_Jessica_Baran.jpg) |

| photo: Jessica Baran |

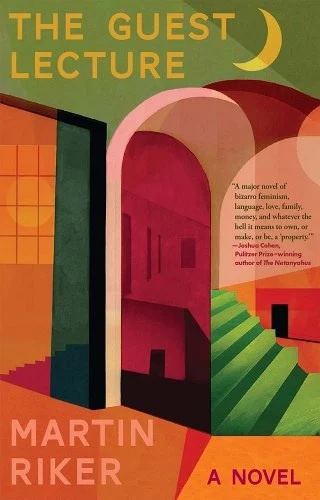

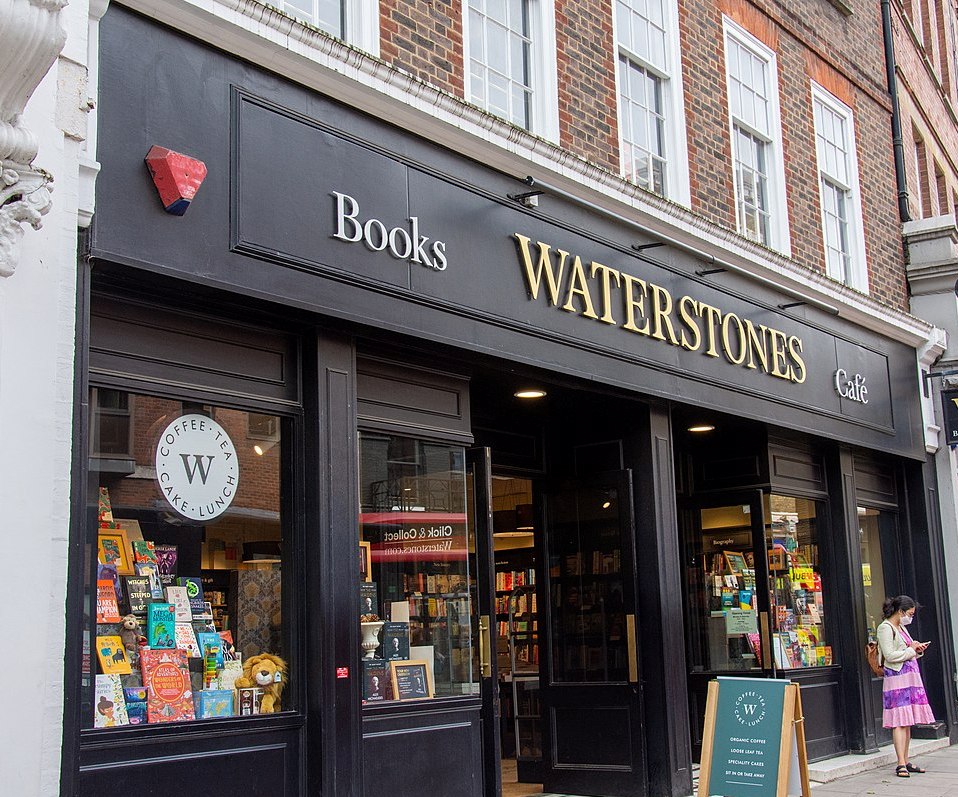

Martin Riker's second novel is The Guest Lecture (Black Cat/Grove Press, January 24, 2023), which follows a feminist economist through one fantastical sleepless night. Riker is co-founder and publisher of the feminist press Dorothy, a publishing project, and the author of Samuel Johnson's Eternal Return. As a critic, he has written for the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Paris Review Daily, TLS and the London Review of Books.

Handsell readers your book in 25 words or less:

The story of an insomniac economist using her imagination to battle the encroaching darkness. My agent adds, "Like if Beckett wrote a book for moms."

On your nightstand now:

An ARC of a novel I'm reviewing. I'm halfway through right now, so the front half of the ARC is a bloated monster of Post-it notes and dog-eared pages, while the latter half still just looks like a book. Also a Pirandello novel, Elizabeth Sewell's The Orphic Voice, Jeff Deutsch's In Praise of Good Bookstores and a scholarly book by Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost about the history of the Atari 2600.

Favorite book when you were a child:

I wasn't much of a reader as a kid. I became a reader in my 20s, which is maybe why I didn't publish my first novel until my 40s. I do have a memory of spending a lot of time with Choose Your Own Adventure books. But the children's authors most important to me are ones I came to as an adult, notably Lewis Carroll, whose spirit runs through my new novel. Carroll shares some DNA with Choose Your Own Adventure, I think. Books that offer a playful and active experience of reading have always been my favorites.

Your top five authors:

All of the authors I publish through Dorothy. My wife and I run a publishing house that brings out two books per year of surprising and wonderful fiction or near-fiction by women. As publisher of these books, I avoid stating favorites, but taken together the authors on Dorothy's list have had an incalculable impact on my life and my reading.

Denis Diderot. Diderot was my kind of polymathic, playful, all-over-the-place (but still shrewd, elegant) writer. His books are so different from each other, not just in premise but in spirit. He made a very large and seminal encyclopedia [Encyclopédie]; according to James Wood, he basically invented (in Rameau's Nephew) the self-warring character ("characterological relativity"), inaugurating the psychological novel as practiced by Dostoyevski on down; and he also wrote one of the funniest books of all time, Jacques the Fatalist. There is a brilliant but sadly out-of-print translation of his This Is Not a Story and Other Stories that someone needs to reissue.

Nikolai Gogol. Dead Souls--what a book! But I also sometimes teach three of his stories together: "The Nose," "The Overcoat" and "Diary of a Madman." These are all comedies about clerks and satires about class and aspiration, but each one navigates the space between absurdity and reality in a totally different way.

Fran Ross. The reason Fran Ross is not at the top of this list is because, tragically, she published only one book and because I write more about her below.

François Rabelais. I guess I like old, funny books? Or I like hilarious, uncontainable books that never lose their force and genius regardless of age. Gargantua and Pantagruel is a wellspring of so much literary joy. "Revere the cheese-shaped brain that feeds you this noble flummery."

Book you've faked reading:

Faked or just skimmed a lot? I can't think of anything I've actually faked, but I can think of a whole lot of books I've skimmed. As a younger reader, I was a completist: I picked certain authors (Beckett, Flaubert) and read every word. Now I suppose I am something less than that.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Fran Ross's Oreo is my favorite book. The freedom and excitement that I experience every time I read it is the purest expression I have ever found of why books matter to me.

Book you've bought for the cover:

There was one, about 25 years ago. I was working as a musician on a cruise ship, and I went to a bookshop in San Juan and picked up a book because the cover was weird--faux wood grain, like a box. A book-shaped box. I don't think the book was very good.

Book you hid from your parents:

Ha! My parents wished I was secretly reading books.

Book that changed your life:

Life: A User's Manual by Georges Perec. I had been reading formally inventive fiction for some time before I discovered Perec, but his particular combination of playfulness with serious intelligence, or restraint with unbridled invention, or generosity with an unflinching eye--all the unique ways he put art and life in conversation with one another--was a revelation to me. In his novel Life: A User's Manual, he takes the reader room by room through a Parisian apartment building, carefully describing each apartment before placing inside it the stories of the people who lived there. It's a simple move but monumental in its effect. Readers of my new novel might notice that I borrowed this idea--describing a space before placing a story inside it--though what I did with it is very different.

Favorite line from a book:

From Bill Johnston's translation of Witold Gombrowicz's Bacacay: "It is with great emotion that I run toward you, my childhood!"

Five books you'll never part with:

Aside from the books I've already mentioned? Samuel Beckett's Stories and Texts for Nothing. Jaimy Gordon's Bogeywoman. Danielle Dutton's Prairie, Dresses, Art, Other (this is my wife's next book, forthcoming in 2024). Ishmael Reed's Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down. Elizabeth Sewell's The Field of Nonsense.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

There is a type of book that is so singular and perfect, so entirely self-contained and unexpected, that reading it for the first time is particularly special, since it appears fully formed out of nowhere and remakes the world. Of course, this effect can't be repeated, since once you've read it, the world has already been remade. Books in this category for me include Tove Jansson's The Summer Book, Édouard Levé's Suicide, Nathalie Léger's The White Dress, Cristina Rivera Garza's The Taiga Syndrome, Pamela Lu's Pamela: A Novel, Roland Barthes's Camera Lucida and Georges Perec's W, or the Memory of Childhood.

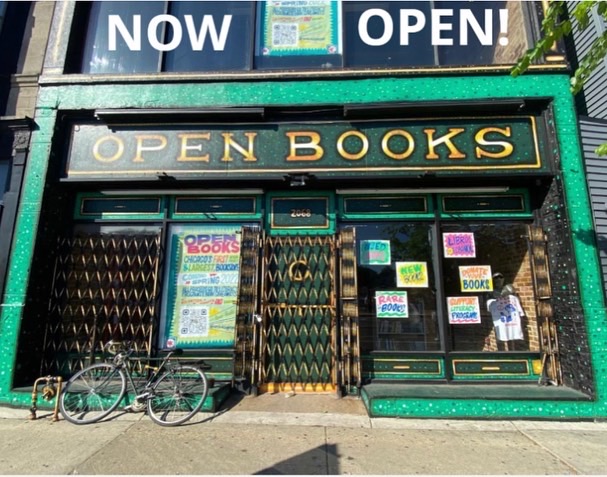

Open Books, a literacy nonprofit that runs full-service bookstores featuring donated, remaindered and new books, launched its third community bookshop earlier this week, at 2068 N. Milwaukee Ave. in Chicago's Logan Square neighborhood. Open Books also operates stores in Pilsen and in the West Loop.

Open Books, a literacy nonprofit that runs full-service bookstores featuring donated, remaindered and new books, launched its third community bookshop earlier this week, at 2068 N. Milwaukee Ave. in Chicago's Logan Square neighborhood. Open Books also operates stores in Pilsen and in the West Loop.

The Gerald R. Ford International Airport, in partnership with Hudson, has started construction on

The Gerald R. Ford International Airport, in partnership with Hudson, has started construction on

The

The

"Today only!

"Today only!  "Come find your next favorite winter read!"

"Come find your next favorite winter read!" _Jessica_Baran.jpg)

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for: At one point in Rebecca Makkai's I Have Some Questions for You, in which a clutch of New England prep school graduates reunite 20-plus years later under dark circumstances, one of them texts a question about their gathering: "Is it more like THE BIG CHILL, or the second half of IT?" Makkai's dauntless and enthralling fourth novel, as far as likenesses go, is worthy of comparison with Jean Hanff Korelitz's The Plot--another shrewd, campus-set literary thriller--and the first season of the standard-bearing did-he-or-didn't-he? podcast Serial.

At one point in Rebecca Makkai's I Have Some Questions for You, in which a clutch of New England prep school graduates reunite 20-plus years later under dark circumstances, one of them texts a question about their gathering: "Is it more like THE BIG CHILL, or the second half of IT?" Makkai's dauntless and enthralling fourth novel, as far as likenesses go, is worthy of comparison with Jean Hanff Korelitz's The Plot--another shrewd, campus-set literary thriller--and the first season of the standard-bearing did-he-or-didn't-he? podcast Serial.

Now there's a disturbance in the audiobook force field. Earlier this month, Apple "

Now there's a disturbance in the audiobook force field. Earlier this month, Apple " "Voice is both story and backstory. Voice is the entry point for narrative," actress, screenwriter and director

"Voice is both story and backstory. Voice is the entry point for narrative," actress, screenwriter and director  Currently I'm listening to Beata Pozniak read--possess, really--the audiobook version of

Currently I'm listening to Beata Pozniak read--possess, really--the audiobook version of