In fact, on the surface, there wasn't much grand about that day at all. I remember sitting in the store full of questions. Would people be comfortable coming to shop with us? Should I even be opening? Was there something I was forgetting? Surely there was. I could go on and on about the list of worries that ran through my head.

"Well friends, we did it. Today is our First Birthday. One year ago, in the middle of a Pandemic, we quietly opened for browsing--a far cry from the grand opening I had planned. In fact, on the surface, there wasn't much grand about that day at all. I remember sitting in the store full of questions. Would people be comfortable coming to shop with us? Should I even be opening? Was there something I was forgetting? Surely there was. I could go on and on about the list of worries that ran through my head.

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.S1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

Richard Drake, owner of

Richard Drake, owner of

"

" River, Sing Out

River, Sing Out

Book you've bought for the cover:

Book you've bought for the cover: Pedro Mairal's The Woman from Uruguay follows a contemporary Argentine writer named Lucas for a single fateful Tuesday, as he travels from Buenos Aires to Montevideo and back again. Lucas narrates these events, with flashes forward and back in time, in a lengthy direct address to his wife, Catalina. "You told me I talked in my sleep. That's the first thing I remember." He is stumbling, if not entirely failing, as a writer, in debt to nearly everyone he knows, and fairly sure that Catalina is cheating on him. The purpose of the day trip to Uruguay is ostensibly to collect a significant sum of money in cash (advances on two books), which Lucas expects will change his fortunes. His hidden, secondary purpose is to visit the titular woman with whom Lucas has been captivated since they met at a writers' festival months earlier. He calls her Guerra--war--and is obsessed by their so-far-unconsummated affair.

Pedro Mairal's The Woman from Uruguay follows a contemporary Argentine writer named Lucas for a single fateful Tuesday, as he travels from Buenos Aires to Montevideo and back again. Lucas narrates these events, with flashes forward and back in time, in a lengthy direct address to his wife, Catalina. "You told me I talked in my sleep. That's the first thing I remember." He is stumbling, if not entirely failing, as a writer, in debt to nearly everyone he knows, and fairly sure that Catalina is cheating on him. The purpose of the day trip to Uruguay is ostensibly to collect a significant sum of money in cash (advances on two books), which Lucas expects will change his fortunes. His hidden, secondary purpose is to visit the titular woman with whom Lucas has been captivated since they met at a writers' festival months earlier. He calls her Guerra--war--and is obsessed by their so-far-unconsummated affair.

AmaZen Station

AmaZen Station

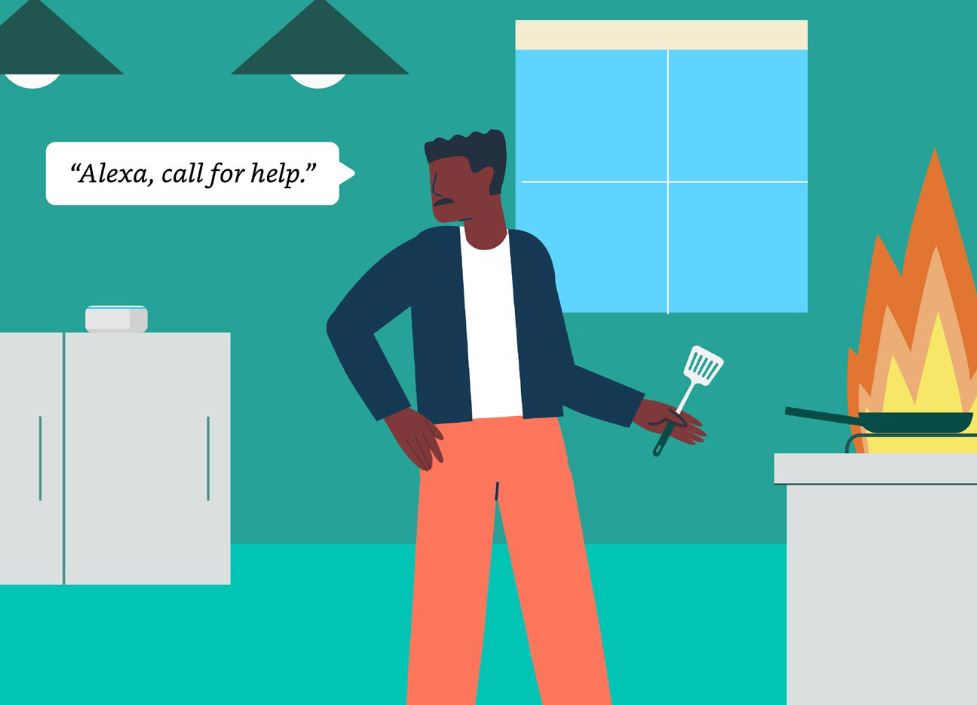

So here's a story. Call it a pitch to AmaMGM if you like. In a conference room at Blue Origin's mother ship building, Jeff Bezos, petting a white cat on his lap, sits at the head of a shiny table. The scene is futuristic--by late 1960s standards. His WorkingWell team reports that James Bond is now imprisoned in a customized ZenBooth pod, where he is being tortured by the incessant replaying--on multiple small screens and at high volume--of "guided meditations, positive affirmations, calming scenes with sounds, and more." There's no escape, or so it would seem. The locked door can only be opened by someone whose voice Alexa identifies through ASR (automatic speech recognition).

So here's a story. Call it a pitch to AmaMGM if you like. In a conference room at Blue Origin's mother ship building, Jeff Bezos, petting a white cat on his lap, sits at the head of a shiny table. The scene is futuristic--by late 1960s standards. His WorkingWell team reports that James Bond is now imprisoned in a customized ZenBooth pod, where he is being tortured by the incessant replaying--on multiple small screens and at high volume--of "guided meditations, positive affirmations, calming scenes with sounds, and more." There's no escape, or so it would seem. The locked door can only be opened by someone whose voice Alexa identifies through ASR (automatic speech recognition).