|

| Lanora Jennings |

Sales rep and former bookseller Lanora Jennings says that if the book world wants to continue to lower the barriers to entry for a diverse group of new booksellers, we need to go to them, instead of assuming they can come to us. Just as they are reimagining business models, we need to reimagine how to help them learn how to run their businesses.

In 1993, independent bookselling was facing a major crisis. Chuck Robinson, then ABA president and owner of Village Books, Bellingham, Wash., said that there was "concern over the future of bookselling with the growth of mega-stores and now electronic publishing.... Selling books is like farming; what's being threatened is not just a job, but a life."

I was called to the life of bookselling 30 years ago. As a young bookseller, I was fortunate to have some incredible mentors, including Carla Cohen, co-founder of Politics & Prose, Washington, D.C., and David Schwartz of the Harry W. Schwartz bookstores in Milwaukee, Wis. They invested in me. I was brought to the trade shows and encouraged to attend the education sessions. Knowing I wanted to open a store of my own, Carla rotated me through every position in the store, from receiver to buyer, so I could gain the knowledge I needed. The team at Harry W. Schwartz gave me the opportunity to manage and operate two of their locations, without any previous experience other than being part of their bookselling family. I earned my Master's in Bookselling between the stacks, in real time.

Today, I am a publisher sales representative. This January, I was done with attempting traditional sales calls over Zoom. What used to be a 90-minute conversation had dwindled down to a 20-minute one-dimensional connection. It was time to get back on the road. I began planning a normal travel season--except there would be nothing normal about it. More than 50 new stores have opened in my territory in the past three years. I had never met the owners, nor seen their stores. My established stores were so adept at working virtually we no longer needed a traditional sales call. The relationships we established in person led to a level of trust and communication that was not impeded in the virtual space.

Prior to 2020, traveling to smaller stores more than an hour from a major account did not justify the cost to acquire a $300 order. Yet, bookselling is grounded in face-to-face meetings. Whether at a rep picks session, over drinks at a convention, or personal visits to the stores, this business is conducted through our relationships. Even if I did not travel to the store, I was able to connect with booksellers at the trade shows. These new stores had been deprived of this opportunity, opening in a time of total isolation.

I flipped my focus to these new stores. I visited 66 bookstores, 32 of which had opened in the past three years. These new booksellers have created some amazing spaces. Kismet Books, located in a charming historic building, has become a safe space for local LGTBQ+ teens to hang out in rural Wisconsin. In Detroit, an unassuming brick building with no display windows is home to 27th Letter Books. The store feels like a living room in a posh studio apartment: inviting, comfortable, and filled with warm Midwestern hospitality. The operation is Black-owned, woman-owned, and Filipino-owned. One co-owner wrote that they wanted a store that "had something for everyone, a community where everyone is accepted no matter how strange." The industry has rejoiced at this influx of new bookstores. However, it may be too early to celebrate.

In my conversations with my new booksellers, I became concerned about their long-term viability. In one store, my visit entirely consisted of showing the manager how to use iPage. In another, I gave a crash course in using Edelweiss. Most of these stores told me they source 100% of their inventory from a wholesaler--not a sustainable practice. Booksellers had various reasons for not ordering directly from publishers: multiple direct orders took too much time; the learning curve was high; they didn't know how to open an account; they weren't using Edelweiss. With little or no previous bookselling experience, these booksellers were unaware of the resources available to them, or if they did, they were unable to take advantage of them. With only one full-time employee--themselves--few could afford the time and cost to attend the educational sessions offered at the trade shows. Scholarships are not an option if you have to close the store and lose a few days of business.

Most independent bookstores have been in predominantly white neighborhoods with a matching staff. Our industry has been slow to recognize the cultural and financial barriers of entry to bookselling. These new owners lacked many of the advantages I had as a young bookseller. Unlike many of my peers, they don't have an alternative source of income to support getting experience in a bookstore. Getting a job in a bookstore located in a community that doesn't reflect their identity has both emotional and logistical barriers. Working in a bookstore doesn't just teach you how to shelve books and run a register. Bookselling has its own unique culture, norms, and business practices that are learned through the connection with the book trade community at large. The exchange of ideas when we gather has made us collectively better at running events, managing our time, and much more. In the past, these connections are what educated and encouraged booksellers become the next generation of owners.

The new booksellers are creating a new kind of space--an ideal bookstore--that is welcoming and reflective of their communities. They are inspiring the rest of us to finally have important conversations on diversity and representation, offering a living wage, reimagining our business models. Yet, we can't forget that the ideal bookstore is still vulnerable to poor inventory management, lack of capital, or insufficient training.

For over a century, the book trade has recognized the value in educating the next generation of booksellers. The American Booksellers Association published the first Manual of Bookselling in 1921. Since then, a core component of the mission of the ABA and the regional booksellers associations has been education. Aspiring booksellers can attend bookselling schools and workshops. I'm not suggesting that education isn't available. I'm suggesting that these opportunities are often unattainable for many. We should also be reimagining our education models: start a one-on-one, low-cost mentoring program; provide in-person or virtual emergency "house calls"; provide scholarships for a veteran bookseller to spend time in their stores. Without easy access to the traditional methods of learning the trade, these stores are having to reinvent the codex.

As many publishers are looking at their dismal fiscal year, they are seeing one bright spot: an increase in sales through the independent bookstore market--something booksellers have been fighting for since the early '90s. This growth in market share is partly due to the education, collaboration, and community outreach initiatives that grew in response to that crisis. What will happen to these new stores if those answering the call of bookselling are unable to access the traditional spaces of education and collaboration? If they can't come to us, we need to go to them. It is time to get on the road.

Lanora Jennings is the Midwest sales representative for both Princeton University Press and Yale University Press. She is also researching and writing a book on the history of independent bookstores in America. Follow her on Instagram and Threads @bookstore_chronicles

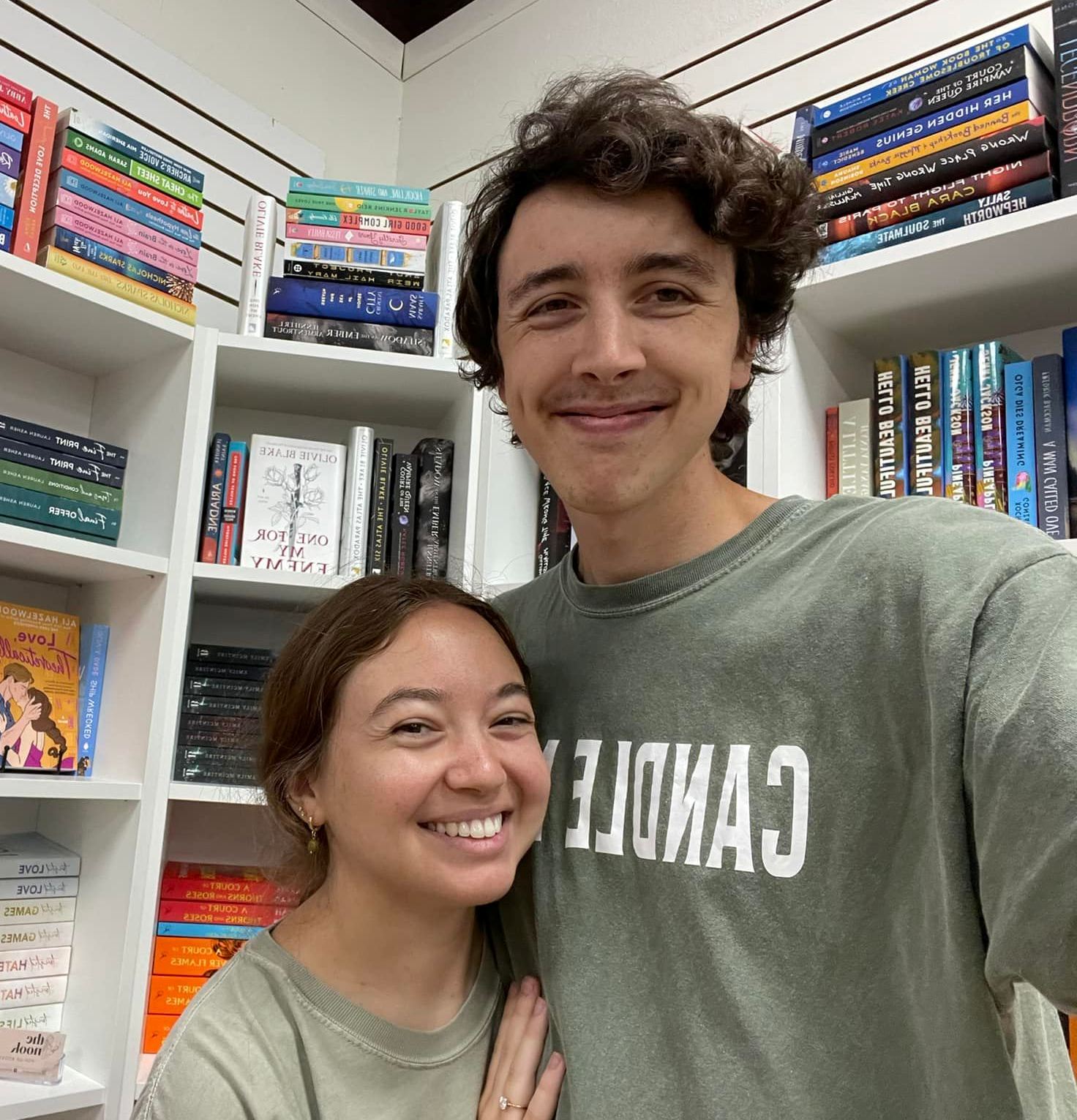

Black Cat Books & Oddities, with a family-friendly "eccentric Victorian vibe," officially opened yesterday in the historic South Town district of Medina, Ohio, near Cleveland. The owners are Max Frazier and Alicia Hoisington Frazier, who live in Medina with their two children.

Black Cat Books & Oddities, with a family-friendly "eccentric Victorian vibe," officially opened yesterday in the historic South Town district of Medina, Ohio, near Cleveland. The owners are Max Frazier and Alicia Hoisington Frazier, who live in Medina with their two children.

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

Author Wickliffe W. Walker received a diagnosis that kept him from attending New Voices New Rooms in Arlington, Va., last week, where he was scheduled to appear at the Indie Press Author Reception and sign copies of his forthcoming Torrents As Yet Unknown: Daring Whitewater Ventures into the World's Great River Gorges (Steerforth Press). So dozens of booksellers did a reverse author signing to honor Walker--adding their store names and hometowns to a life preserver shirt brought to the show by Steerforth sales and marketing director David Goldberg. BINC's Pam French got wind of the outpouring of support and pointed out that this is what booksellers do: "They show up and show support." Pictured: SIBA executive director Linda-Marie Barrett (l.) and BINC executive director Pam French.

Author Wickliffe W. Walker received a diagnosis that kept him from attending New Voices New Rooms in Arlington, Va., last week, where he was scheduled to appear at the Indie Press Author Reception and sign copies of his forthcoming Torrents As Yet Unknown: Daring Whitewater Ventures into the World's Great River Gorges (Steerforth Press). So dozens of booksellers did a reverse author signing to honor Walker--adding their store names and hometowns to a life preserver shirt brought to the show by Steerforth sales and marketing director David Goldberg. BINC's Pam French got wind of the outpouring of support and pointed out that this is what booksellers do: "They show up and show support." Pictured: SIBA executive director Linda-Marie Barrett (l.) and BINC executive director Pam French.

W.W. Norton will handle print and digital distribution in the U.S. and some international markets for The Experiment Publishing, effective January 1.

W.W. Norton will handle print and digital distribution in the U.S. and some international markets for The Experiment Publishing, effective January 1. Captain Clementine: Secret of the Star

Captain Clementine: Secret of the Star The Last Language by Jennifer duBois (A Partial History of Lost Causes; Cartwheel;

The Last Language by Jennifer duBois (A Partial History of Lost Causes; Cartwheel;