Notes from Frankfurt: Mohsin Hamid on Books As an Antidote to 'a Period of Darkness'

The guest speaker at the opening press conference of the Frankfurt Book Fair was Mohsin Hamid, author most recently of The Last White Man, who presented a simultaneously dispiriting and hopeful outline of global civilization, which, he said, "is entering what seems like a period of darkness."

The guest speaker at the opening press conference of the Frankfurt Book Fair was Mohsin Hamid, author most recently of The Last White Man, who presented a simultaneously dispiriting and hopeful outline of global civilization, which, he said, "is entering what seems like a period of darkness."

He recalled feeling as a child that "the world would keep getting better," and that for many decades he remained positive as he lived variously in the U.S., U.K. and Pakistan. Among the achievements he cited: people landing on the moon, the end of the Pakistani dictatorship, the end of the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, the fall of the Berlin Wall, growing economic prosperity, the tech revolution, including the introduction of e-mail and the Internet.

|

|

| Mohsin Hamid speaking at Frankfurt yesterday. | |

And after the turn of the century, despite "wars and genocides" and "an emerging sense that fossil fuels might be a problem," even through the election of Donald Trump, Brexit, Pakistan's rolling back of civil liberties and press freedom, and "the shockingly rapid retreat of glaciers in the Himalayas," there was nothing that "technology and democracy and the market could not eventually solve."

Not until "sometime around 2020, as the Covid pandemic came, and it was every country for itself, and borders closed, and there were no flights in or out of Pakistan for many weeks, and schools and offices were shut, and driving around was restricted, and the stars came out again at night, because the pollution had receded, and bees and butterflies and birds were everywhere, and my city of twelve million people was quiet, I could no longer force myself to believe, and I found that my faith in inevitable improvement was gone." Instead he said, he had feelings "of confusion and of loss," feelings that were shared by many of his friends.

He also noted that younger people have told him they never believed things would get better. "For them it seemed instead that it was getting worse. Their parents might have grown up in a less troubled era. But for their own generation the task was just to do the best they could in the face of mounting uncertainty and anxiety."

At first, he thought he had been positive for so long because there was always "a clear formula for progress: the formula of democracy plus science plus economics." But then he came to believe that the basis of his optimism was simply "the irresistibility of cooperation." But currently cooperation is not happening, and "without cooperation we cannot tackle challenges like climate change, inequality, migration, disease, weapons of mass destruction. And yet we seem determined to cooperate less and less. Our world is fracturing into mutually suspicious nations and clans and tribes."

This new lack of cooperation and connection is more dangerous than at any other period in human history because "we are vastly more powerful. The harm we can do to one another, and to our planet, is unprecedented in its scope and complexity."

He then said that "the future of humanity is shaped by the stories we choose to believe in." While TV and film offer passive experiences to their "viewers," books are different. "When we open a book, we encounter letters and punctuation marks against a white field. It is we who then create in our imagination people and places and sights and sounds. The reader of a book is not a viewer. Readers are creators, inspired by the source code of the text they hold in their hands."

Reading literature involves something like the kind of imaginative play most children engage in but that adults avoid. "The very idea [of playing] seems, somehow, to embarrass us. Except when we are alone, that is, and we pick up a book, and we give ourselves permission to play in our imagination with another person, a person we do not know and who is not there, a writer."

Novels are crucial to the future of the planet, Hamid said, "not only because they tell us stories of people who are different from us, and allow us to empathize, and encourage us to blur the boundaries between one group and another. No, novels are also important because of their form, because writing and reading a book is itself a profound and hopeful act of cooperation. Novels emanate from our desire for the fertility that arises when we remember that it is we who imagine ourselves and our world into existence, that we are jointly the authors of what we call reality, and that we can choose to author differently. In a world that seems to be entering into a time of darkness, novels are embers that we cup in our hands, embers of potential."

He added that "reading a book is almost like meditating... if you haven't read a book in a while, you think it's hard because you keep thinking about something else." The technology of the book means "you can't click on anything. You can't go anywhere else." Most other technology is harmful because it attempts to monetize users' attention, and it gets attention most effectively by projecting and portraying threats. As a result, people are "tremendously distracted" and "the continuous onslaught of threats" creates huge amounts of anxiety and leaves people "paralyzed and hateful and polarized."

On the other hand, "Books are quite different because they allow us to re-engage with sustained attention and to be directing our own attention."

Although he admitted he didn't know how it could be done, Hamid hopes that technology can be changed to "restore to readers--to human beings--an ability to be the authors of where they direct their attention." People should stop allowing their attention to be directed "for us, from one threat to the next, from one distraction to the next." Technology should be changed from something "authored on us to something we can author with," something to make us "better readers," to "make us more focused." And thus people can remake the world. --John Mutter

Felicia Frazier, senior v-p, children's and education sales, at Penguin Random House, is leaving at the end of the year, Jaci Updike, president, sales, Penguin Random House U.S., announced in a memo to staff. Frazier joined Random House as a national accounts manager in 1994 and has held a variety of management positions there, at Penguin, and then at Penguin Random House.

Felicia Frazier, senior v-p, children's and education sales, at Penguin Random House, is leaving at the end of the year, Jaci Updike, president, sales, Penguin Random House U.S., announced in a memo to staff. Frazier joined Random House as a national accounts manager in 1994 and has held a variety of management positions there, at Penguin, and then at Penguin Random House.

National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist Marianne Wiggins stopped by

National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist Marianne Wiggins stopped by

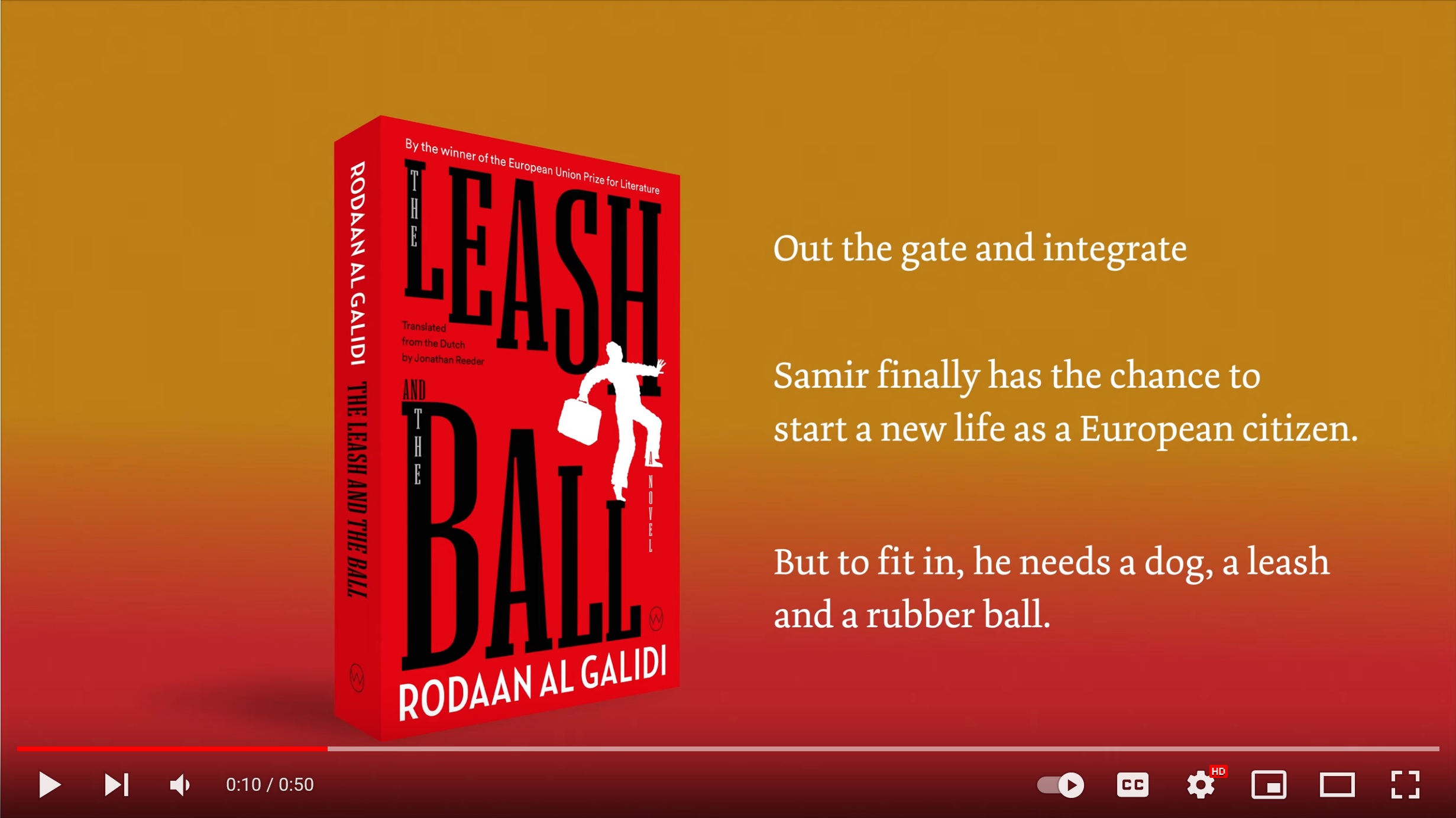

The Leash and the Ball

The Leash and the Ball

Book you're an evangelist for:

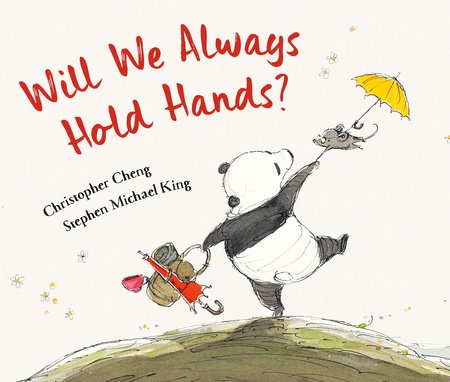

Book you're an evangelist for: For many adult readers, Will We Always Hold Hands? will awaken a comparison with Margaret Wise Brown's The Runaway Bunny. Both picture books are powered by a dialogue between two animals, one with a barrage of questions designed to establish the extent of the other's devotion. But with Will We Always Hold Hands?, author Christopher Cheng (One Tree) and illustrator Stephen Michael King (You: A Story of Love and Friendship) introduce a daring degree of complexity by acknowledging that there are limits to the power of unconditional love.

For many adult readers, Will We Always Hold Hands? will awaken a comparison with Margaret Wise Brown's The Runaway Bunny. Both picture books are powered by a dialogue between two animals, one with a barrage of questions designed to establish the extent of the other's devotion. But with Will We Always Hold Hands?, author Christopher Cheng (One Tree) and illustrator Stephen Michael King (You: A Story of Love and Friendship) introduce a daring degree of complexity by acknowledging that there are limits to the power of unconditional love.