|

| Christopher M. Finan |

Christopher M. Finan, executive director of the National Coalition Against Censorship, is an authority on free speech and the First Amendment, and has written two books on the history of free speech in the U.S. Here he offers some thoughts on the importance of free speech for social change.

We are living through the worst book banning crisis in 40 years.

Librarians and teachers are under attack. Kids are also suffering as they are denied access to the books that can help them understand the world, themselves, even save their lives.

The only good thing about the current crisis is that it is a reminder of the critical role that free speech plays in making a better world.

We have certainly seen a lot of evidence on the other side. Free speech has made possible the spread of dangerous lies and hate speech on social media. But it is also true that free speech is advancing social justice.

Many police officers used excessive force on people protesting the murder of George Floyd. Without the protections of the First Amendment, including freedom of speech and freedom of the press, these protests, the largest in American history, might have become bloodbaths.

The half million women who marched in Washington to protest the inauguration of Donald Trump might have been denied a permit.

School officials could have locked the doors to stop kids from protesting gun violence following the murders at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

I have written two books about the history of free speech in the United States. The upcoming one, How Free Speech Saved Democracy: The Untold History of How the First Amendment Became an Essential Tool for Security Liberty and Social Justice (Steerforth Press, April 26), is a short introduction to the critical role that free speech has played in advancing equality.

It begins by explaining that free speech was not well understood when the First Amendment was adopted in 1791. Benjamin Franklin acknowledged that "few of us [had] any distinct Ideas of its Nature and Extent."

Over the next century and a half, reformers were frequently punished for advancing their radical ideas.

Abolitionist speakers were attacked at least 179 times during the 1830s and 1840s. When Theodore Dwight Weld visited Circleville, Ohio, a mob tried to drown out his words using sleigh bells, tin horns and drums. When that failed, they stoned the building where he was speaking. A brick knocked him senseless.

Frederick Douglass was struck down and almost killed during a riot in Pendleton, Indiana. He never recovered the full use of a hand that was broken during the fighting.

In 1848, Americans were shocked when a small group of men and women in Seneca Falls, New York, demanded full equality for women. Many of the leaders of the women's movement and their male supporters were arrested.

The passage of a federal obscenity law in 1873 gave Anthony Comstock, the leader of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, the power to persecute feminists, including Victoria Woodhull, the first woman to run for president, and Margaret Sanger, the advocate of reproductive rights.

Leaders of the labor movement were also censored. Broad injunctions barred workers from meeting to discuss collective action and engage in picketing and other forms of advocacy. Government troops and hired guns broke strikes, creating horrific violence.

During World War I, the federal government made a concerted effort to suppress criticism of America's participation in the war, convicting more than 1,000 and sentencing many to 20 years in prison, including Eugene V. Debs, the leader of the Socialist Party. After the war, the government arrested thousands of immigrants who were suspected Communists.

Things began to change with the founding of the American Civil Liberties Union in 1920, but progress was slow. The Supreme Court didn't issue its first decisions supporting free speech until 1931.

A free speech revolution began in the 1950s when the Supreme Court confronted massive resistance to its order to desegregate the nation's schools. State legislatures passed laws to cripple the civil rights movement. Police and state militia broke up demonstrations with blackjacks and fire hoses. The Ku Klux Klan killed civil rights workers. The Supreme Court responded by striking down every law that aimed to quell protest.

When L.B. Sullivan, the head of the police in Montgomery, Alabama, tried to silence the reporting of the New York Times by suing it for libel, the court created broad protection for both the press and individuals who criticize the government.

In the following years, the Supreme Court issued many decisions that protected free speech, including the right to protest the Vietnam war and to publish government secrets in the Pentagon Papers. It expanded artistic freedom by protecting books and movies with sexual content.

But the censors never gave up. In the early 1980s, the election of Ronald Reagan inspired conservatives, leading many activists to attack books by Judy Blume and other authors whose books helped kids deal with sex and other problems. Under pressure, school officials folded, removing the books that were causing them problems.

Today's censors are still angry about sexual content, but they have added new targets. Legislatures are passing vague laws to regulate teaching about the role of racism in American history and to limit discussion of sexual identity. The number of book challenges has soared and may soon exceed the last peak.

This wave of censorship will be no more successful than the last one. Right now conservatives have the upper hand, but defenders of free speech are beginning to rally. These are the same people who have stepped forward in the past--students, parents, teachers, librarians, authors, publishers and booksellers.

They do not quarrel with parents who want to choose an alternative to a book they find offensive. But they believe strongly that no parent should decide what other people's children should read.

They have confidence in the professionalism of the teachers and librarians who choose books for the classroom and library. They support strong policies that require challenged books to be read in their entirety by committees that include both a professional and a parent.

While they understand that the relationship between social change and free expression is complex, they are confident that the societies that encourage freedom are the ones that flourish.

Free speech is not an obstacle to change. It is the way we address our problems.

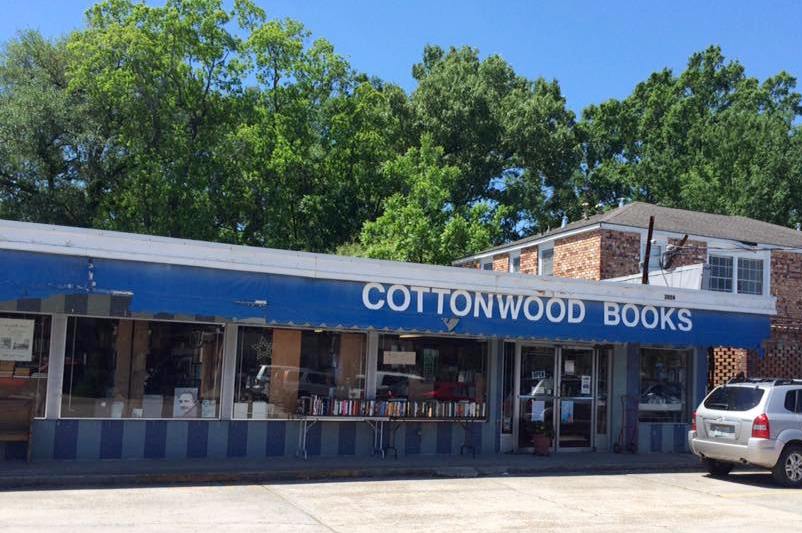

Sonny Cranch, a longtime customer of Cottonwood Books in Baton Rouge, La., has teamed with other community members to launch a GoFundMe campaign to help save the bookstore, which was slated to close after owner Danny Plaisance could not find a buyer. Per the LSU Reveille, Cranch plans to create a nonprofit company called the Cottonwood Project to run the bookstore, and he is looking to raise $150,000 to establish it.

Sonny Cranch, a longtime customer of Cottonwood Books in Baton Rouge, La., has teamed with other community members to launch a GoFundMe campaign to help save the bookstore, which was slated to close after owner Danny Plaisance could not find a buyer. Per the LSU Reveille, Cranch plans to create a nonprofit company called the Cottonwood Project to run the bookstore, and he is looking to raise $150,000 to establish it.

SHELFAWARENESS.0213.S4.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

Books-A-Million will

Books-A-Million will

Results from the Publishers Association's

Results from the Publishers Association's  The Australian Booksellers Association has

The Australian Booksellers Association has SHELFAWARENESS.0213.T3.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

Comedian Charlie Berens (center), author of The Midwest Survival Guide: How We Talk, Love, Work, Drink, and Eat... Everything with Ranch (HarperCollins), with

Comedian Charlie Berens (center), author of The Midwest Survival Guide: How We Talk, Love, Work, Drink, and Eat... Everything with Ranch (HarperCollins), with

Two Storm Wood: A Novel

Two Storm Wood: A Novel At last night's

At last night's  Musicians Ben Please and Beth Porter were among the nominees for an Oscar this year. Also known as the

Musicians Ben Please and Beth Porter were among the nominees for an Oscar this year. Also known as the  The Perfect Golden Circle is a thrilling introduction to a British literary star and a moving meditation on history, trauma and the urge to create. Set in 1989, the novel takes place almost exclusively in the fields of rural England, where protagonists Calvert and Redbone use boards and rope to create massive, complex crop circles. Benjamin Myers (The Offing) maintains a tight focus on his two principal characters, societal outcasts with an intense, almost theological devotion to their craft. Perhaps his most impressive achievement is how, in chapters dedicated to the construction of a particular crop circle, Myers manages to stretch his focus far beyond the confines of the field, to encompass the social and political conflicts roiling the rest of the country.

The Perfect Golden Circle is a thrilling introduction to a British literary star and a moving meditation on history, trauma and the urge to create. Set in 1989, the novel takes place almost exclusively in the fields of rural England, where protagonists Calvert and Redbone use boards and rope to create massive, complex crop circles. Benjamin Myers (The Offing) maintains a tight focus on his two principal characters, societal outcasts with an intense, almost theological devotion to their craft. Perhaps his most impressive achievement is how, in chapters dedicated to the construction of a particular crop circle, Myers manages to stretch his focus far beyond the confines of the field, to encompass the social and political conflicts roiling the rest of the country.