Wi2023: Book Banning: Stores, Authors and Communities: What Can We Do?

"What was once an occasional distraction and disruption has increasingly become a daily occurrence," said Ray Daniels, ABA's chief communications officer, at the outset of the Winter Institute session "Book Banning: Stores, Authors and Communities: What Can We Do?" He went on describe how book bans affect bookstores, authors and communities, with challenges in stores turning into the quiet censorship of books turned spine-out, harassment of staff, social troubles and more. He then asked the panelists how they've addressed this issue in their own communities.

"What was once an occasional distraction and disruption has increasingly become a daily occurrence," said Ray Daniels, ABA's chief communications officer, at the outset of the Winter Institute session "Book Banning: Stores, Authors and Communities: What Can We Do?" He went on describe how book bans affect bookstores, authors and communities, with challenges in stores turning into the quiet censorship of books turned spine-out, harassment of staff, social troubles and more. He then asked the panelists how they've addressed this issue in their own communities.

Heather Hall comes from Green Feather Book Company in Norman, Okla., a town where a teacher lost her job as a direct result of sharing the Brooklyn Public Library's Books Unbanned QR code. "Immediately parents came together in outrage" in response to the firing, said Hall, who began making buttons in her store with the QR code on them. Her middle schoolers then went to class wearing them and encouraged their peers to scan the code.

|

|

| (l.-r.) Heather Hall, Ray Daniels, Laura DeLaney, Maia Kobabe, Kendrick Washington | |

Maia Kobabe is the author of Gender Queer, the number-one banned book in the United States in 2021, "and I will be very unsurprised if it is number one of 2022 as well," Kobabe said. "But if it wasn't my book, it would be another." Kobabe identified the topics that are being targeted as gender, sexuality, history of race in America, sex ed, abortion, immigration and students rights. "What I've come to learn is that a book being challenged doesn't really hurt the book or the author, but it hurts the communities where those challenges are being placed."

From the state of Idaho, Laura DeLaney of Rediscovered Books in Caldwell is no stranger to book bans. "But it really kicked into high gear in summer of 2022," she said, when the neighboring Nampa school district banned 24 books, "without following any procedures whatsoever." Her store immediately made a statement against this and raised money across the country to give away more than 1,500 books to students, parents, and community members.

"Books saved my life, as a young Black kid who was born into poverty," said Kendrick Washington, policy advocacy director of the Seattle ACLU. He reminded the audience that book bans are nothing new, giving examples like Ulysses and Howl, then identifying the twin historical causes as the patriarchy and white supremacy: lack of books has been used to hold people down and deny progress, from the roots of slavery to now wanting to deny LGBTQ youth an opportunity to find community where they may not be able to find it in their own neighborhoods.

DeLaney observed that books contribute to a full and dynamic society, instead of making subjects like queerness an "X-rated issue." The cost of book bans, Kobabe added, restricts access for those who need the books most, further marginalizing those already marginalized. "We shouldn't have to have a lawsuit in every single school district just to have books in schools and libraries," Kobabe said.

Hall suggested that areas like hers are testing grounds for further legislative reach, and DeLaney elaborated on ways that Idaho House Bill 139, which threatens librarians and teachers with $10,000 lawsuits if "damaging" materials are accessed by minors, could have a chilling effect on collections and access more broadly. Washington said the point of legislation like this is to weaponize ignorance against those perceived as other. "The beauty of the book ban," Daniels added, "is to erase the history we're supposed to learn from."

Turning to solutions, DeLaney gave the example of Rediscovered's Read Freely Project, which endeavors to promote through giveaways those minority voices that have been banned. Hall returned to the guerilla QR-button effort she spearheaded and championed the power of small acts of support that individuals can make to show their communities support. Kobabe has noticed that Banned Book store displays are no longer seasonal in many places, keeping attention on this issue year-round. Pay-it-forward programs, as well, can help cover the costs for young readers who may not have resources to buy books otherwise. DeLaney also suggested that bookstores can join a local library association, affordable memberships that can help block legislation before a ban can take place.

Washington encouraged booksellers who feel endangered to reach out to the ACLU, and added that while school districts have great authority to remove books, they are not allowed to discriminate. The ACLU can help a community understand their options, but said, "When that community pulls itself together and makes a stink, that's where the real work is done."

But with many book bans and challenges being done quietly, secretly even, Kobabe noted that a firm library collections policy being set in place preemptively can put the onus on the challenger to prove a book's potential for harm.

In closing, Hall said, "It's dangerous to be political when you own a business," but everyone in attendance seemed to be in agreement that the people who want to ban books aren't dedicated readers themselves, so they are not any store's regular customer. DeLaney approaches those who come in looking for a fight kindly but firmly, and Hall has found that bans have served to alert other people in the community who are ready to take up the cause. --Dave Wheeler

IPC.0204.S3.INDIEPRESSMONTHCONTEST.gif)

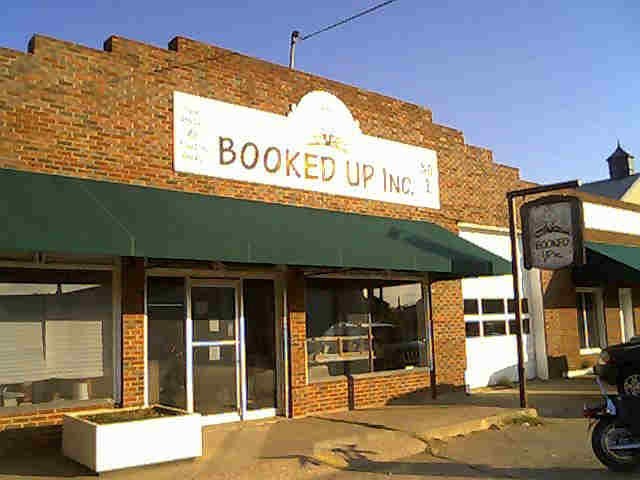

In one of the more unlikely book-related pairings, Chip Gaines, the star, with his wife, Joanna Gaines, of the cable home improvement show Fixer Upper, the Magnolia Network and head of a lifestyle/entertainment empire centered in Waco, Texas, has bought Booked Up, the bookstore founded by the late Larry McMurtry, author of Lonesome Dove, The Last Picture Show, Terms of Endearment and other modern classics.

In one of the more unlikely book-related pairings, Chip Gaines, the star, with his wife, Joanna Gaines, of the cable home improvement show Fixer Upper, the Magnolia Network and head of a lifestyle/entertainment empire centered in Waco, Texas, has bought Booked Up, the bookstore founded by the late Larry McMurtry, author of Lonesome Dove, The Last Picture Show, Terms of Endearment and other modern classics.

IPC.0211.T4.INDIEPRESSMONTH.gif)

Congratulations to

Congratulations to  Something Wild

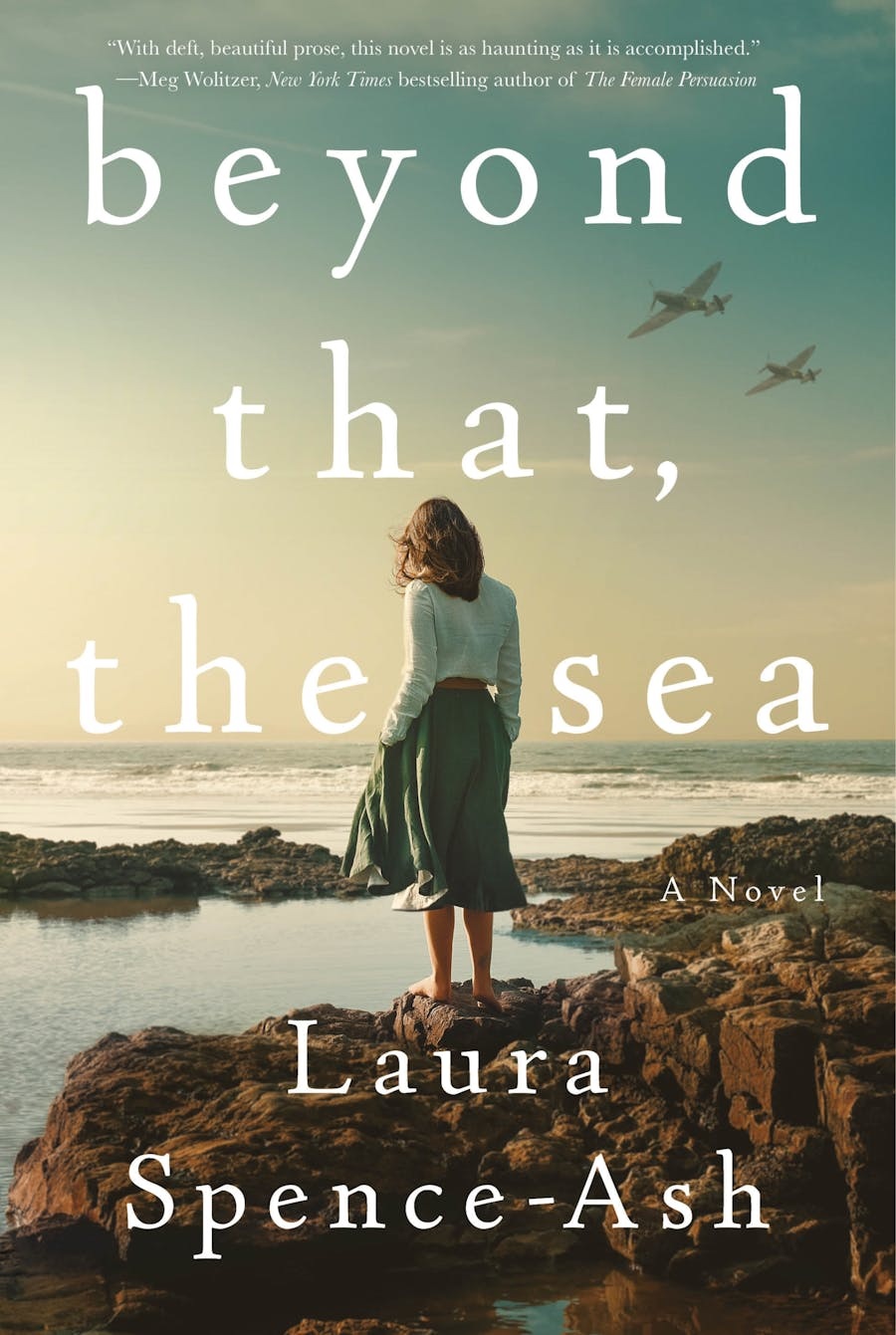

Something Wild Laura Spence-Ash's debut novel, Beyond That, the Sea, weaves a tapestry of intimate relationships that span the Atlantic in the decades after World War II. At the novel's center is Beatrix Thompson, whose parents, Millie and Reg, make the heart-wrenching decision to send her, at age 11, across the ocean to escape the Blitz in London. Bea lands with a well-off family, the Gregorys, who live near Boston and spend summers on a private island in Maine. She becomes close to the two boys, William and Gerald, and her bond with them and their parents--deep and complicated--will endure.

Laura Spence-Ash's debut novel, Beyond That, the Sea, weaves a tapestry of intimate relationships that span the Atlantic in the decades after World War II. At the novel's center is Beatrix Thompson, whose parents, Millie and Reg, make the heart-wrenching decision to send her, at age 11, across the ocean to escape the Blitz in London. Bea lands with a well-off family, the Gregorys, who live near Boston and spend summers on a private island in Maine. She becomes close to the two boys, William and Gerald, and her bond with them and their parents--deep and complicated--will endure.